The 2016 election of Donald Trump was surprising to a majority of the nation, since many news outlet polls predicted a Hillary Clinton win. But now the nation is looking to Trump to steer the republic — and he has made the direction he has chosen for higher education clearer since the election.

Trump recently appointed Betsy DeVos, billionaire and former chair of Michigan’s Republican Party, as secretary of education. DeVos is a proponent of privatized education, which has some pegging the decision as a defining embodiment of the Trump administration’s attitude toward future education policies.

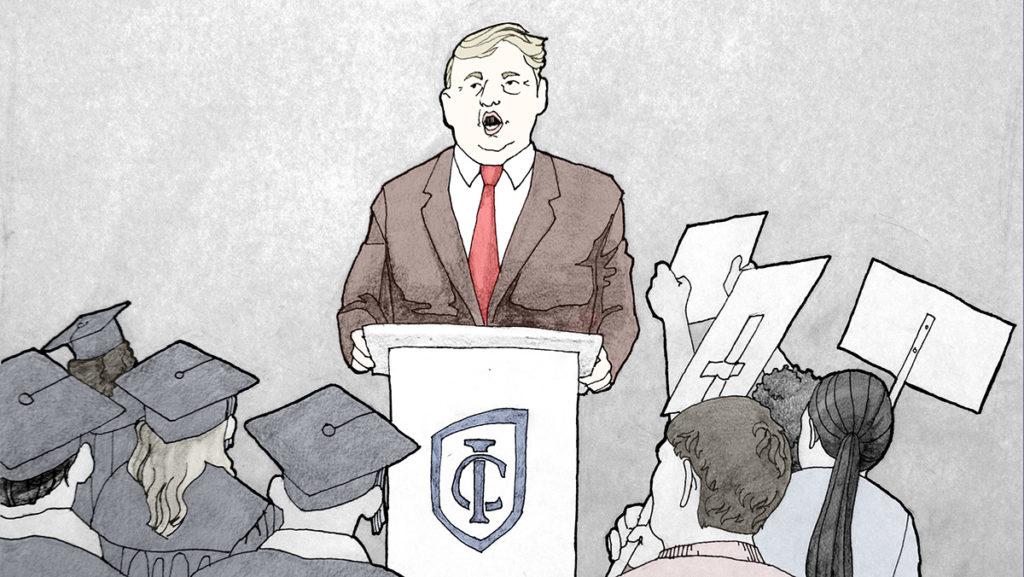

During Trump’s campaign, he captured his voters by appealing to their concerns about the current economy and political correctness, and by establishing a common enemy — elites who criticized his policies. This, along with tendencies toward anti-intellectualism, ties into how higher education may be affected by Trump’s election and how campus activists at Ithaca College and nationwide will continue to respond to Trump’s policies.

Higher Education Policies

From what he has discussed on the campaign trail, it appears Trump’s main mission is to reduce the federal government’s role in education — both at the K-12 level and in higher education.

Some of Trump’s proposed policies to address the student debt crisis include capping student-loan repayments at 12.5 percent of discretionary income, which is part of an income-based repayment plan, and taking the Department of Education out of the student-loan business.

DeVos’s stance on education is pro-charter and pro-voucher, and her primary focus is on the privatization of elementary and secondary schools, according to an article from The Chronicle of Higher Education. She and her husband, Richard DeVos Jr., have lobbied for school vouchers and charter schools and have spent millions of dollars supporting conservative issues.

Carlos Figueroa, assistant professor in the Ithaca College Department of Politics, said the appointment of DeVos as secretary of education is telling of how the Trump administration will act on education matters. He said he sees DeVos’s and Trump’s proposed policies for education as a continuation of a neoliberal environment in the United States, focusing on privatization and consumer choice.

“That automatically triggers an issue for me,” Figueroa said. “We’re perpetuating a consumer society … in terms of value-based engagement.”

Daniel Bonevac, professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Texas at Austin, said he disagrees with the opinion that Trump’s privatization education path is a bad one — it just has not been tried before.

“There are a lot of kids who fall through the cracks,” Bonevac said. … “For all sorts of reasons, it happens, which is why it’s not a problem easily solved,” “But to some extent, we need experimentation.”

One possible plan Trump has for education is to incentivize institutions to make “good faith” efforts to reduce tuition to receive federal tax breaks and tax dollars, according to CNBC. He said he will forgive student debt after 15 years, according to Time Inc.

One of DeVos’s possible plans, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education, could be changing the distribution of Pell Grants. Pell Grants offer up to $6,000 to 7 million students across the nation each year, the majority being in the bottom half of the income distribution. DeVos would most likely allow equal opportunity to Pell Grants for all, not just those from low-income families.

Mary Clare Reim, research associate of Domestic Policy Studies for the Heritage Foundation, said Trump’s ideas to decrease the federal government’s involvement in education reflects the will of the people to make their own decisions about how to educate their children — an ideology which would align with Trump’s appointment of DeVos.

As for Trump’s idea to take the Department of Education out of the federal loan process, Reim said this could help lower the rising price tag of colleges.

“Unfortunately, there is a lot of evidence that suggests that because of the federal government’s role in subsidizing higher education, it has led to higher tuition prices,” Reim said.

Reim said she would support the idea to let more students take private lender loans so that market competition could drive down rates.

Anti-Intellectualism and Trump’s campaign

The idea of anti-intellectualism played a significant role in the election of Trump. Historically, it has been defined as a hostility toward intellectuals and modern social and academic theories they endorse.

David Niose, legal director for the American Humanist Association, said he thinks that those who have an anti-intellectual mindset are not open to reason and strictly believe in actions and emotions when confronting reality — something he said Trump largely employed during his campaign.

Kyle Stewart, president of the Ithaca College Republicans, said he does not think people who are anti-intellectual are also anti-reason. He said that specifically during this election, many middle–class Americans have felt left behind by establishment politicians, many of whom went to very prestigious colleges and could be identified as elite intellectuals, so they voted for a candidate who promised change.

“People try to find some type of reason as to why they face economic difficulties,” Stewart said. “Sometimes, they see that reason as intellectuals who have college degrees, who have been successful and who are changing the economy away from industry towards economy that relies heavily on technology.”

One way Niose said he believes anti-intellectualism tied into this election was through fundamentalist religion. Eighty-one percent of white evangelicals voted for Trump, while 16 percent voted for Clinton, according to The Washington Post.

Bonevac said higher education itself could be blamed for the anti-intellectualism phenomenon. He said he has experienced firsthand how his own university has increasingly become more left-leaning over the 30 years he has been teaching there. He said if questions and lessons are only taught from one perspective, it is hard for professors to understand other political perspectives, which leads to the anti-intellectualist divide.

“I also think it’s important for intellectuals to speak out and engage with the broader society, to do things like explain their own views, but also listen back,” Bonevac said. “If it turns out that half the American public has the perspective that you consider wildly off–base, try to understand why.”

A transformation of college activism

Immediately following the election, protests erupted on college and university campuses across the nation. At Ithaca College, student-led demonstrations have been organized against Trump’s policies, and two campus activists, sophomores Talia Weindling and Shane Reynolds, have been heavily involved.

Reynolds said he is concerned for those who may not be able to attend school in the United States because of Trump’s rhetoric. Trump has proposed giving out fewer international visas to promote job opportunities for Americans and said he would place a temporary ban on Muslims entering the United States, which Reynolds said is a major concern of his.

“Definitely having a lot of friends who are Muslim or from other countries, it’s been hard for me to kind of see the fear in them,” Reynolds said.

He said he believes there is going to be more college activism with the Trump presidency.

Weindling said she thinks the growth of collegiate activism depends on the college’s environment. At the college, she said, she thinks it will most likely increase; however, she said, Ithaca is just one bubble. At the University of California, students protested in the streets and several students at American University burned the flag after the election. At Babson University, two students drove around in a pickup truck celebrating Trump’s victory.

Patricia Rodriguez, associate professor in the Department of Politics, said she thinks students are beginning to realize there are many issues that need greater attention due to Trump’s election.

Looking at the history of college activism, particularly civil rights protests on campuses in the 1960s, Rodriguez said she thinks today’s demonstrations and protests will mirror this decade. She said activism will be centered around different issues, and possibly different strategies, but that she hopes to see more of a connection between students and the communities in which they live.

“The connections between college and community are not that difficult to make — they’re both mobilizing, and that confluence, I think, will increasingly happen,” she said.