April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month, but women take measures to protect themselves from acts of aggression every day of the year.

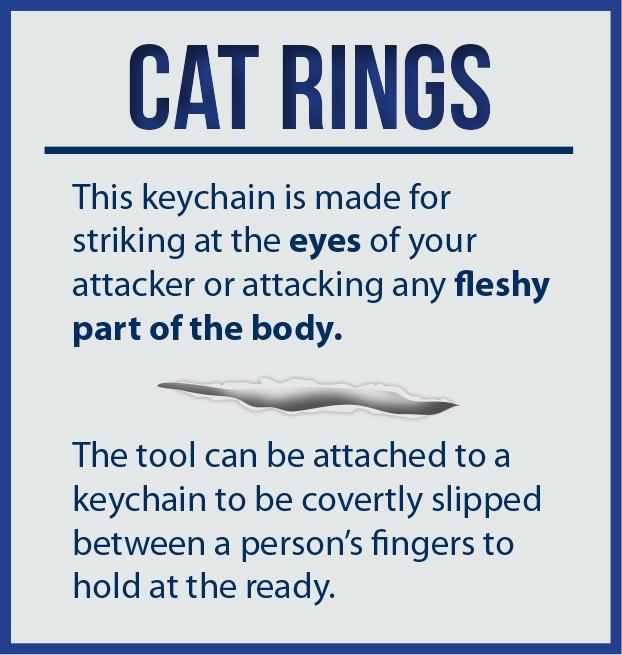

Many women at the college said they regularly carry self-defense tools like pepper spray, dog and bear spray, Mace and pocket knives to provide an extra sense of security when they go on runs, walk around at night or visit unfamiliar places alone. Women also reported taking self-defense classes to prepare themselves to act effectively in threatening situations without relying on these tools.

Sophomore Bridget Pamboris always carries dog spray with her and sometimes a pocket knife. Pamboris lives near New York City and said she has experienced close encounters there.

“This past spring break with my friend, we were walking back from a bar in the Lower East Side, and this guy was just following us,” Pamboris said. “He was coming within a couple blocks of our apartment, so I just took out my spray and told him to back off.”

She said Ithaca is pretty safe compared to the city, but she still doesn’t take chances.

“If I’m coming home late from a radio shift or one of my friend’s Circles coming back down to Gardens, I’ll just have it in my hand or my pocket ready to go, just in case,” Pamboris said.

Senior Samantha Guter said she always carries a knife with her.

“I just make sure that if something were to happen, that I would be fine to handle that situation,” Guter said.

Sophomore Melanie Kossuth also said she always carries Mace with her — and occasionally knives — if she goes on trail runs alone.

“I haven’t had to actually use them yet,” Kossuth said. “But I have been followed and verbally accosted before, and I’ve just tried to remove myself from the situation because sometimes saying no isn’t enough.”

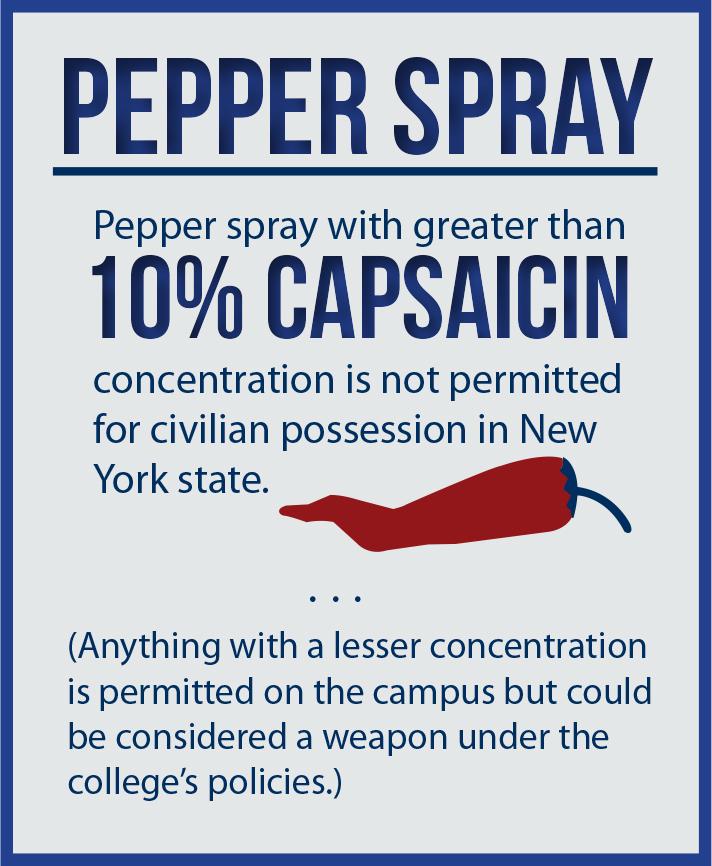

New York state has strict laws regarding the use of pepper spray, and the college complies with those regulations, said Andrew Kosinuk, crime prevention liaison for the Office of Public Safety and Emergency Management.

Other northeastern states like Connecticut, Maine and Vermont have no restrictions on pepper spray. A product with a greater than 10 percent concentration of capsaicin — the active agent in pepper spray — is not permitted for civilian possession in New York state or on the college’s campus. Anything with a lesser concentration, like dog or bear sprays, is permitted on campus but could be considered a weapon under the college’s policies, as with a pocket knife or other self-defense tools.

While self-defense strategies may vary, there is a general consensus among women on the necessity of taking measures to prevent victimization — especially in college.

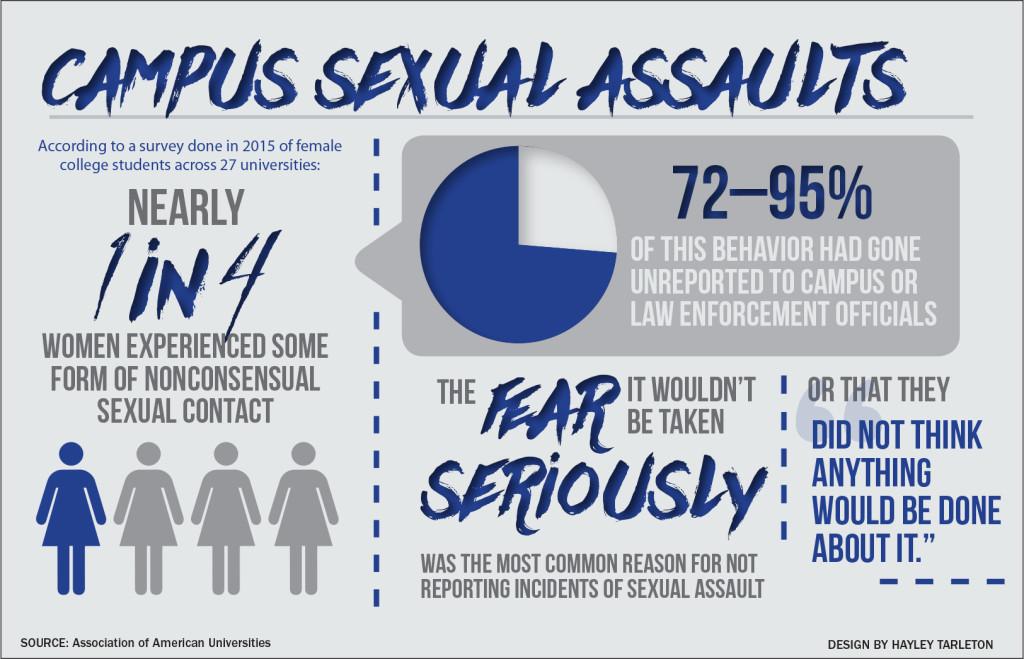

The Association of American Universities conducted a survey in 2015 that found among female college students across 27 universities, nearly one in four had experienced some form of nonconsensual sexual contact. The survey also found the overall rate of reporting this behavior to campus or law enforcement officials was as low as 5 percent in some cases, and never more than 28 percent.

Pamboris said women have to prepare themselves for situations in a college environment that can turn familiar faces into possible threats.

“Even if you trust somebody, you don’t know how they are when they’re intoxicated,” Pamboris said. “The group-guy mentality is just insane at colleges. A guy may not be like that, but in a group, he may act differently.”

Kosinuk said that while carrying a self-defense tool can provide peace of mind, they come with the serious risk that it could be used against you.

“That’s an advantage of physical self-defense that we talk about in self-defense classes, and another reason why we don’t necessarily encourage students to carry such tools,” Kosinuk said. “If they are disarmed of that tool, it could actually end up being used to harm them further rather than protect them.”

Each semester, the college offers a self-defense class titled Personal Defense that lasts about seven weeks. It is pass–fail and worth half of an academic credit. The instructor, Gail Lajoie, said the course aims to equip students with psychological and verbal skills that can help de-escalate conflict, physical techniques to escape violent situations and a belief that they are worth defending.

It is 7:58 a.m. on a Tuesday morning in the Hill Center. Students file into a large room covered with wrestling mats. They take their shoes off, put their bags to the side and sit in a circle. Lajoie walks in and joins the circle. Of the eight students, seven are women. The first 15 minutes of the class are spent talking about how to decide when to intervene in a hostile situation, anticipating the moment when words could turn to violence. Lajoie then tells the students to stand up and partner up. She asks, “What is the difference between yelling and screaming?” Students offer answers, and collectively, the class decides that yelling is directed whereas screaming is helpless.

As the students practice physical strategies of self–defense — how to properly fall, how to keep distance between themselves and the attacker — Lajoie repeats the same phrase: “Keep talking!” Your physical defense is just as important as your verbal defense. Talking attracts attention, Lajoie said, but more importantly, “If you’re talking, you’re breathing.”

Jarrett Arthur, women’s self–defense expert, trainer and the founder of Mothers Against Malicious Acts, a self–defense training system designed specifically for women and children, said the importance of self-defense training reaches beyond physical protection, as seen reflected in the college’s class as well.

Arthur said the fear of being in a situation where they have to defend themselves is universal for women, and it creates an emotional void that transcends into several aspects of their lives.

“I think that underlying fear and all of those unanswered questions leave a little hole in a woman’s life, and it affects all different areas of our lives from our romantic relationships to our professional and academic careers,” Arthur said. “That fear indicates a sense of powerlessness.”

In her 12 years of experience in self-defense training, Arthur said, she has noticed within herself and her clients a newfound sense of confidence that comes with learning how to defend oneself.

“On the surface, self-defense for safety is important,” Arthur said. “But beneath all of that is a much greater sense of personal power, self-advocacy and self-esteem.”

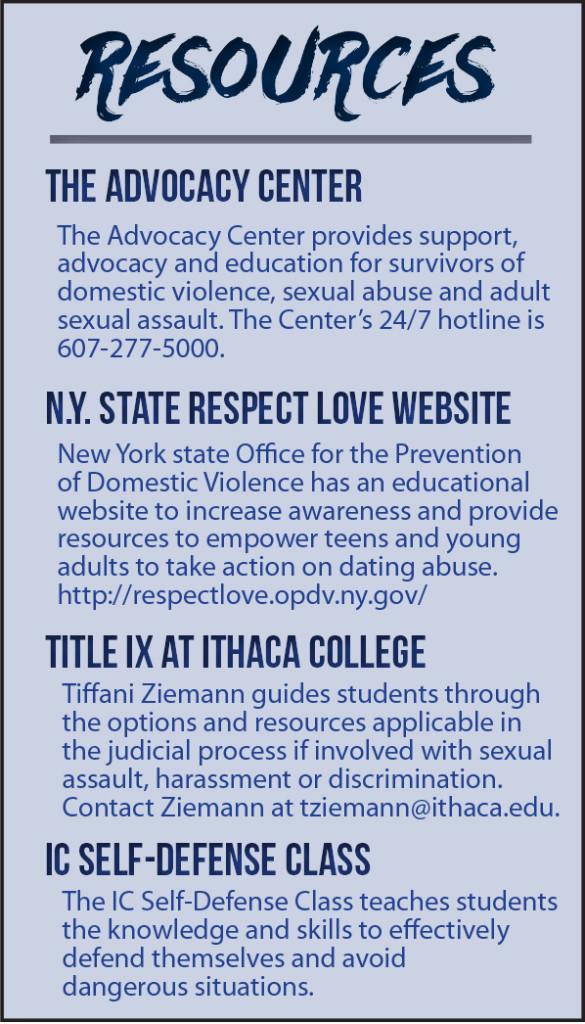

Tiffani Ziemann, Title IX coordinator, said while self-defense classes are a great tool to make people feel more confident, self-defense is a skill set that they should not have to learn in the first place.

Ziemann works with students on campus who are involved with sexual assault, sexual harassment or discrimination based on gender or sexual identity to find resources in the judicial process. She said the way society frames conversations about self-defense is problematic because it places too large of an emphasis on the responsibility of women to defend themselves from potential threats when there should be much more focus on eliminating the actual threatening behavior.

Ziemann said this idea does not just apply to women, but also to any minority community.

“If you identify as LGBT, or nonwhite on a predominately white campus, I think that the messaging is always about how to protect yourself from other people, versus other people should just not be doing things that make you feel unsafe,” Ziemann said.

Out of the eight students in this block’s personal defense class, seven said the college should do more to educate the campus community on sexual assault prevention. Ziemann said she hopes to see this happen.

“There are a lot of opportunities to teach the campus in general about culture and how we interact,” Ziemann said. “If we can take more steps to at least make it optional and available, people who really want and need it are going to find it and take advantage of it.”

Guter said the college should do more to advertise the self-defense resources offered on campus, especially to incoming freshmen.

Kosinuk said it is important to initiate these conversations immediately when students get to campus, if not before. While the college gives every incoming student an introduction to the Sexual Harassment and Assault Response and Education program during summer orientation, Kosinuk said, the program does not reach its maximum potential because it, like most others, focuses largely on after-the-fact response rather than prevention.

He said more can be done on this campus and nationally to prevent assaults from taking place.

“Talking about how we can experience broad-scale culture changes that forestall these issues instead of one at a time trying to put out the fire of individual incidents — that is where things need to be better,” Kosinuk said.

Guter said to start changing the conversation around women and self–defense, we have to start small. She said self–defense classes don’t need to stop but that they need to be more targeted toward everyone, not just women.

“Having those conversations with kids about consent and respect for others starting at a very young age is a good basis,” Guter said. “We need to be realistic about the fact that there are some things in our society that we perpetuate through media, conversations, stereotypes we uphold because we have inherent biases.”