A baby–blue rusted sedan bursts from a small–town bank onto the street with a screech. Two men have just robbed a bank, yet no one’s chasing after them. In fact, no one’s coming for them at all. This is great news for the two men because they have no idea what they’re doing — they have no idea that this whole ordeal is right about blow out of proportion. “Hell or High Water” is one of the nine films nominated for best picture this year, and for good reason. It’s a tense and enjoyable Western with much to say about the current political and economic climate of the South.

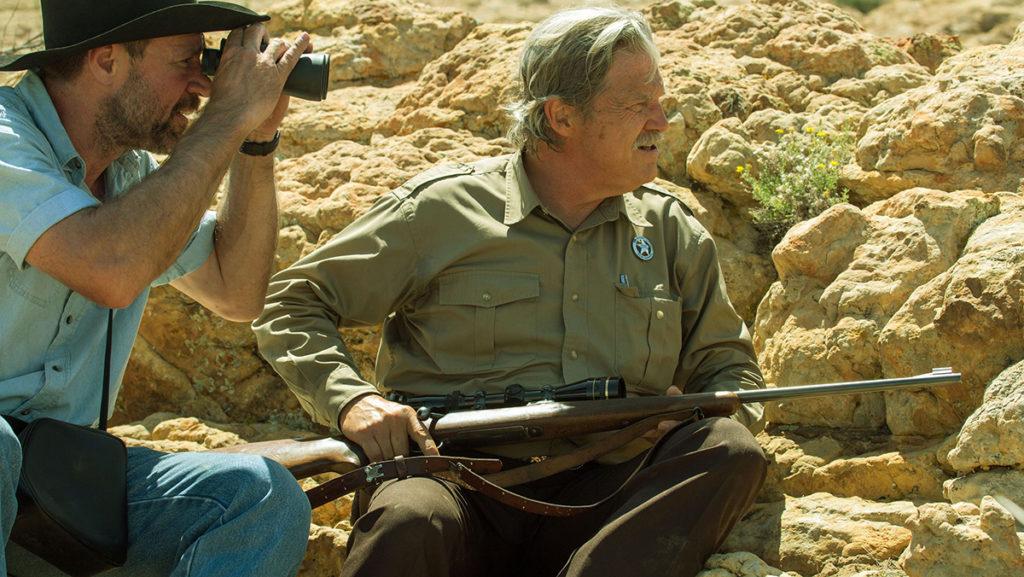

“Hell or High Water,” directed by David Mackenzie, stars Chris Pine and Ben Foster as Toby and Tanner Foster, respectively. They’re two small–town Texas men whose childhood home will be foreclosed upon if they don’t get a couple thousand dollars in the next three days. They can’t let go of the property because they have discovered it contains oil that could finally bring Toby’s family out of poverty. However, this puts them into conflict with the local sheriffs, Alberto (Gil Birmingham) and Marcus (Jeff Bridges). The ensuing piece is a film about the effects of desperation and the extent to which some men are willing to go for the betterment of their families.

The most immediate and striking feature of this movie is the landscape. Texas comes across as a desolate wasteland. “For Sale” signs litter what few businesses remain, surrounded by wide–open land that appears long since abandoned. It’s a world in ruin whose inhabitants want out. The only element of this land that isn’t in total disrepair is the banks. They loom over citizens like Big Brother, watching and exploiting the sad lives of these people barely hanging on. This helps justify the Foster brothers’ robberies and allows the audience to sympathize with all four main characters and dread their inevitable conflict.

The region and its people aren’t painted entirely as victims, however. Marcus, in particular, represents both the good and bad of his homeland. He’s a “good” man, but he constantly makes fun of his partner, Alberto, for being a Native American. He’s not trying to be rude — he actually cares for Alberto very much — but he always comes across as offensive and mean–spirited. As Alberto points out, what’s happening to white people is merely history repeating itself. White men drove the Native Americans off these lands, and now the world has moved on, allowing the banks to foreclose on the white man’s house and force him off the land.

The characters also shine through. Pine is wonderfully sympathetic as Toby, a caring and conscientious man only doing what he can to bring his family out of poverty. He clearly doesn’t want to be robbing banks, but it’s what’s necessary for his family’s future. Pine captures this inner conflict with ease. Foster is dangerous yet charismatic as his ex-con brother, Tanner. The sheriff officers are equally engaging. Bridges is captivating as Marcus, showing glimpses of charm and empathy under a grumpy and racist exterior. Birmingham plays the perfect nuanced foil to Marcus as Alberto. The majority of the movie is dedicated to slowly revealing these four characters through dialogue that shows how far they’ll go to do what they think is right.

The pacing is exceptional. Even though this movie spends the majority of its runtime on dialogue, it never feels plodding. One of the major ways this is accomplished is the steady reveal of back story and major plot points. The dialogue is fantastic throughout, painting portraits of deeply flawed yet compelling characters who feel all too real.

All of this steady building finally leads to a truly destructive third act. Without spoiling anything, this film takes a 180 turn from its small–town feel, careening into an ambitious and effective finish. Because the characters and world have been built up so well and feel so real, the whole affair ends up feeling far more visceral than most contemporary thrillers.

If this movie has one noticeable flaw it would certainly be its portrayal of women. Although the four male leads feel genuine and well–explored, there isn’t a female character with any real depth. The few women who are in this movie are hardly given any screen time or lines to speak of. As a result, none of them are given any nuance. The most egregious example in this movie is Toby’s ex-wife, Debbie. All the audience ever learns about this character is that she’s disillusioned because Toby hasn’t paid child support in a long time. That’s it. She’s one of the prime motivations for Toby, and she’s entirely glossed over. The other women who exist merely give some expository dialogue or add to the film’s general sense of devastation. It’s disappointing because this movie shows throughout that it can create enthralling characters, so the lack of representation of an entire gender is glaring.

While not doing anything entirely new for the genre, “Hell or High Water” remains a gritty and engaging drama with rich characters, thrilling action and thought-provoking themes of desperation and family, all on top of an admirably honest portrayal of the American South.

It may not win best picture, but it’s still a great film that’s well worth a watch.