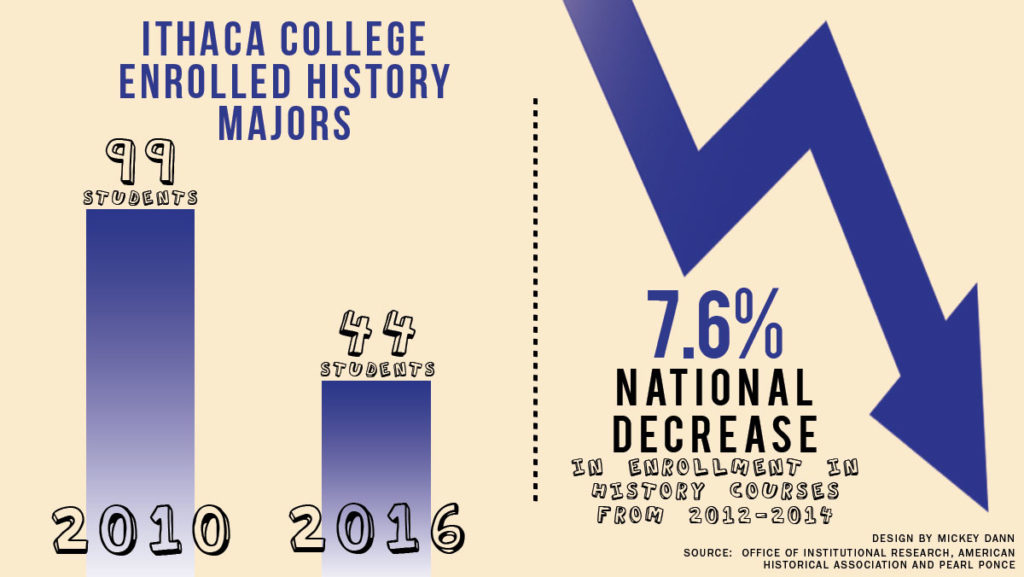

Student enrollment in the history major at Ithaca College has decreased by more than half in the last five years, following a national trend in the decrease of history majors nationwide.

A survey released by the American Historical Association this month found that there was a 7.6 percent decrease in undergraduate enrollment in all history courses from the 2012–13 academic year to the 2014–15 academic year. The college’s department currently has 44 undergraduate history majors for the Fall 2016 semester compared to the 99 undergraduate history majors who were enrolled in the Fall 2010 semester, said Pearl Ponce, associate professor in and chair of the Department of History.

Ponce attributed the decrease of interest in the history department to multiple factors, such as the increase in STEM courses, the 2008 recession that caused many students to lean toward supposedly job-secure preprofessional programs and the misconception that history majors do not get jobs.

“There is no question we’ve had a decline,” Ponce said. “But that’s not uncommon, and it’s certainly not particular to Ithaca College. Anytime we have a recession, we typically see a decline in all humanities majors.”

Data from the college’s Office of Institutional Research also show that other humanities majors at the college, such as English, art history, politics and writing, have also seen a steady decline in enrollment in the last five years. Majors under the STEM program, such as mathematics and computer science, have seen an increase in enrollment at the college, institutional data show. The number of enrolled computer science majors has doubled from 20 in Fall 2012 to 42 in Fall 2016; the mathematics major had 24 students in Fall 2012 and now has 34.

Ponce said another element that accounts for the decline in history majors at the college is the restructuring of the general education program. With the Integrative Core Curriculum, she said, course requirements no longer have “the historical or global overlay” that previously exposed students to the history department, unlike the previous general education program.

Ponce said the misconception about job certainty and what careers are available to a student who graduates with a history degree is also affecting this decline.

“Parents want their children to have a sense of certainty. And so, they favor their children to have majors where you can see a straight line from the major to a job,” Ponce said. “And I don’t think there is enough understanding because of course, one of the things a history major does, is it prepares you for any number of careers. And sometimes it’s hard to see that path.”

Julia Brookins, the special–projects coordinator for the American Historical Society, said the skills students acquire when they get a history degree, such as critical thinking and the ability to communicate clearly, are valuable in the workforce.

“When you talk to people about what they need for employees and innovation globally, a lot of the things that come up are things that you could learn if you have a broad-based education,” Brookins said.

Critical thinking was a skill highly rated by employers in a study from the Association of American Colleges and Universities in January 2015. Eighty percent of employers surveyed said they think the skill of applying liberal arts knowledge to a real-world settings is “very important,” according to the study.

Senior Evan Denning said he has not noticed the decline in the number of students in the history department. Denning said he thinks to draw in more history majors, the college needs to draw attention to, and contest, the stigma given to history majors: that the job market is not open for them. Denning said he also thinks other fields of study should be incorporated into the study of history.

“I’m a finance minor, and I find there is a lot of crossover between business, economics, finance and history,” he said. “I think if history can be taught in a way where it links other subjects, it would be advantageous to getting more students involved in history majors.”

Denning said he thinks history will always be relevant and does not think this trend exhibits the death of history.

“I think there will always be people just like me, who will always be interested in pursuing a history major,” he said.

The national focus on STEM programs, curriculums based on science, technology, engineering and math, at the high school and collegiate level, has also negatively affected the amount of focus on the importance of history, Brookins said.

Both the college and the American Historical Association are taking steps toward recruiting more students to major in history. The AHA has a national program called the Tuning Project which works with around 165 faculty members at almost 120 collegiate institutions. The goal of the project is to have individual history departments promote interest in history to students already enrolled in their colleges, said Brookins.

Ponce said the college does not have a formal plan to address the decline of history majors, but the department does outreach to exploratory students to expose them to the department, and there are also alumni speaker series to show what career paths are available post-graduation for history majors.

“I think we need to do a better job of articulating the very many paths you have,” Ponce said. “There are, in fact, many different ways to use your history degree, so a little more marketing many be in order,” she said.

This article has been updated to reflect the following correction: Pearl Ponce’s name was incorrectly spelled.