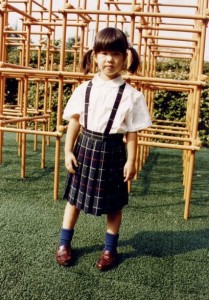

For her entire life, senior Cherrie Rhodes never knew anything but a diverse student population. She attended Seisen International School, an all-girls Catholic school located outside of Tokyo, for 14 years. Rhodes said she never had a problem with her mixed-race identity, half Japanese and half American, until she came to Ithaca College her freshman year.

“At my school, I think a third of my class was half Japanese and half white in some way,” she said. “I just never thought about it. And then I came here and people were like, ‘Have you ever had an identity crisis? Do you feel more Japanese or more American?’”

The U.S. Department of State currently provides assistance to 197 overseas schools through support programs to promote an American-style education program. Most of the schools are private and independent, and serve dependents of American citizens of the U.S. government abroad. Post World War II, many international schools were started for military families seeking an education for their children.

For the international student population at Ithaca College, many have had the opportunity for a mixed-culture education.

For example, a student born in Japan could go to a Japanese high school. Or like Rhodes, international students can attend an international school, or they can have the option to attend an international American school.

International schools provide a hybrid education. For example, students at international schools learn about social studies from all places.

Comparatively, international American schools teach a strictly American-based curriculum — students learn in depth about U.S. history. They also have more creative freedom within their classes and must be proficient in English upon arrival at the high school level.

Both international American schools and international schools require students to possess a passport from somewhere other than the school’s host country.

First-year physical therapy graduate student Jon Lin experienced some culture shock after arriving in the U.S.

Lin traveled to a completely new environment when he came to the college from the Taipei American School in Taipei, Taiwan. He said the line between the types of international students is fuzzy, but many students from these mixed-background educations can feel out of place, he said.

“When I came, I came to the international orientation because it was the last one right before I could move in so it was tough, because to [the college] I’m like any other kid,” Lin said. “I’m an American citizen, I speak fluent English, I went through the same educational system. But to my friends here, they think I’m an international student because I came from overseas.”

Diana Dimitrova, director of international services for the college’s Office of International Programs, said the office does not know much about those students other than what paperwork and visas they need to fill out. International students from English-speaking schools sometimes have a hard time defining their international status at the college, like Lin.

Lin said he feels Ithaca’s culture is what makes his American college education feel so much different from his American high school. He said though he went through an American education system, he spoke the Taiwanese language, ate Taiwanese food and enjoyed Taiwanese nightlife.

“When I was in Taiwan in school, once I left the school campus, it was a whole different world,” Lin said. “It was a different culture, different environment and a different language.”

Senior Romi Ezzo attended the American School of Kuwait. He said coming to Ithaca, he did not know a lot about current events because of Kuwait’s politics at the time of his education.

“In all of the atlases when I was in middle school, they would black out everything that said Israel,” he said. “Sometimes they would say Palestine, but other times they wouldn’t because they didn’t want to touch upon the issue.”

Senior Michael Kallgren attended the American School of the Hague in Wassenaar, Netherlands, for 10 years. Kallgren said ASH’s curriculum allowed him to learn basic subjects, like the States’ system does, to help him choose a focus in his classes later on.

“The nice thing was that in high school you were required to take both an introduction to U.S. history and an introduction to world history,” Kallgren said. “Then you could go into more specific things like European history and medieval European history.”

Many students who attend international or American international schools do so with the intent to return to the States for college. Lin said he knew attending TAS would help increase his chance of having a collegiate future in the U.S.

“I was born in the States, and then my family moved back to Taiwan,” Lin said. “They sent me to the American school because the whole point was for me to come back to the States for college.”

The college’s Office of Admissions tries to recruit international students from across the globe. Nicole Eversley Bradwell, associate director of admissions at the college, said the college’s reach to international schools is spread among all types of education. She and her colleagues attend fairs with other colleges to recruit students.

“We recruit students from national schools … as well as international schools, as well as American schools, as well as British schools, as well as any number of Canadian schools,” she said.

Rhodes said her perception of her own cultural identity hasn’t changed, but experiences different interactions with friends and family when she travels home to Japan for breaks.

“Increasingly, when I go home, people will try to speak English to me,” Rhodes said. “I try to tell them it’s OK, like, ‘I speak Japanese, I know exactly what you’re saying.’ It’s not like I’ve suddenly developed an American accent or anything. Maybe I carry myself differently? I don’t know, but it’s very strange.”