On March 23, the Cornell University Student Assembly passed a resolution that strongly urged administration to require faculty to provide students a warning for content that could potentially be triggering, which reignited a debate about the use of trigger warnings in higher education.

A trigger warning should be used when presenting content that might provoke post-traumatic stress disorder and its related symptoms among students, according to the resolution. They are usually employed to give students the option to temporarily excuse themselves while discussing sensitive topics in a specific context and situation that makes them uncomfortable.

Cornell sophomore Claire Ting co-sponsored the resolution, along with sophomore Shelby Williams. Ting said that once the Cornell Student Assembly votes on a resolution, it is sent to Cornell President Martha Pollack, who can then choose to either acknowledge, accept or reject the resolution. On April 3, Pollack rejected the resolution.

The rejection attracted national attention from publications like the New York Times and Forbes to the use of trigger warnings in higher education and the compromise of free speech.

On March 29 the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression published an article, which explained that Cornell must not accept the student assembly’s resolution because it could potentially compromise free speech and go against Cornell’s academic policies. In their statement, Cornell Provost Michael Kotlikoff and Pollack said they rejected the resolution because it compromises academic freedom and freedom of inquiry.

“Requiring that faculty anticipate and warn about all such situations … would unacceptably restrict the academic freedom of our community, interfering in significant ways with Cornell’s mission and its core value of Free and Purposeful Inquiry and Expression,” Pollack and Kotlikoff wrote. “Such a policy would violate our faculty’s fundamental right to determine what and how to teach … it would unacceptably limit our students’ ability to speak, question, and explore, lest a classroom conversation veer into an area determined ‘off-limits’ unless warned against weeks or months earlier.”

Ting said she decided to propose the resolution after she observed that one of her close friends was visibly distressed while reading a graphic rape scene in class. Ting said her friend had been a victim of sexual assault and had recently taken official action against her assailant.

“What personally was a little bit egregious to me was that her professor knew that she was a victim of sexual assault,” Ting said. “And this was not anything particularly new because she had already been in contact with this professor regarding the Title IX process. So to me, this stood out as a lack of compassion. To give advance notice and context to the content of class material might [have been] more sensitive.”

Ting said she wishes that professors would use trigger warnings because it is essential for students to academically succeed while studying emotionally difficult content comfortably.

“A lot of the headlines online have really mischaracterized this resolution and even [painted] Cornell as a university of triggered snowflakes and children [of a] liberal agenda [that] has gone too far,” Ting said. “[Williams and I have] both been exposed to graphic and disturbing material, and we completely agree [that] interacting with this difficult material is essential for learning and for growth. The most important part though is just meeting that content with compassion.”

Fewer than eight of over 800 respondents to a survey conducted by the National Coalition Against Censorship reported that their institution had a policy regarding trigger warnings in place. Ithaca College does not have an academic policy about trigger warnings.

In 2016, the college’s faculty engaged in discussions about policies regarding trigger warnings and it was ultimately decided that professors should not be required to give content warnings in class, according to previous reporting by The Ithacan.

First-year student Shai Altheim said that as a cinema and photography major, they had to watch many films for their Introduction to Film Aesthetics and Analysis class that should have had trigger warnings. Altheim said they noticed that many scenes depicted visuals of sexual assault and some were inappropriate for photo-sensitive individuals who could suffer from seizures.

“A lot of me and my classmates were concerned about that,” Altheim said. “These are older films, and they’re all on Kaltura Media Gallery, so they don’t have trigger warnings in them and you can’t just search up and see if it has trigger warnings on it, because they’re so obscure. So the only one who actually knows about these films is [the professor].”

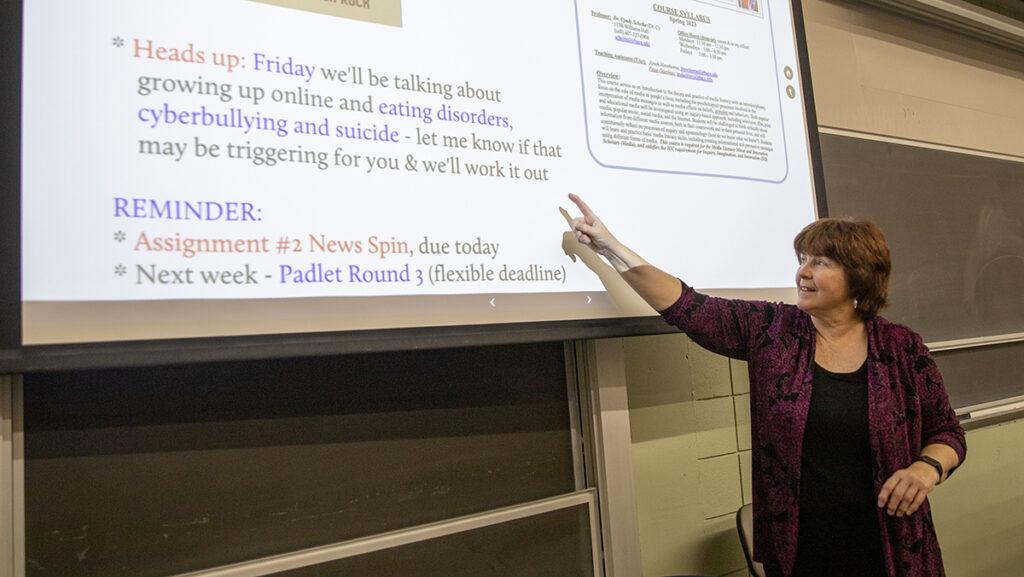

Cyndy Scheibe, Dana professor in the Department of Psychology and executive director and founder of Project Look Sharp, a nonprofit media literacy program based out of the college, said she gives trigger warnings a couple of days in advance of her classes and allows students to set up a private meeting with her to go over the topics.

“For me, it’s just giving people a heads up,” Scheibe said. “It doesn’t mean I’m not going to talk about it or show challenging stuff. … There are ways to make people feel safe, besides somehow protecting them from tough stuff.”

Scheibe said that while she is not in favor of course content being centrally mandated by administration, faculty should take the responsibility of presenting triggering content sensitively and responsibly.

“I also think, however, that it’s useful for a college or university or school district to have faculty consciousness raised about this,” Scheibe said. “Having that information out there, making that part of professional development stuff that we do, I think is useful because some people may not use trigger warnings because they just really don’t understand.”

Scheibe said that if a college-wide policy is put in place regarding trigger warnings, there would be gray areas about what counts as a trigger and what does not. Scheibe said the subjectivity of disturbing content will be difficult to navigate in policy making.

Ting said that having a campus-wide mandate would lead to logistical challenges, but that a common solution can be found.

“I think the middle ground would be establishing a standard for a sensitive approach to sensitive content,” Ting said. “If the nature of the certain material is inherently disturbing, then it shouldn’t be ridiculous to … respond to this disturbing content with a more nuanced and aware approach.”

Ting said she has had a positive experience working with Cornell leaders to find a solution that works well for students, administration and faculty involved.

“I’ve actually been met with a lot of fairness from the administration,” Ting said. “President Pollock and Vice President Lombardi came into last week’s student assembly meeting, where they explained — and we’re open to discussion [about it] — of striking a greater balance of free expression of compassion and meeting the needs of the student community.”

Sabrina Conza, program officer of Campus Rights Advocacy at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, wrote the article that outlined why Cornell University should reject the student assembly’s resolution about content warnings.

Conza said academic independence and freedom of faculty are compromised when a central, campus-wide policy is mandated.

“The faculty have the right to include trigger warnings, they have the right not to,” Conza said. “But when the administration gets involved in faculty’s teaching practices, that is when the professor’s academic freedom rights are violated.”

Conza said that studying all types of content in classes is essential for students to be better prepared for life after college.

“When someone tells you that this content is going to … hurt you, then that usually happens,” Conza said. “It’s like a self-fulfilling prophecy. … Even if students do find it difficult, it teaches them that they are able to confront difficult material in the classroom and also in the outside world, which they’re going to have to do without trigger warnings after they’re out of school.”

Trigger warnings are effective in preparing an individual to study or consume disturbing content and thus minimize the intensity of the effect the content might have on the individual, according to a study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan. However, trigger warnings minutely increase the anxiety of those dealing with tough or disturbing content, according to another study conducted by the National Library of Medicine.

In response to FIRE’s article, Ting said news and media companies use content warnings while playing graphic scenes on air.

“I’d say that much of what’s been going around in FIRE and conservative spaces regarding the resolution has effectively mischaracterized the content and the intention of the resolution,” Ting said. “First, I completely agree that professors should have free expression and academic freedom. I mean, I have the privilege to attend such a prestigious university. So of course there’s a trust from me … to my professor that whatever content I’m presented with — even if it is challenging or disturbing — that there’s some sort of academic value for me to derive from that. That can exist at the same time as compassion and courtesy for students.”

Scheibe said trigger warnings are not meant to protect students from tough content, but to help them learn that content with ease and at the pace they need to.

“I appreciate that part of it: We don’t want to just protect students so that they don’t experience anything difficult,” Scheibe said. “ I think the issue that comes up is not, ‘Are you dealing with challenging material?’ I think it is the surprise [of] not knowing that this is going to come up.”

Altheim said trigger warnings should not be a difficult accommodation for faculty to include in their course design.

“You’re in class, you think you’re safe, and then the professor shows this and you have a panic attack, what do you do?” Altheim said. “It shouldn’t be such a big deal for professors to do this. They could just … write it down. Like, it’s not that hard guys.”

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article said that a resolution passed by the Cornell University Student Assembly “strongly encouraged” faculty to use trigger warnings. This has been changed to accurately reflect that the resolution strongly urged administration to require faculty to use trigger warnings.