Last week, the Ithaca College community took part in remembering Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy. Keynote speaker Russell Rickford, associate professor in the Department of History at Cornell University, reminded students that the King celebrated today has been tamed and mythologized to “preserve the status quo, to mislead and pacify.”

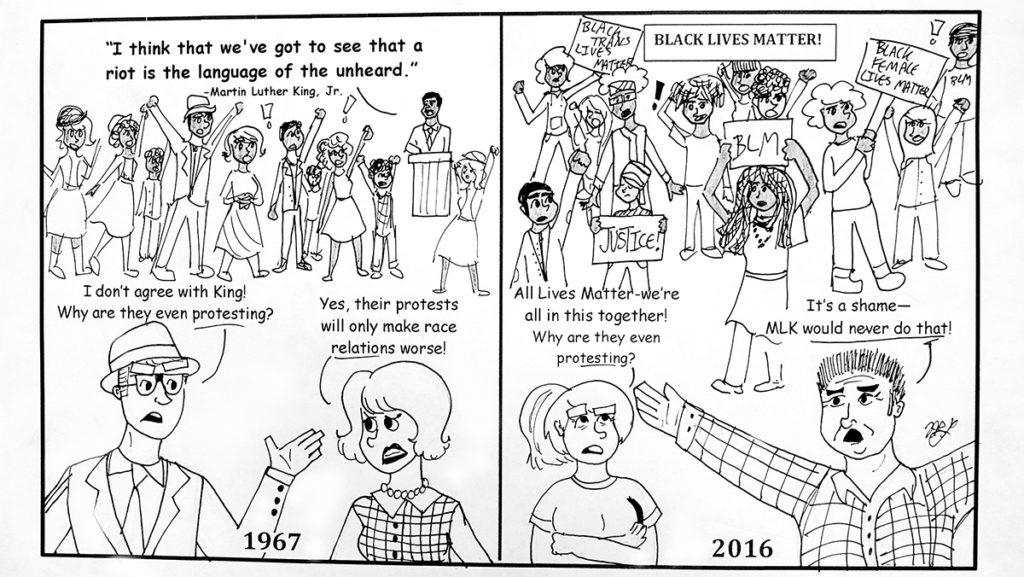

Rickford’s speech hits on a fact that much of white America fails to realize: The King celebrated on MLK Day is quite different from the King who existed decades ago. Over time, certain moments or quotes have been cherry-picked from history to create a whitewashed narrative that conveniently glosses over King’s core beliefs and radicalism, painting a picture that allows many white people to remain ignorant and complacent in discussions of systemic racism and oppression.

In the gaze of white America, King’s legacy starts and stops with his work in the Civil Rights Movement.

Most simply see King as a civil rights leader who preached nonviolence¹, even though King fought for more than just racial justice and recognized the value of rioting. In April 1967, a year before he was assassinated, King delivered the speech, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence,” where he strongly opposed U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War and said the U.S. was “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.”

And although King’s anti-war and anti-imperialism stances² are erased from his legacy — probably because his condemnation makes most white people uncomfortable — he remained adamant that this nation’s entrenchment in war overseas is a barrier to obtaining meaningful reforms for people in the U.S. This stance, along with his advocacy for economic justice and the creation of the Poor People’s Campaign, turned him into a threat to the status quo. In the years leading up to his death, King was relentlessly monitored by the FBI.

Many people are also quick to praise King’s nonviolence while simultaneously condemning the actions of the Black Lives Matter movement — a contradiction that ignores the relationship between the two. Black Lives Matter activists are continuing King’s fight for racial justice, and their focus on police violence and their methods of protesting do not make them any more radical than King himself. Criticizing protesters because of their methods of resistance plays into respectability politics and lacks understanding of why they are demonstrating in the first place³. It also shows that support of social justice causes is contingent on how comfortably a person can continue to live their life without any radical change4.

This “white moderate” is the person King warned was “the Negro’s great stumbling block toward freedom5.” Yet the fact that many white moderates idolize King while turning their backs on Black Lives Matter exposes the hypocrisy with which King’s life is celebrated today.

Primarily responsible for this distortion of King’s life are the years of U.S. history that have shoved this sanitary version of his legacy into the forefront. But teaching the Civil Rights Movement is fundamentally dishonest without fully discussing all of King’s work, not just the advocacy that is most appealing to the white moderate.

King’s message of racial and social justice cannot fully be understood nor appreciated through a whitewashing lens. Continuing to choose which parts of King’s life are palatable to white moderates is the antithesis to the fight for racial justice. Whatever white moderates choose to believe about King, the reality is that this country is far from achieving the racial, economic and social justice he fought for so adamantly.

¹ April 19, 1963. Letter from a Birmingham Jail: “Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue.”

² April 19, 1963. Letter from a Birmingham Jail: “Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.”

³ April 19, 1963. Letter from a Birmingham Jail: “But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. I am sure that none of you would want to rest content with the superficial kind of social analysis that deals merely with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes.”

4 April 19, 1963. Letter from a Birmingham Jail: “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed. Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct action campaign that was ‘well timed’ in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation. For years now I have heard the word ‘Wait!’ It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This ‘Wait’ has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that ‘justice too long delayed is justice denied.’”

5 April 19, 1963. Letter from a Birmingham Jail: “Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.”