Nobody expected “the girl in the show” to walk off the stage as a feminist icon. “Love, Gilda” follows the life and laughs of comedian Gilda Radner, the first female cast member to be hired on “Saturday Night Live” when it aired in 1975.

Following her life from birth to death, director Lisa D’Apolito lets Radner’s old journal entries narrate the documentary. Uncovered home movies of Radner’s childhood in Detroit illustrate her selected, written memories that are read out loud. D’Apolito cleverly intercuts Radner’s childhood photos and videos with celebrity readings of Radner’s entries, celebrating and showcasing Radner’s impact on the show and on comedians today.

The selections of both the voiceover pieces and the home videos are well-construed — building a quick exposition was clearly the intention of the editor. What could have been overdone and made overwhelming was edited out, allowing the audience to take in only the necessary details of Radner’s upbringing.

However, the film isn’t all laughs. The audience gets to explore Radner’s mental illnesses, including depression and eating disorders, and how she grappled with satisfying an intrinsic human desire: to be wanted.

Arguably, Radner’s own view of herself is somewhat contrary to how the public loves to portray her. Her journals recount her recurring and desperate need of love, affection and approval in everything she strove for. Time devoted to Radner’s one-woman show on Broadway focus more on how lonely it made her feel. Clips from a live-taped version of her show are mostly of Radner by herself backstage or in her dressing room, which creates a sense of loneliness when she is seen on stage. The director cleverly highlights the tension between Radner’s self–esteem and the audience’s praise for her. Her need for affection often overshadowed her creativity. Radner concluded that although she loved being a woman, she understood her gender came with limitations, especially within the culture of comedy. The film points out that Radner’s feminist status developed more from circumstance than out of personal agenda or passion.

But the politics of performing was never something she signed onto — Radner shined the most when she was onstage. Radner’s iconic “Weekend Update” characters, from the stark and raunchy Roseanne Roseannadanna to the sweet and elderly Emily Litella, struck a chord with audiences tuning in live all over the nation. This was a rarity in network television — most shows wouldn’t dare have female characters who exhibit any amount of personality. Radner opens up, further, in her entries, exposing that she often used her own experiences to cultivate this band of characters and often used them to propel herself through difficult times. The film makes a beautiful point in noting that Radner’s humor helped her as much as it helped those who loved her.

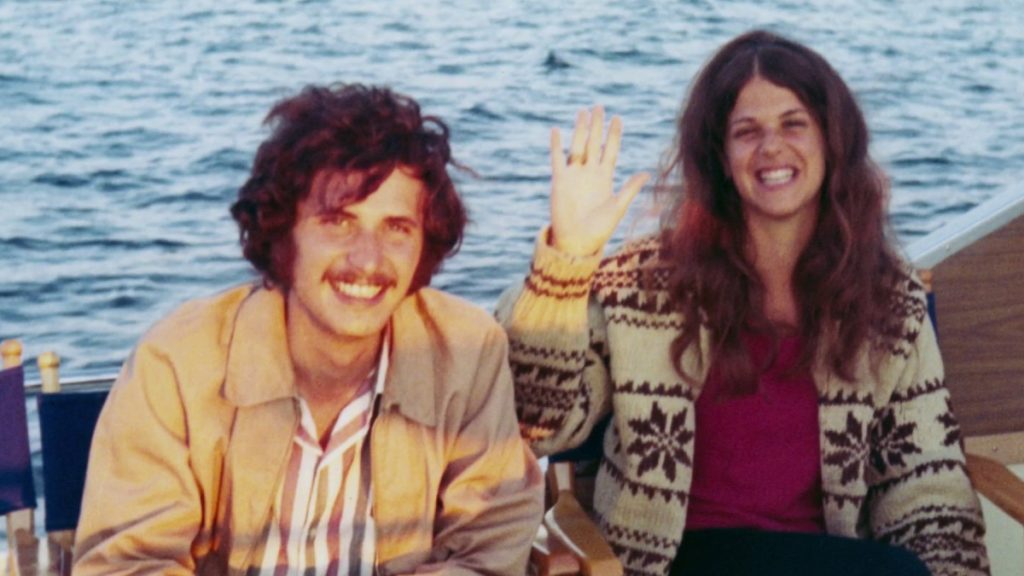

Disappointedly, the star-studded appeal of the documentary may have overshadowed the quieter, more intimate voices in Radner’s life. Although much of the story delves into her personal life, the film consults very few people outside her professional circle. The few close friends and family members interviewed are incorporated sparsely. Sentiments from her nephew and childhood best friend are as close as this documentary reaches into Radner’s personal life. Most recounts of her relationship with her second husband, Gene Wilder, come from celebrity ex-boyfriends and television producers.

Unfortunately, the excitement of her journey, at times, feels cumbersome and, in turn, the story flops in the peak of the second half. Because real life does not often mimic a typical Hollywood storytelling structure, it may have been more compelling to mix up the timeline of Radner’s life events in order of theme, not time. However, D’Apolito makes it clear to the viewer just how important the time period was to Radner’s ultimate success.

The film’s theme is bittersweet: Radner, herself, expressed that, everything she did, she did in pursuit of love. Through sudden fame, a failed marriage, a successful marriage and two bouts with ovarian cancer in the 1980s, Radner proved to herself and others that comedy was her most effective medicine. Her legacy, her insecurities and her queries, to her, are all irrelevant: In the end, Gilda Radner got the last laugh.