Compared to today’s mainstream Western feminism, Islamic feminism is less discussed and less visible in feminist conversations.

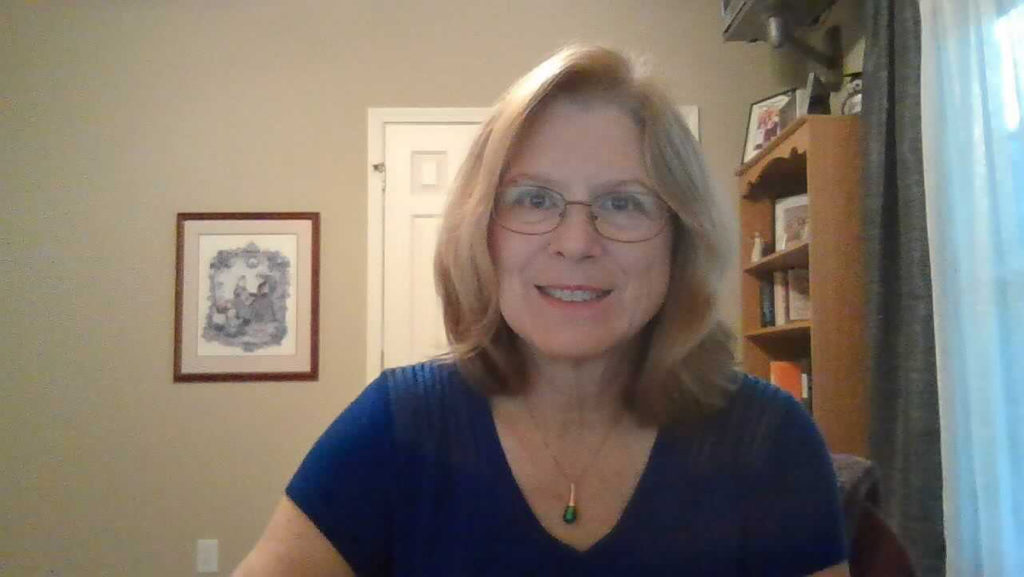

Shehnaz Haqqani, a Ph.D candidate at the University of Texas at Austin, gave a talk Feb. 28 at Ithaca College about Islamic feminism as part of the Women’s and Gender Studies Program’s Dissertation Diversity Fellowship. Haqqani spoke about the origins of Islamic feminism and its future in feminist discourse.

Opinion Editor Celisa Calacal spoke with Haqqani about the meaning of Islamic feminism, its goals and what Western feminism gets wrong about Islam.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Celisa Calacal: Could you describe Islamic feminism and what it means?

Shehnaz Haqqani: So Islamic feminism is a new movement. And it’s something that’s more modern as a part of the rest of the Western feminist movement or just feminism generally. And it’s a quest for gender equality and sexual justice — so gender justice — using Islamic sources and the Islamic historical tradition as a sort of root of gender equality in Islam.

CC: What makes it different from mainstream Western feminism?

SH: Certainly its emphasis on religion, its emphasis on Islam, its emphasis on the Quran, which is the holy scripture of Muslims. The idea is that, yeah, Western feminism or non-secular feminism or non-religious feminism might be helpful, might be one way of achieving gender equality or justice in society. But for Muslims who generally and universally uphold Islam … whatever they support or whatever they work for has to be rooted in Islam.

CC: What does Islamic feminism say about Muslim women wearing the hijab?

SH: So Islamic feminism — I am very careful not to speak of it as a monolithic term. We have multiple forms of Islamic feminism, just as we have multiple forms of feminism in general. Western, mainstream feminism has different waves, different forms of feminism. So Islamic feminism is like that as well. We have Muslim feminists, Muslim women who identify as feminists, Muslim men who identify as feminists who come in different shapes and sizes and who come from different belief systems. The one thing we have in common is that they’re Muslim, but they interpret Islam or the Quran very, very differently across the world. … I live in Austin, Texas, and here, Muslim women have a completely different approach to practicing Islam. So there’s no one way to answer that question. There’s no one rule that Islamic feminism practices on the hijab. But one thing that I would say that probably is standard at this point is there’s no oppression or there’s no compulsion in Islam from God. And so, when a woman does wear the hijab, she has to be respected for that choice — assuming it’s a choice. And if a woman is wearing it out of pressure, there are broader, larger factors, social/political factors that go into why women make the kind of choices we make. So if I meet a Muslim woman who identifies as a feminist who wears the hijab, I’m going to accept that. … Also, the more important thing is that Muslim feminists are actually not obsessed with the hijab. And this is a very Western thing, the obsession with the hijab. … So Muslim feminists challenge that by focusing on much more integral, much more serious, much more pressing concerns that Muslim women are facing. And the hijab is really not a concern for the most part.

CC: What are misconceptions about Islamic feminism?

SH: One of the most important things they get wrong is they imagine one way that Islam can let Muslim women practice Islam. … We don’t practice Islam the same way. We don’t have the same experiences because Islam or religions aren’t the ones that create experiences for the most part. What we experience is a product of a lot of other things — our class, our gender, our sexual orientation, the neighborhood, the kinds of politics. Those kinds of things play a much more important role than Islam. Islam doesn’t explain anything. Islam as a religion — Islam as a practice — doesn’t really explain much on why women are treated in a particular way. It’s politics for the most part. So I would say something the one thing people get wrong is they assume … that there is such a thing as what Islam says about women or what Muslim women think or what Muslim women experience. There’s just no such thing. It’s so much more complicated than that.

CC: What do you want people to take away from your talk?

SH: One is that the kind of struggles that Muslim feminists are facing, Muslim feminist scholars, Muslim women who are feminists and just Muslim women in general … they’re a part of many, many other issues that women, Muslim women and non-Muslim women are facing generally. … Islamic feminism is a part of a larger conversation on gender and on feminism and on religion. So one of the most important things that I really hope people will get out of this is that one of the struggles that Muslim feminists are facing … is that … we’re trying to fight misogyny within our own community. We’re trying to fight misogyny and fight the … practices of Islam that are still rooted in history. But they are not exclusive to Islam. … These practices are common to other faiths as well, and they’re still common to other faiths. But the focus on Islam and the focus on patriarchy only in Islam is a political issue. And so Islam generally is perceived as this very, very misogynistic religion because it’s one of the main enemies of the West, right? The West has perceived it as an enemy. And so then, it makes sense to present a lot of patriarchy in Islam. … But at the same time, it doesn’t help that we face so much rejection from other feminists. … Christian feminism, Jewish feminism, Hindu feminism — there are also these movements that are currently going on, and Islamic feminism is a part of those movements. And we face rejection from different kinds of feminists and different kinds of feminism because of this political assumption … that Islam is inherently against women and therefore Islamic feminism is an oxymoron.