While some students will be working at internships related to their college majors this summer, Ithaca College sophomore Ian Sawyer will likely be working in a service or office job. He cannot afford to participate in an unpaid internship or even move to a more urban location where there might be paid internships.

Sawyer said he pays for his $13,000 of college tuition by taking out student loans and working 60 hours a week on average during the summers. There’s no time for an internship that might offer insufficient or no pay.

“There’s just no way I would be able to,” he said. “I would have to work 60 hours a week and then do an internship on top of it.”

Sawyer also lives in an area where few paid internships are offered, so he would have to pay for his own housing and groceries if he moved elsewhere, something he cannot afford.

Employers are increasingly looking for students who have completed internships, heightening the competition to find them — particularly ones that are paid. The remaining unpaid internships leave behind lower-income students who cannot afford to work for free.

While the federal government does not keep track of data about the internship economy, current estimates say that between 500,000 and 1 million people participate in unpaid internships every year in the U.S. According to a study by the National Association of Colleges and Employers, over half of graduating college seniors in 2012 participated in some type of internship during college. This is almost double the rate of students participating in internships found by a study two decades ago, according to the same study. However, students from higher socioeconomic classes are better able to participate in unpaid internships because they can afford to work for free, leaving lower-income students behind and often perpetuating wealth inequality.

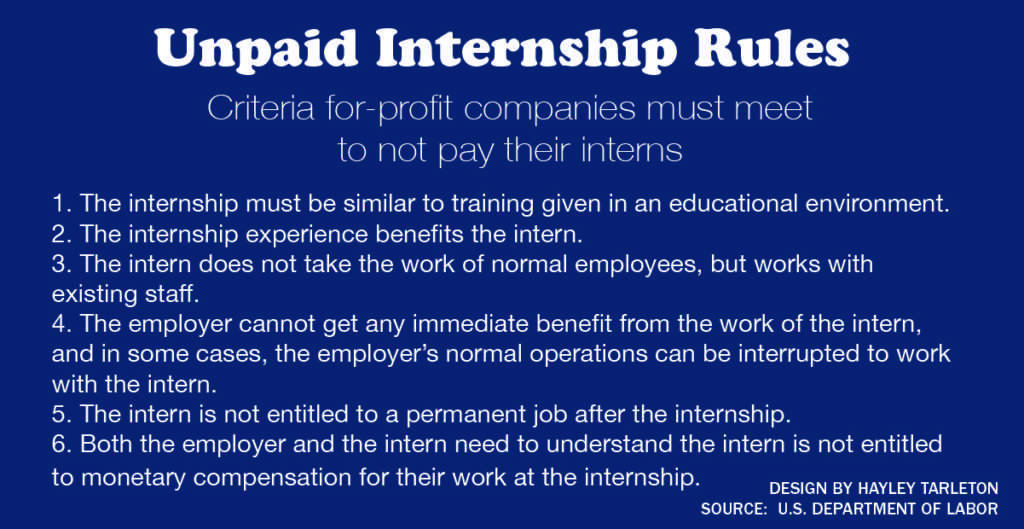

In 2010, the U.S. Department of Labor issued a fact sheet that outlined the criteria employers from for-profit companies must meet to be exempt from paying interns minimum wage, or anything at all. These criteria include the following: The internship must have educational aspects to it, it must allow students to work with existing staff at the company, the employer cannot get advantages from the intern’s work, and the internship must be for the benefit of the intern. The fact sheet further explains the importance of whether interns are providing some kind of benefit to the company. The intern must be getting more of a benefit than the company for them not to receive pay.

Nonprofits and government organizations are not legally required to pay interns. There have recently been a number of lawsuits challenging the practice of unpaid internships under the Fair Labor Standards Act. These lawsuits have led to a group of varied court decisions. In a particularly well-known case in 2011, two unpaid interns who worked on the set of “Black Swan” sued Fox Searchlight Studios, saying the company violated minimum–wage laws by not paying them. Five years later, in 2016, a settlement was reached that compensated the interns $495 each for most, and between $3,500 and $7,500 for the lead plaintiffs in the case. Following this lawsuit were similar cases where unpaid interns sued multiple large corporations, including NBC, Warner Music Group and Viacom. These companies also came to multimillion-dollar settlements, requiring them to pay their former interns.

David Yamada, professor of law at Suffolk University and director of the New Workplace Institute blog of news and commentary about work and employment relations, said unpaid internships often require students to pay for academic credit for their degrees to show the interns are benefiting from the internship and justify not paying them. The academic credit is supposed to signify educational gain — thus, a benefit that exempts the company from paying the intern minimum wage.

This practice often holds students back financially, Yamada said.

“There’s a double whammy here for students,” he said. “In essence, what you’re doing is you’re paying tuition to work for free.”

However, unpaid interns often provide some kind of work that benefits the company and therefore break this law, said Dan Crawford, media relations director for the Economic Policy Institute, a think tank created to include low- and middle-income citizens in policy discussions.

High-income students already benefit the most from these policies because they are able to afford experiential and resume-builder opportunities regardless of whether they pay, Yamada said, advancing growth in wealth inequality.

“It’s going to be students who disproportionately come from backgrounds where somebody is going to subsidize that summer for them,” he said. “It’s not any criticism of those students, but it leaves out in the dust students who look at the opportunity and conclude they don’t have the means to be able to work for free.”

Sawyer is an English major, and after graduation, he is planning on attending graduate school and becoming an English teacher. He said he looked into a few paid internships related to his major, but because most paid internships pay minimum wage, he said he would not make enough money.

“I need to make the maximum money I can,” he said.

In addition to unpaid internships’ excluding students from lower socioeconomic classes, research has shown that they also hold students back in their futures. According to a study by the National Association of Colleges and Employers, students who participated in paid internships during college were more likely to get a full time–employment offer after graduation than those who participated in unpaid internships. The study also found that students who do paid internships have higher salary offers coming out of college than students who participated in unpaid internships.

Mimi Collins, press and publications staff member at NACE, said one reason for the higher employment chances for paid interns is that often, the main goal of for-profit companies’ having paid internships is to find people to hire.

“They’re using their internship programs to identify people that they want to hire for full–time positions,” she said. “It’s kind of a test drive.”

Collins said the primary purpose of unpaid internships is for students to confirm an interest in a field, not to find employment.

Crawford said these data make sense because if an employer looks at a resume with many unpaid internships on it, they will see a person who is willing to work for less money.

Unpaid internships can also be difficult for students who receive high financial aid packages, even full scholarships. Senior Kelli Kyle is a rising junior Park Scholar and has had a full-tuition scholarship for her junior and senior years. Kyle said she worked as an unpaid intern at KCET, a public TV station located in southern California, through the Park Center for Independent Media last summer. Kyle received a stipend from the PCIM, but it was not enough to support her, so her parents had to help. She said she would not have been able to get the experience she received without this assistance from her parents.

Kyle said she interned from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. three days a week and had a side job two days a week at the Salvation Army as a digital operations assistant for its Western locations. She said she would have interned for more days if it were paid but that she needed to have a source of income. Kyle said it was exhausting for her because she was working a full week but only getting paid for two days.

“I was getting a great experience, but it’s just stressful when you have to worry about how much are my groceries, how much is gas, how am I going to pay for activities on the weekends, things like that,” she said. “It was me struggling to give 100 percent when I was being stretched so thin because I had to survive in LA.”

Kyle said the stipend from the PCIM was helpful to offset the costs but that most of it went toward the credits required for the grant. And she still needed to pay for lodging and groceries.

“While it was helpful, it’s never everything,” she said. “And not to sound ungrateful — because I’m very grateful that I received that — but, you know, there’s just challenges that happen when you’re working three days a week and not getting paid for it.”

Sawyer said he might be able to participate in an unpaid internship if he were not attending a college as expensive as Ithaca College.

“It would be one thing if I was going to a state school, and if I was to take the summer off and take out a little bit extra of a loan,” he said. “But I’m taking $5,000–6,000 of loans a year, and my bank account is close to empty now. … It sucks, but it is what it is.”

Unpaid interns can sometimes face more than just monetary insecurity in their positions. Yamada has also done research on whether or not unpaid interns are entitled under anti-discrimination laws and civil right statutes for employees. Yamada said in his research that most unpaid interns are not covered under anti-discrimination and sexual harassment laws because they do not meet the requirements of employee status due to their lack of compensation.

“There’s a real gap in the law there, especially at the federal level, that I think is very disturbing,” he said.

Yamada said he has seen an increase of unpaid internships’ being catered toward students who have completed their undergraduate and even graduate degrees because employers see they can get free labor at entry–level positions designed for people with degrees.

“I think for me, the troubling thing is there’s sort of a slippery slope here,” he said. “How deep into one’s vocational or professional life do we have to go to find a decent entry-level paid job when the unpaid work keeps proliferating?”

Bryan Roberts, associate dean in the Roy H. Park School of Communications, said the dean’s office is constantly talking about how they can help students in finding paid internships and assisting those in completing unpaid internships.

“It hurts everybody,” he said. “You have to make a lot of money or have a family with a lot of money to really not work.”

To assist students doing unpaid internships, many colleges offer students scholarships. Ithaca College offers a few scholarships for students to help pay for the costs of unpaid internships.

The Park School offers the Big Apple Award — worth $1,500 — for three students who are participating in internships for credit in the New York City area. The Park School also offers the James B. Pendleton Award to cinema, photography and media arts majors; television majors; and emerging media majors who are completing a summer internship for credit. The maximum award amount is $1,000 and is based on academic and creative achievements. The Office of the Provost offers an award called the Emerson Summer Internship Award of up to $3,000 to seniors at the college who display financial need.

Two scholarships are offered through the Office of Career Services: The Class of 2008 Scholarship is for current freshman, sophomore or junior students who have an unpaid internship, and the Washington, D.C. Scholarship is awarded to current freshman, sophomore or junior students who have a paid or unpaid internship in the D.C. area.

Danielle Young, career counselor in the Office of Career Services, said the awards vary each year but range from $500 to $1,200 for the Class of 2008 Scholarship and $500 to $1,600 for the Washington, D.C. Scholarship. Young said that if multiple awards are given, students could expect a minimum of $500.

“Some money is better than no money, so even if you get $500 and that helps pay for your food … that’s something that you don’t have to come up with out of your pocket,” Young said.

Applications for these scholarships tend to be low, Young said. Many students do not know about the scholarships career services offers or don’t think the scholarships offer enough.

“Not a lot of students know about the opportunity or are taking advantage of it. This year, we had 17 applicants for the Class of 2008 Scholarship,” Young said. “We got even fewer for the application for the Washington, D.C. Scholarship. There were only four applicants.”

Young said career services also helps students secure an internship by assisting with resumes and interviews. When it comes to housing, career services does not place students in a particular area — the career counselors can only advise students where to live, Young said.

The PCIM places students at various independent media institutions and advocacy nonprofits across the country, according to its website. The stipends granted by the PCIM, like the one Kyle received, range from $1,600 to $2,850. To receive these scholarships, students must pay for credit, and the cost per credit for Summer 2017 is $1,254.

Jeff Cohen, director of the PCIM and associate professor in the Department of Journalism, said the stipends assist many students but that the program is not an option for students who need to work the entire summer.

“It’s because we give them $2,800, and they have to pay $1,200 for credit, and they only clear $1,600, it may not be enough for some students,” he said. “Let’s face it: Some students have to work and make a real income, more than $1,600 for three months.”

Kyle said the credits she had to pay for were ones she did not even need for her degree.

“I have no reason for it, no purpose … not required for my degree, yet I paid X amount of dollars to have it,” she said. “So it’s like, ‘What am I paying for?’ … I’m paying $1,800, and I’m not using it, so that was the biggest frustration I had.”

Other institutions similar to the college have awards to give to students who have acquired an unpaid internship. Providence College, for example, offers about 5 students a year an award of $4,000.

Laura Pellecchia, associate director of the Center for Career Education and Professional Development at Providence College, said this is the second year the award is being offered to students. The requirements for the award are not based on financial need, and the internship does not need to be for academic credit, but it must be through a nonprofit organization. Pellecchia said she thinks the sum given to students is enough for students who will be working an unpaid internship. Applicants who receive the awards are only eligible to receive funding from the program once.

Other institutions do not offer their students any grants. Siena College does not offer any type of award or grants to students who have obtained an internship.

Ashley Dwyer, assistant director for employer relations at Siena College, said the college does not provide students with stipends because it is up to the company to decide if students are paid.

“If a student is pursuing an internship with a specific company, it would really be up to the company to decide if they’re going to be paid for that experience or provide a scholarship or stipend or not,” she said. “They’re not working for us. They’re working for the company. So why would we give them an award when they’re not working for us? Unless they’re working for Siena College.”

Yamada said that until the issues are defined more decisively by the law, there will be legal gray areas determining in what situations interns are required to be paid.

“The current state of the law gives employers some incentives to start with unpaid internships and then sort of dare someone to sue them,” he said.

Sawyer said that because these internships are unpaid and students often have to spend money on housing and paying for credit, lower–income students are often left behind.

“It just kind of reinforces the cycle of disenfranchising those who are poor economically.”