Going to college is heralded as the gateway to a better life, to a well-paying job living in a nice house in a well-off, middle- to upper-class neighborhood. College is and always has been advertised as a ticket to improvement.

But the reality is far different. This week, The Ithacan explored the intersections between class and higher education and found that postsecondary learning and the benefits that accompany a college degree are disproportionately further out of reach for many low-income families. The problem is institutional and the impact is staggering, creating an environment that advantages those who can afford the top price tags while lower-income families get left miles behind the finish line.

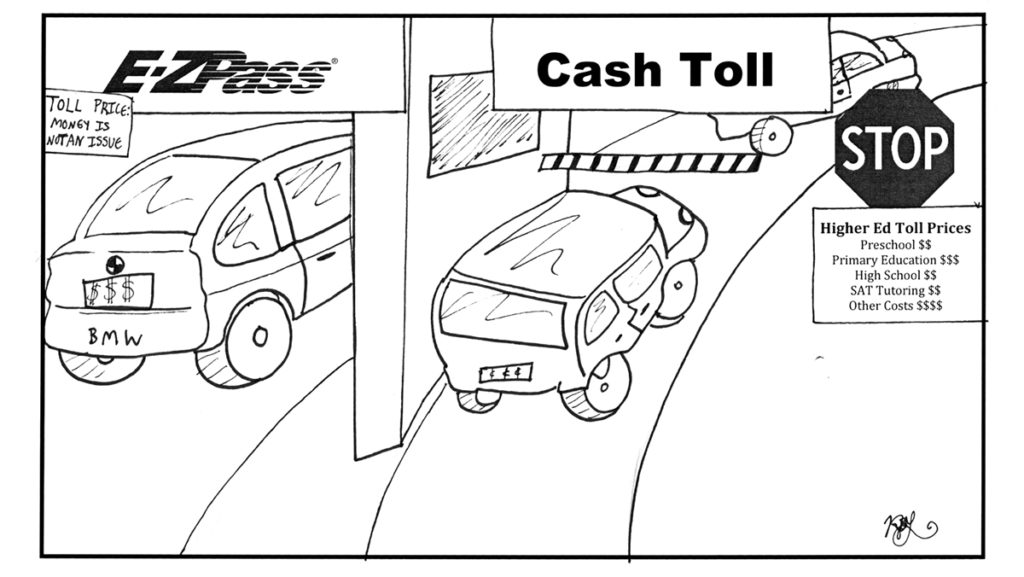

Skyrocketing tuition prices are not the only barriers preventing low-income families from accessing a degree. The very growth in prestige surrounding college has cultivated an economic industry dedicated to putting people on the path to college starting in primary school and continuing on through high school. College readiness programs developed to place kids into the most prestigious colleges. SAT, ACT and Advanced Placement preparatory classes tutor teenagers to get high scores on standardized tests to make them more competitive in college admissions. Yet these extra programs come with a heavy price tag, meaning they are available only to those families who can afford to shell out extra money to pay for their children’s future success.

The competitiveness of college has also created a hierarchy in the high school system in which well-endowed high schools provide the resources necessary — AP classes, SAT tutoring, honors classes, college-prep courses — for its students to have better access to higher education. It creates an educational pipeline in which students who are in a position to attend good high schools — whether through having the financial means to attend expensive private schools or by virtue of living in districts that can support the development of high-quality public schools — can transition to college, thus shutting out students who attend economically disadvantaged public high schools and do not have access to these educational resources.

In reality, the road to college is marred with institutional obstacles, with roadblocks that are more likely to stall low-income families or drive them off the road completely.

Restricting the accessibility of college only perpetuates an insidious cycle of income inequality, making it ever more difficult for families to achieve the fabled dream of social and economic mobility. Students of color are also disadvantaged by this system, as students of color are more likely to come from lower-class backgrounds. Not only do colleges become economically homogeneous, but racially homogeneous as well, reflecting a history of systemic discrimination that places people of color paces behind white people. The stark whiteness seen in government, the media and business industries did not come about by accident but instead was produced as a result of the economic and racial homogeneity of higher education.

It’s a cycle that places the finish line of college further and further away from the initial starting point.

These problems do not stop once students get into college, either. Here at Ithaca College, for instance, it is well-known that the college is not equipped to adequately address the needs of students from marginalized backgrounds, whether in race, sexual identity or economic status. The results of this are reflected in the college’s recent campus-climate survey, which shows that students of color, first-generation students, LGBTQ-identifying students and low-income students continue to face obstacles once they enter the gates of higher education. This environment at the college is a microcosm of higher education as a whole. It is indicative of a system that not only disadvantages marginalized students from the beginning but continues to be unwelcoming, even when these students do manage to enter college, making them feel like they did not belong in these institutions in the first place.

In the past few decades, colleges have become bastions of economic privilege in which middle- to upper-class families are the dominating face of higher education. Pretending otherwise, that higher education is accessible to all and does not privilege one economic class over another, displays willful ignorance toward an issue that impacts millions across the country.

This is the aspect of diversity that often gets shoved under the rug in higher education. While administrators are quick to tout racial diversity at their institutions, they are often mute when it comes to economic diversification. Most colleges do not even include economic status in their demographics reports. But one form of diversity should not come at the expense of another. Addressing this problem cannot come in the form of quick Band-Aid solutions — it is a systemic issue that can only be fixed through foundational solutions. It involves solutions on every level: local, state, federal, public and private. For as long as higher education continues to cost more than many families can handle, it can never become the true gateway to financial and economic success it was ideally meant to be.