Amid the recent Trayvon Martin protests, racial relations sit on the forefront of American political discourse. But, according to documentary filmmaker and diversity educator Lee Mun Wah, the framework of the conversation remains skewed.

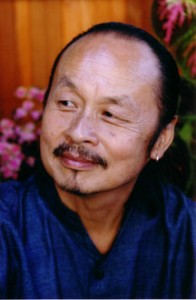

Tonight at 7 p.m. in Emerson Suites, Mun Wah will screen and lead a discussion on the role of race on campuses, based off of his most recent film, “If These Halls Could Talk,” which highlights 11 college students to examine racial relations in society and, more specifically, in the classroom.

Staff Writer Lucy Walker spoke with Mun Wah about his mother’s death, his films and the Republican presidential primary.

Lucy Walker: How did your childhood lead you to what you do now?

Lee Mun Wah: I grew up in a very poor neighborhood, so I was very used to living with a lot of different ethnicities. White people generally were there, but after a while, they moved off to the hills. What was interesting was all our schoolteachers were white, which was always my experience, so I didn’t see minorities as teachers or administrators. I became a filmmaker because I taught for about 25 years as a special ed. teacher in San Francisco.

One day in 1985, my mother was murdered. She was shot five times in the head by an African-American man. I mention about the African-American man because that was significant because my family and my father were pretty racist toward blacks. We knew this as kids, but it didn’t include me because I was working with black families. I always [thought] it was strange because, one, I was very close to my mother, and the other was because I was working with black families and black students. It seemed like a contradiction to me that it was just one person versus a whole group because my father wanted to instill in me that black people were very violent, which I think is still very prevalent today.

But the reason I was so traumatized by the event with my mom was because I was supposed to be at the house that day, and I was called away to a meeting. So, for a long time, almost three years, I blamed myself for not saving her. And then, eventually, I was so traumatized that I went into therapy, got a degree in counseling and then became a teenage therapist. I started working, specializing in individual violence. I eventually then worked with an Asian men group and a multicultural group dealing with anger, racism and leadership. One day, I decided just to film one of my Asian men, and then filmed my Asian men’s group, which was my first film, called “Stolen Ground.” That won many awards, and it’s like, “Oh, well, filming’s really easy,” so I did a film called “The Color of Fear,” and that’s where everything just took off.

LW: What are the main issues facing us in 2012?

LMW: I think that the issues of 2012 are as much as they were 50 or 100 years ago. The issues of race and racism are still alive and well today. The reason why I think we’re still at the celebratory stage is that we want to celebrate diversity, eat foods [and] wear clothing. But we still haven’t done the hard work, which [are] relationships. That is why we’re still struggling with issues of race and racism because we’re stuck at the wedding. Anyone in a really good relationship will tell you it takes work, [and] it takes practice.

In the United States, truthfully, the reason why we have this problem with issues of race and racism is because assimilation is not about assimilating who I am and honoring who I am in a nation made of ethnic groups. It’s really about accommodating to a white model, which continuously keeps wanting us to act white, talk white, be white. Then, all of the sudden, I’ll become “American.” No matter how many times I go through every day people saying to me, “My gosh, you speak such good English. Where were you born?” It’s a constant reminder to me that the only real American is white — that the words white, American, and human are all synonymous. … There’s nothing wrong with looking at color, but the reason why we don’t want to look at color is because it’s negative in this country.

LW: What solutions do you advocate for in regards to race?

LMW: I have a new article coming out, “I Am George Zimmerman, And So Are You,” that will be out in my next newsletter. What I mean by that is whether Trayvon Martin had a hood on or not, we still have it acculturated daily, in the media, books, films, conversations, that we still see black people, black men particularly, as dangerous. So I think when we begin to admit that to ourselves, when we begin to take a look at our stereotypes that we have. … I have to constantly be conscious of how those will affect my actions, my decisions, my relationships, my intimacy with people and how I view other people. We, as an audience, will start to look at how [we] are both racist and homophobic in this country. So all these issues, to me, we always keep them at arm’s length. There’s no real model about how to talk about this [and] how to bring it out into the open.