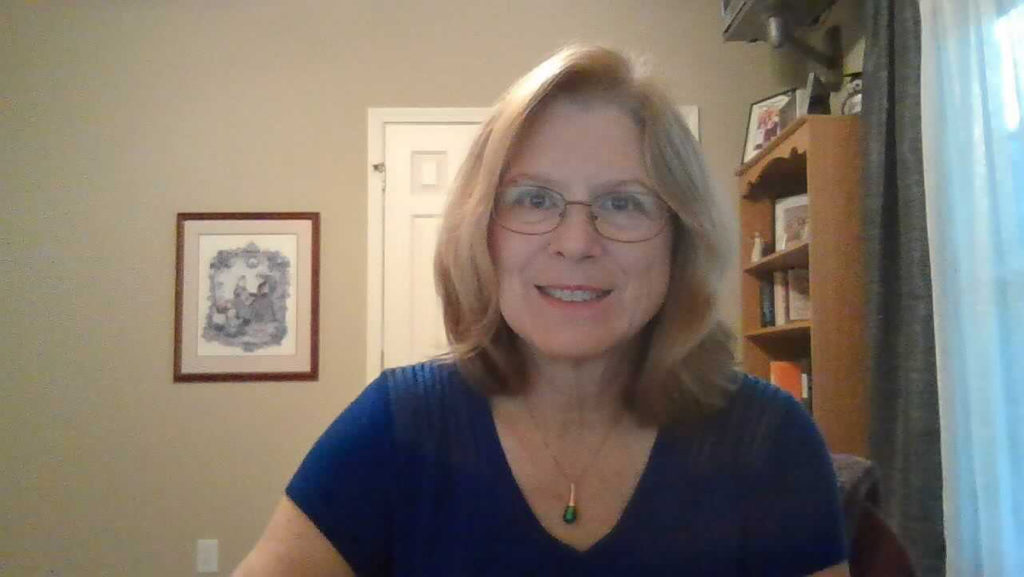

Joslyn Brenton, assistant professor in the Ithaca College Department of Sociology, recently published a book that she co-authored that looks at the relationship among childhood obesity, motherhood and social class.

The book, titled “Pressure Cooker: Why Home Cooking Won’t Solve Our Problems and What We Can Do About It” follows 12 mothers in their daily lives of motherhood, specifically looking at the way culture, socioeconomic class and food affect these mothers, their children and family dynamics as a whole.

Opinion editor Kate Sustick spoke with Brenton about her book, the research used in the book and the importance of sociology when analyzing health and food structures.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kate Sustick: What inspired you to go into this specific discipline within sociology?

Joslyn Brenton: I actually started out as an occupational therapy major. … My parents didn’t go to college. … My guidance counselor figured out that I would be good in a health field. … I picked occupational therapy. … Sociology was just a prerequisite. I didn’t even know what it was, and I remember it was an 8 a.m. class that I went to because I felt I had to. … I like to joke that [when I went to the class], the sky opened up and an angel sang and the light shone down on me. I couldn’t believe that people could do this for a living. I’d always been a studier or observer of human behavior, and I love human interaction. … My guidance counselor was right though. I do like the health and illness kind of research but as a sociologist. The health [aspect] does interest me still because there is so much inequality embedded within health processes. Health is a social process. We tend to think of it as a biological process, but it is an incredibly social process. I never lost that angle.

KS: Could you tell me about the book you recently published?

JB: The book starts in North Carolina, and that’s where we collected the data. At the time, I was a graduate student getting ready to start my dissertation work. … Two professors in my department had applied for a multimillion–dollar grant to study childhood obesity, and they got it, which sociologists do not often get such large grants. They needed research assistants … I became one of their lead graduate student researchers, and I had to figure out “What’s my big question here?” The study became about questioning this very idea of an obesity epidemic and questioning the stuff that has been written about it prior to our study. [What has already been written] is a lot of assumptions about mothers and the ways mothers are feeding their children and mothers’ inability to really understand whether their children are overweight or not. All of the research was pointing in a direction of blaming mothers, and, therefore, all of the interventions were being targeted at mothers. “Mothers need more cooking classes. Mothers need health education classes. If we can just make these women understand better ways to feed their children and to be able to correctly identify when their children are overweight, this is going to help us solve this problem.” As sociologists, we asked, “Is that true?” We started digging into the literature, and we found out nobody is asking mothers what they think. Nobody’s even talking to mothers. … Nobody is actually trying to get an understanding of how women experience this phenomenon of being expected and demanded to put a meal on the table. Nobody asked women, “What’s this like for you?” So that’s what we did. It was a five–year study. It started in 2012, and we followed 120 low–income mothers, white, black and Latina. … We picked an urban county, a suburban county and a rural county because the story of food is also a story of access. We started with interviewing them. Then we [realized] interviews aren’t enough. We need to actually be with them in their homes, follow them to the grocery stores, … so that’s what we did.

KS: Were there any requirements for involvement in the study?

JB: To get into the study, the mother had to have at least one child between the ages of two and eight because we knew we’d be following them for five years. That age range for children is the range when kids are adopting eating habits and range in which parents still have a large degree of control over what their children are eating. … We also picked this age range because it is the time in which mothers receive a lot of cultural and social pressure to feed their children in a very specific way and feed them the right kinds of food so they set them up for success in terms of eating. … As long as a mother had at least one child between the ages of two and eight, they could. And that they qualify income–wise because we’re really only following low–income mothers.

KS: It seems like extremely personal work. Were there ever moments in which it felt like too much?

JB: Every day. I was also pregnant at the time. I was pregnant with my [second child] as I was conducting these interviews. I am a mother too, and I am very visibly pregnant, … which helps and can backfire sometimes. We knew so many mothers who were just living in the direst of circumstances, people who had no cash income, were living in trailers with holes in the floors, people who didn’t have kitchen tables or chairs to sit at. … You leave these interviews and observations and feel all sorts of things. You feel sympathy. You feel a weird feeling of “Now I go home to my husband and my children who definitely have enough to eat.” … What does it mean for me to be a white researcher interviewing a poor mother of color? … Here’s a pregnant mother over here who’s unemployed and their only source of income is [Women, Infants and Children] food stamps, but then here’s this pregnant woman who is here to research [the other pregnant woman.] These are stark differences, and you have to think about “What does this mean for the data I’m collecting? What does this mean about the analysis I end up producing?” … In one of the chapters in the book, … I ride along with this mom and her mother, … and I’m in the backseat with the toddler [going] to the grocery store. It is a blazing hot day. [The mother] has no money, there’s a problem with her food stamps and her paychecks haven’t come in. We are [going back and forth] across town, and [we are all] dripping sweat. … We get home, and the mother and the grandmother are unloading the groceries, and then the husband starts berating the wife for getting the wrong flavor of Oodles of Noodles. … Every single situation just solidified this feeling of “I have to tell this story.” There is a huge story here to be told that nobody’s talking about when it comes to family life and feeding kids.