Ithaca College resident assistants and other students are now being trained to administer Narcan — a drug that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose — in a pre-emptive effort to combat drug abuse at the college.

Illegal opiate use at the college rose 2.8 percent to 3 percent from 2015 to 2017, according to the National College Health Assessment. While this is a small increase, the national average for opioid use is also rising slowly, from 4.5 percent to 5 percent between 2015 and 2017. Because of this, the college has started training all students interested, including resident assistants, to use Narcan — the brand name drug that delivers naloxone — as a preventative measure against opioid drug abuse or overdoses.

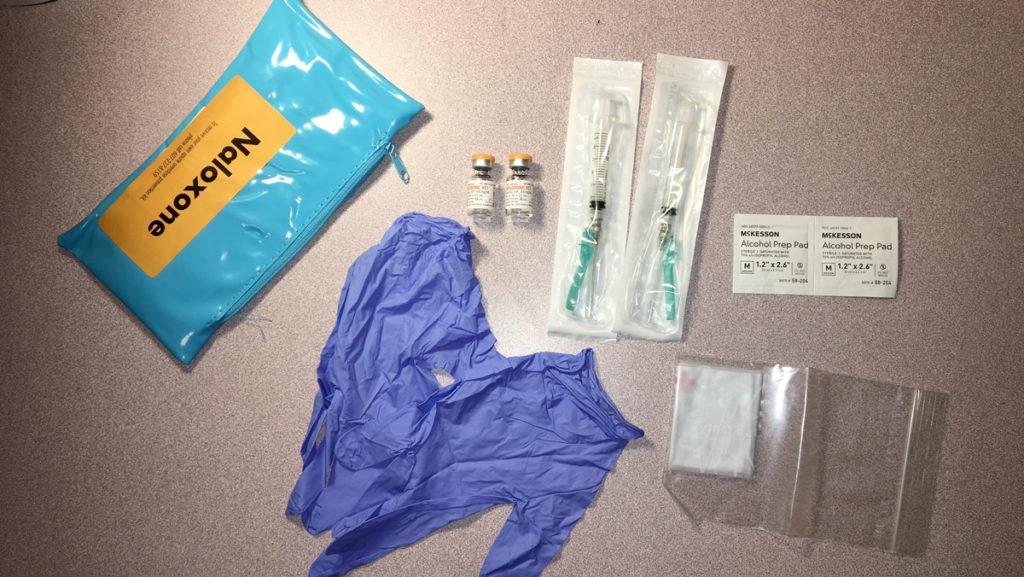

Naloxone is a medication that binds itself to opioid receptors to reverse the depression of the central nervous system and respiratory system, caused by opioids, allowing the person overdosing to be able to breathe properly. The drug comes in the form of a nasal spray and an injection.

In 2017, the Center for Health Promotion at the college participated in the biyearly National College Health Assessment. Opiate use, in this study, refers to the illegal use or misuse of opioids — like heroin, synthetic opioids and prescription pain relievers — rather than legally prescribed medications. Narcan, or naloxone, is a medication designed to rapidly reverse opioid overdoses. Nancy Reynolds, program director of the Center for Health Promotion, said the naloxone training is how the college is proactively attempting to prevent overdoses from occuring on campus. In 2015, the survey found that 0.2 percent of students at the college have used opiates not prescribed to them in the past month, compared to the national level of 0.5 percent. Only 718 out of 3,062 students responded to the NCHA survey.

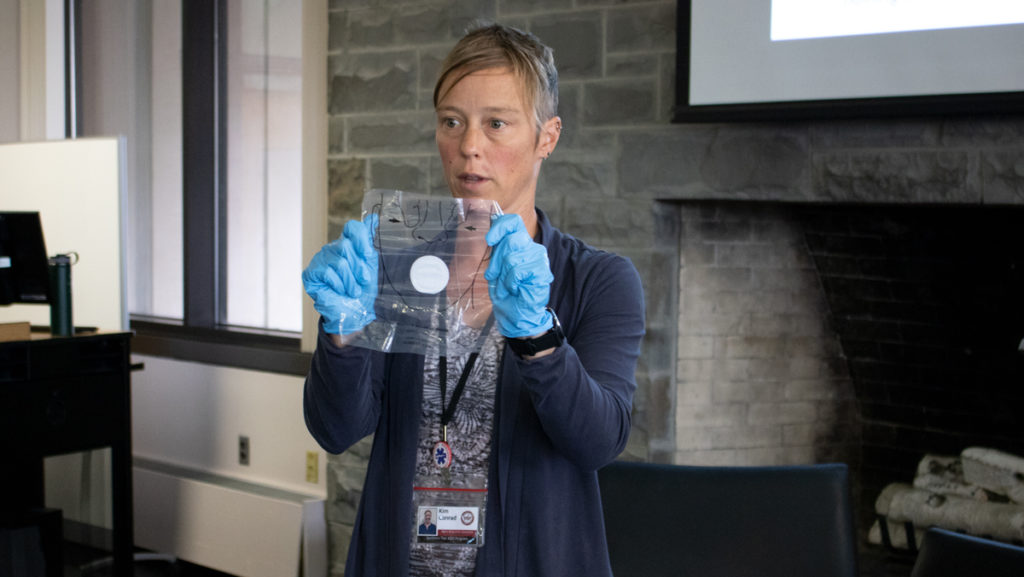

Although there have been no student, faculty or staff overdoses in the college’s history, Reynolds said, the college wanted to offer Narcan training to raise awareness about increased drug use and prevent any deaths due to overdoses on campus. The first training session of the semester, held Sept. 11, was led by Kim Conrad, harm reduction specialist at the Southern Tier AIDS Program, who taught how to administer naloxone and what the warning signs are when someone may have overdosed. The college will be having more workshops that will be open to all students Oct. 4, April 18 and April 25.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were over 63,000 fatal drug overdoses nationally in 2016, which is a 20 percent increase from 2015. College students make up one of the largest groups of drug abusers nationwide. The center found that college students turn to drugs to cope with high levels of stress, to stay awake later to complete their heavy course loads and to experiment, often as a result of peer pressure. While people from ages 18 to 24 are already at a heightened risk of addiction, the center found those who are enrolled in a full-time college program are twice as likely to abuse drugs and alcohol than those who do not attend college.

Opioid use at the college

Reynolds said the college is unable to keep a comprehensive list of all instances of drug use on campus because of the various options available to report it. For example, some students may go to the Office of Public Safety and Emergency Management when reporting drug use, while others may go to the Hammond Health Center. Tom Dunn, Public Safety administrative lieutenant, said Public Safety has the same issue keeping records because Public Safety officers can only report drug use when they find drugs on a scene.

Dunn said all Public Safety officials are required to have training on how to use naloxone in order to assist people in an overdose scenario.

Reynolds said the college records the number of times Public Safety, paired with medical assistance, is dispatched for all instances of drugs use including alcohol, benzos and opiates. In the 2016–17 academic year, Public Safety assisted 47 students for drug use, while in the 2017–18 academic year, Public Safety assisted 35 students, Reynolds said. During the 2018–19 academic year, as of Sept. 25, Public Safety has assisted 12 students, she said. Reynolds said these numbers do not include those who are transported to the hospital or caught using drugs off campus.

Dunn said Public Safety focuses more on students who are caught selling or owning illegal drugs because officers need evidence to report instances of drug use. Dunn said that, in 2018, there have not yet been any cases in which opiate use has been reported to Public Safety. In 2017, he said, there was one case of illegal oxycodone use, which was an opioid-based prescription. In 2016, he said, there were no cases. In 2015, he said, there were two cases of heroin possession.

Mixed reactions for training to reverse drug overdoses

Many students — ranging from RAs to Student Auxiliary Safety Patrol members — had mixed reactions to the Narcan training, which was optional for them to complete. While some were open to having the opportunity, others were apprehensive about having additional responsibility that requires extensive training — RAs who attempt to reverse overdoses with Narcan could be faced with a

life-or-death scenario.

Senior RA Taryn Falkenstein said she came to the training session because she interned at an organization that raised awareness about drug addiction, particularly opioid addiction, which is something she is passionate about advocating for.

“I will definitely get the kit after this presentation and would feel comfortable administering,” Falkenstein said.

Sophomore Chris Griswold said he thought this training would be helpful for his position with the Student Auxiliary Safety Patrol. He said his job entails walking the campus day and night to ensure student safety but said he would not have been comfortable treating an overdose scenario before the training. Although, Griswold said, it is important that students have a choice whether or not to complete this training because it is stressful.

“I feel like it is something that they should get to choose,” Griswold said. “If someone is up for it and ready to take that kind of responsibility, they should do it, but it’s definitely an added stress.”

Sophomore Hope Porrazzo, an RA in Landon Hall, said she did not attend training because she was unaware it was happening, but she said she would not have taken it even if she had known. She thinks that RAs should not be responsible for treating drug overdoses and that they should be handled by Public Safety officers.

“I feel like it could potentially add on stress to an RA’s job,” Porrazzo said. “We are taught to be the resource for the residents. … It is not our duty to take on the role of something bigger than an RA.”

Tony George, chief of the Addictions Division at Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute, said the college’s new program is advanced compared to programs he has seen at other colleges.

“It sounds like Ithaca College is on the cutting edge here,” George said.

George said, besides treating overdoses, another big factor in combating the opioid epidemic is education through programs like the Narcan training.

He said it would be beneficial for the college to pair the Narcan training with educational awareness programs about mental health to create an overall healthier college culture. College students are especially vulnerable to opioid addiction because of the added stress of college, George said. Additionally, he said an abuser’s unstable environment and a genetic history of addiction are also leading factors of opioid abuse.

“We always like to say genetics loads the gun and environment pulls the trigger,” he said.

Conrad said her office has found that many drug overdoses that were treated with naloxone in the Tompkins County area were conducted by nonmedical professionals.

“In 2017, we reversed almost 500 overdoses, and that wasn’t just us,” Conrad said. “It was people in the community. We ask people to come back and report that they used it and to report how to went — both to get a new kit and also so we can track how effective what we’re doing is”

When someone is unconscious or showing signs that they have been affected by drugs, Dunn said the first thing they should do is call Public Safety.

“Everyone is encouraged to call,” Dunn said. “If you see someone in distress, call. That’s always the golden rule.”

For students who are trained to use naloxone, Dunn said the office would want them to use their training if it is safe for them to do so. Training should discuss and educate attendees on whether a situation is safe or not safe to help revive a student, Dunn said. If the student suffering from an overdose or drug abuse is in a dangerous location or if reviving the student would put someone in danger, then the revival should be left to Public Safety. It is typical for people who have been revived from an overdose to wake up irritated and lash out by hitting the person who revived them, Dunn said.

“We would want the person to do what they could to make sure the person is breathing,” Dunn said. “If you don’t have any medical training, we want you to stay on the phone and keep us updated with what is the condition of the person.”

Sean McCabe, research professor in the Department of Women and Gender Studies at the University of Michigan, studies the forms of opioid use and misuse. McCabe said he is skeptical that the Narcan training will be beneficial in the long term because the drug itself is fairly new and has not been tested extensively. He said any program like the one at the college should also provide substance abuse assessments, substance use treatment and university lifestyle supports such as substance–free housing and 12-step programs provided on campus.

There is a substance free community for freshmen on the ground floor of Rowland Hall in the Quads and for upperclassmen on the first floor of Terrace 3.

“Narcan will never reverse opioid misuse,” McCabe said. “It only treats overdose.”

Contributing Writer Sara Oliver contributed reporting to this article.