Every generation grows up labeled with a set of defining qualities, stereotypes and misperceptions, often brought about by either the conditions of the times or the opinions of its predecessors.

With the increased rate of change in technological and social advances impacting the experience of today’s college students, the debate over how to best work with and among them continues to evolve.

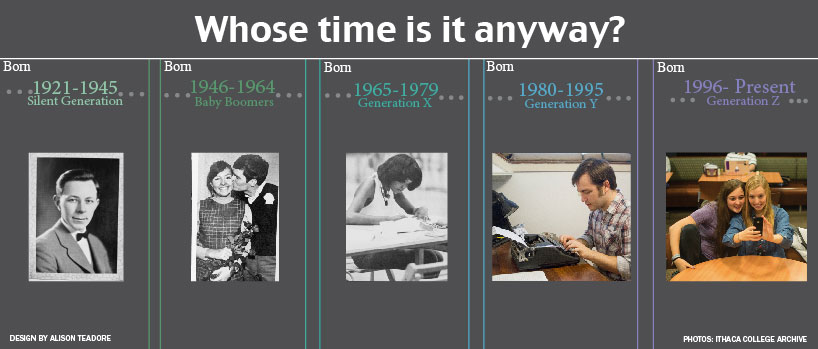

Though sources vary, most label the millennial generation as those who were born between about 1980 and the late 1990s, which includes the current cohort of college students. The Ithacan looks at millennials in terms of how they are perceived and how these perceptions play out in their academic, economic and social lives.

Part 1: Educators cater to different millennial learning habits

Part 2: Stereotypes convey sense of millennial entitlement

Part 3: Millennials facing greater competition in labor market

Educators cater to different millennial learning habits

by Kayla Dwyer, News Editor

Stephen Clancy, professor of art history at Ithaca College, displayed a list of terms and names for the upcoming test on the smartboard for his Episodes in Western Art class on Oct. 29.

Then came the barrage of students’ questions.

“What do we have to know about Pope Julius II?”

“What will we have to say about humanizing?”

“So we’re only doing one comparison on the test?”

With a calm demeanor, Clancy answered each student’s question directly and concisely, just as studies show is the preferred method of information transference among millennials.

The current college-student population sits at the tail end of the millennial generation, which has been held under scrutiny and observation for reasons both positive and negative, signifying a dismal or progressive future, depending on who is asked. While the popular outlook on millennials pegs them with an inability to think deeply and integratively — a practice supposedly lost with the immediacy of technology — data-driven evidence, or even many leaders in millennial research, hardly support it.

But studies do indicate a shift in the way these students — born between the 1980s and late 1990s — absorb and apply information, and how classrooms are evolving to cater to their needs and behaviors.

Now in his 27th year of teaching, Clancy said the key differences are evident in his teaching style: assigning shorter readings, organizing his lectures into an interesting, climactic progression and packaging ideas more overtly.

“I can simply look back to when I first started here … and I assigned longer readings, [and] I expected deeper engagement with the longer readings,” he said.

One popular explanation for this is the idea that millennials have physically different brains, wired differently as a result of growing up surrounded by technology. In response to this argument championed by Marc Prensky, author of the term “digital natives,” researchers from Partnership, the Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, could find virtually no evidence to support a physical change in the folds of the brain to explain any phenomenon in millennial intelligence.

Cynthia Williamson, collection and access services librarian at Mohawk College in Hamilton, Ontario, and co-author of the Partnership study “The Kids are Alright — or Are They?” said the brain certainly changes with learning, but not to the degree that millennials are fundamentally different simply because they are millennials.

“I’m a total proponent of neuroplasticity … but change is not because of your generation or when you were born or who you are, but because of the way you’ve been taught,” she said.

Leigh Ann Vaughn, associate professor of psychology at Ithaca College, said the schema development of students — the ways they learn to make connections — are influenced at a critically early age. In the case of millennials, she said the focus in secondary school on preparing for tests has had an influence on the way students know how to structure information themselves.

When it comes to learning and problem solving, sophomore Andrew Carr said he finds it frustrating when there is not one right answer.

“Even in critical thinking situations, it’s really frustrating when someone’s not there at the end to tell me, ‘Yeah, you critically thought correctly,’” he said. “We’ve been taught our whole lives that our intelligence is measured by whether we know information or not.”

Vaughn said despite students’ leaning toward flashcard learning, when given encouragement, students can easily pick up new methods of preparing for exams and writing pieces.

“Humans are remarkably adaptable,” she said. “You’re never done developing and growing at any point in your life — research is very clear on this.”

Freshman Hannah Cohensmith said at first, the transition from standardized-test preparation in high school to the lack thereof in college was difficult because she was very used to knowing more details of what to do, study or write in order to get certain grades.

“When I was writing my first essay for my seminar, I was going crazy … I know how to write, but we were taught to write to the AP [English] Language and [Composition] test,” she said. “I felt like it took me a lot longer because I never had such free reign over how to study.”

Clancy said today’s students tend to take in information in pieces and compartmentalize them, thinking of information as isolated pieces rather than connecting them.

“They grab little chunks of information, and keeping a sustained focus on one thing for a long period of time becomes more challenging,” he said.

While the current student cohort might have more difficulty dedicating more attention to deeper thinking, Leslie Lewis, dean of the School of Humanities and Sciences, said this is not so much a generational as a societal factor. Students now have to make a more conscious decision to find a quiet space without distractions, she said.

“If you don’t intentionally construct it, society will not give it to you,” she said.

Junior Jacob Ryan said he uses the Strict Workflow extension of Google Chrome to help him sustain focus for set blocks of time on one task. The user inputs distracting websites, the program blocks them for a predetermined amount of time, after which the user gets a short break determined by how many minutes he or she chooses to allot.

“Especially during midterms or finals, I constantly have that on just so that I make sure I’m getting work done in time,” he said.

Clancy said the attention spans of students today do not make them less smart. Rather, the expectations in the classroom have changed in regard to what and how much professors and students should do to contribute to their learning, which is a reflection of the learning shift.

“I can provide the kinds of things that I think are important, but I can do so in a format that they find engaging … It does require me to make more concessions,” he said. “Certainly when I was a student, the professors for the most part made no concessions.”

The concept of meeting halfway is how Ryan said he sees the ideal professor-student relationship.

“I guess it’s kind of a give and take,” he said. “It’s their responsibility to kind of adjust the course or try and throw in a little bit of creativity … to get the students engaged so they actually learn it rather than just throw a bunch of information at them, but at the same time, as a student, it is kind of up to me to make sure that if the professor is putting in the effort, I’m at least trying to engage with them.”

The Integrative Core Curriculum is a method through which Ithaca College attempts to remedy these changing expectations.

Lewis co-led the faculty taskforce to research integrative learning prior to the implementation of the ICC, which seeks to engage students in big-picture questions that, throughout their four years, they would seek to answer through several different methodologies.

“The research focuses on the way we understand that students often have a difficult time translating information from one context to another,” she said.

Carr said connecting his sight-singing exercises in class to his everyday life was a frustrating process, but one that resulted in a life-changing learning experience.

“Sometimes it’s hard to see those moments where your classes are all working together to form this single identity of who you are, but it’s really rewarding when that does happen,” he said.

Good or bad, conditional or biological, millennials are indeed different from previous generations at the same age, which is the core thesis of Richard Sweeney, university librarian at the New Jersey Institute of Technology.

The Chronicle of Higher Education has coined the term “Millennial Man” to describe Sweeney, who in 2005 came into the public eye with his research on millennial characteristics.

One of these key characteristics is the result of what he calls the “drinking from the fire hose” phenomenon.

“It’s coming at you too fast to be able to effectively swallow what’s coming in … you need to be able to have some time to process what you’ve learned,” Sweeney said. “The problem is when that next text comes in, it interrupts you in that moment.”

While perhaps not a physical rewiring, at least mentally, he said, millennial brains are geared toward expecting frequent interruptions even when they don’t occur, as a result of having those text and cellphone notifications that consistently interrupt trains of thought.

Cohensmith said she needs to keep her phone on silent while doing homework, but even then, she will check it frequently.

“Sometimes I’ll be like, ‘OK, once I finish this slide in a PowerPoint, I’ll check my phone,’ and I mean for that to be like a minute, and then I’m on it for 15–20 minutes watching videos,” she said.

Tom Pfaff, director of the Honors Program, said these are examples of the kind of outside factors and distractions that colleges and professors must compete against, which contributes to the perception that students are unable to sustain deep thinking.

Like Pfaff and Lewis, Alexander said millennials can absolutely apply themselves. It’s about the willingness to do it.

“It’s attitudinal — attitudes shaped by parents, shaped by teachers, shaped as you’ve gone through the pipeline,” he said. “You have the innate intelligence to do anything you want to do, if you want to do it.”

Clancy said the differences he notes in millennials in his classroom are indisputable, but to no credit or discredit to the generation itself.

“They’re neither good nor bad — they just are,” he said.

Design by Alison teadore

Stereotypes convey sense of millennial entitlement

by Kayla Dwyer, News Editor

With a lack of data supporting different brain structures or psychological attributes in millennials, experts find that generational stereotypes are rooted more in societal fads than scientific fact.

An AchieveGlobal study sheds light to stereotypes characterizing millennials as self-centered and self-serving. The study, “Age-Based Stereotypes: Silent Killer of Collaboration and Productivity,” states that these stereotypes are often the basis for tension among generations.

The most common of these: the millennial sense of entitlement.

Sophomore Andrew Carr said he thinks these viewpoints arise from discrepancies in how different generations perceive millennial behavior.

“We’re viewed as entitled because we go out and get what we want,” he said. “We’ve finally started empowering youth to be a part of society at a younger age, but then when we actually start to try to do that, it’s seen as this threat, and then to squash it, they tell us we’re entitled.”

Christopher Alexander, professor of business management at King’s College and co-author of “A Study of the Cognitive Determinants of Generation Y’s Entitlement Mentality,” said it is the culture of fast and instantaneous gratification — the immediacy of information through technology — that leads to the millennial sense of entitlement to quick information, instant results and rewards in the classroom.

“Without a doubt, millennials are very bright and much more technologically savvy than the previous generation, and I think it’s a gift, but a curse,” Alexander said. “You come to expect everything to be [quick], but it isn’t.”

He said this sense of entitlement his study observes has shown up rather vocally in his personal experience.

“Within the last 10 years, that attitude started creeping into the classroom — ‘You want me to do what?’ … One student had the audacity to say to me, ‘You know what, you can’t do this, I’m paying your salary,’” Alexander said.

But the reason millennials have these expectations and behaviors, he said, is because of external factors: societal rearing. He said parents and teachers, for example, expect millennials to process information faster and earlier than in previous generations.

“If people get frustrated by the behavior of millennials, all they have to do is look in the mirror,” he said. “I can’t find fault with anyone, it’s just society, that society is so fast now, that I think that has forced millennials to act the way they do. Unfortunately, the rest of the older world doesn’t see it that way.”

Without a sense of compromise — both society and millennials realizing the depth and shortfalls of their perceptions — tension among the generations will continue to persist because of the speed at which things are changing, he said.

Freshman Hannah Cohensmith said she felt this with her teachers and, at times, her parents.

“They get it wrong,” she said. “So many teachers in high school think our generation is lazy and doesn’t work hard like they did and has it easy with technology, when really, I think it’s the opposite. There have always been lazy kids, and I think other generations forget that.”

Junior Jacob Ryan said he believes millennials have been charged with fixing the mistakes of the past and adhering to prior generations’ expectations, and straying from these expectations is what creates tension and misunderstanding.

“I would much rather spend my time looking for ways to grow as a person, have enjoyable experiences, rather than just go into that office job … like a robot,” he said. “I feel like the expectation is put on us, and when we don’t meet that, that’s when they call us lazy or entitled. We don’t necessarily share the values they want us to.”

Millennials facing greater competition in labor market

by Jack Curran, Editor-in-Chief

As the end of 2014 approaches and members of a new generation prepare to begin their college careers, the millennial generation has nearly completed its emergence into the labor market. As the portion of the workforce that primarily entered the market during the 2008 recession, the skills, values and career ambitions of Generation Y, more commonly known as millennials, have been significantly shaped by the economic climate.

New research by the marketing firm DDB Worldwide suggests that millennials with full-time jobs have a stronger desire to get ahead than members of previous generations had in the early stages of their careers.

Denise Delahorne, senior vice president and group strategy director of DDB U.S., said it’s not surprising to see this desire because this generation has had more job instability since the 2008 recession than other generations.

“It’s very clear that millennials who have jobs are very eager to get ahead and are very conscious of doing well in those positions,” Delahorne said.

In 2009, the national unemployment rate reached 9.3 percent, the highest it had been since 1983, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Though the market is beginning to reach pre-recession levels with September’s unemployment rate being 5.7 percent — the lowest since 2008 — the unemployment rate for people aged 20–24 in September was 11.4 percent.

Despite this unemployment rate, the National Association of Colleges and Employers’ 2014 job outlook survey found that employers had planned to hire 7.4 percent more graduates than the previous year. NACE also reported a higher demand for millennials with degrees in business, engineering, communications, sciences and computer sciences.

With this high unemployment rate for young adults, some millennials are able to set themselves apart through small efforts. Rebecca Kabel ’14 was offered her position at Integration Point, a global trade compliance software company, more than two months before graduation. Kabel said getting a job was easy for her because she started her search early.

“I started sending out resumes around the end of September [2013],” Kabel said. “That’s why I had a job before I graduated. It wasn’t anything special.”

Design by Alison Teadore

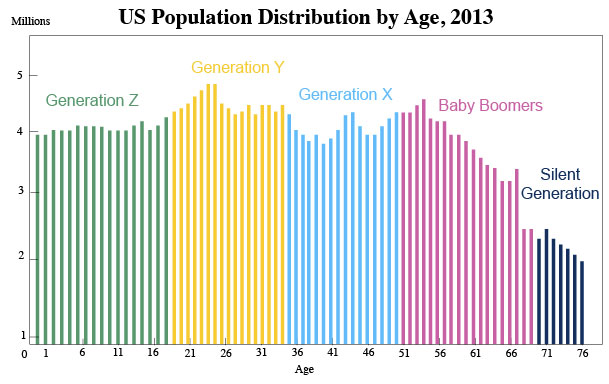

Though the recession impacted a large portion of the economy, it has not been the only factor that has influenced the success of Generation Y. Stacey Randall, founder and chief consultant of Randall Research, conducted research on how the recession impacted the millennial generation in 2011. Randall said not only has this generation entered the job market during the recession, it has had to deal with being bigger than the previous generation.

“When you think about a baby boomer who comes out of college, there are more of them than when their fathers and mothers went to find jobs, so they got really competitive,” Randall said. “It’s the same thing with the millennials now. They’re coming out a large generation, so they have to be competitive because there are more people to compete with, and we’re in an economic slowdown.”

Whether millennials are more eager to succeed or not, some studies have suggested that employers are not always impressed by this generation. A survey put out by Millennial Branding and Beyond.com asked employers from across the country about their impressions of millennials. Of the 2,978 respondents, 73 percent said they felt college only somewhat prepared students for the workplace.

John Bradac, director of the Office of Career Services at Ithaca College, said he has seen a recent trend of employers looking for technical skills from students. Bradac said he thinks this pattern has come from a decrease in employee training.

“I’ve seen a downturn in the amount of training and development of employees, so I hear a pretty large outcry from employers who are saying ‘You’re not giving me what I want,’” he said. “In other words, ‘I want the following technical skills, and you’re not training students in that area.’ I’m not sure that it’s the college’s job as a whole to prepare you for xyz software because that’s what company abc uses.”

Despite the demand for technical skills, the Millennial Branding and Beyond.com survey suggested that the traits employers desire most are a good attitude, communication skills and the ability to work in a team. In meeting with job recruiters, Bradac said he agrees that these are the most important qualities for job seekers to have.

On top of the preparation millennials receive from their colleges, many employers also expect potential employees to have internship experience. According to NACE’s internship and co-op survey, 96.9 percent of employers planned to hire interns in 2014. NACE also reported that since the 1980s, the percentage of college graduates with at least one internship has increased from less than 10 to more than 80 percent.

Delahorne said this increased emphasis on pre-employment experience is one of the biggest differences between the job market for college graduates now and in the past.

“I don’t remember the term ‘internship’ referring to anything other than a medical internship for the boomer generation, but it’s really become a way of life for the new generation in terms of gaining employment experience,” Delahorne said.

Though many students choose to take internships as their first jobs, Bradac said he recommends students avoid taking internships after graduation.

“I encourage people to not think about going into an internship after graduation,” Bradac said. “I encourage them to look for a professional position, and only after they’ve exhausted those opportunities to look at internships as a way to connect as well.”

As millennials continue to work through the job market, Delahorne said she thinks most millennials with jobs simply want to prove themselves because they appreciate their employment status.

“Given the economic times and the challenges that many people have had in terms of finding a job, I think that those who have jobs are very cognizant of the gift they have in that employment.”

Stephanie Lemmons ’14 began working for Heart for Africa, a nonprofit in Atlanta, in August after spending the summer applying to jobs. Lemmons said she got her position as trip coordinator and administrative manager through connections with a former employer. She said she appreciates her job and wouldn’t want to start another job search in the near future.

“It’s a battle of a process I don’t wish to have happen any time soon,” Lemmons said. “You get to a point where you’re like ‘OK, I’d really like to have a job now.’”