Junior Gillian Friebis said she usually does not speak in class, but that when she decided to raise her hand one day in her politics course, she was shut down by a man in the class. It was an experience she feared would occur after seeing other women being interrupted in the same fashion by other men.

During a class discussion about the political relationship between Catalonia and Spain, Friebis spoke only to be immediately and repeatedly interrupted by a man who said he was trying to play the devil’s advocate to her point.

“After he kept talking over me, I didn’t keep trying, because I knew it was going to happen again, and it reminded me, ‘Oh yeah, this is why I don’t talk in this class,’” Friebis said.

Women at Ithaca College, like Friebis, said they have experienced and witnessed similar scenarios in their classrooms where women’s thoughts are disregarded, shut down, re-explained and interrupted by men, and in some cases, male professors. Friebis’ experience is an example of sexist behavior in the classroom, which is commonly dubbed as “mansplaining:” when a man comments on or explains something to a woman in a condescending, overconfident and often inaccurate or oversimplified manner, according to Dictionary.com. While mansplaining is one form of sexist behavior in the classroom, men interrupting women and re-explaining their thoughts also reinforces societal gender hierarchies.

Student experience

Men in sophomore Brooke Maybee’s politics class, Food and Water: Challenges to Sustainability Politics, taught by Juan Arroyo, assistant professor in the Department of Politics, would aggressively argue with her in the class, she said. Maybee said this made her question her intelligence and her willingness to participate.

“The way they dominated the conversation made me feel like I was excluded,” Maybee said. “It was hard to get a word in and, in that way, I felt that I couldn’t be part of that conversation.”

Her experiences discouraged her from taking any more politics courses, she said.

“I know I’ll never be comfortable taking a politics class again, even though in high school I loved politics,” Maybee said. “It was just horrible because I didn’t feel comfortable, and I didn’t feel like I knew anything even though I definitely did. I felt invalidated.”

Arroyo said he notices that most students, in general, are not very active participants in class, and men are usually more willing to talk than women. Additionally, he said if he sees women making facial expressions which show they are engaged in the conversation or know a woman has intelligent things to say from papers and assignments, he will call on them to include more voices.

Junior Sam Castonguay said she also experienced mansplaining while participating in the college’s DANA Student Internship Program during the summer of 2016. For the program, Castonguay, a sociology major, was paired with a faculty member on campus to do a paid, long-term research project where, she said, she developed a thesis about female fanaticism with boy bands like One Direction. She said she and another woman psychology student were paired up with two mathematics students who are men to critique each other’s research, but rather than critiquing, she said that the two men mansplained why they believed her research was unimportant.

She said the men told her things like ‘I don’t really understand the point of this study at all,’ and ‘You should look at this instead,’ which she said frustrated and degraded her.

“I spent four months doing preliminary research into this topic, and I didn’t even get to defend myself in that moment because I was so taken back,” Castonguay said.

She said this experience still affects her ability to participate and give research presentations.

“I still remember that experience vividly, and I was deterred from doing any of those events,” Castonguay said. “It really put a damper on the opportunities I felt comfortable taking advantage of.”

Similarly, senior Stephanie LaBatt said she experiences mansplaining frequently in group project settings. She said that once in her Corporate Communications class, she was paired with two other women and one man to make a presentation for a company. She said the man did the entire project without accepting any suggestions from the women because he thought he had more experience. She and the other women were offended, LaBatt said.

“He would say no to everything we said and took charge,” LaBatt said. “He would say, ‘I’ve done this,’ ‘I have this experience, this internship,’ and this and this, and you guys don’t… We just let him do it. There was no point.”

The origin of mansplaining and surrounding research

Rebecca Solnit, a writer, is credited with coining the term “mansplain” in an anecdotal and research-based essay she wrote in 2008 called “Men Explain Things to Me.” Shortly after, dictionaries such as Oxford, Merriam-Webster and Dictionary.com, made it an official term.

Solnit said in an article for The Washington Post that she wanted the term to be a concrete way to describe a woman’s experience in a way that is more powerful than the terminology typically used to describe sexist behavior such as ‘patronizing.’ Her work emphasizes the effects of silencing people, particularly women, as a form of oppression.

Friebis said she notices men taking up a lot of space during discussions in her Introduction to U.S. Politics class taught by Alexander Moon, assistant professor in the Department of Politics. She said men often argue and make comments that do not pertain to the course readings or class discussions, and she said she feels that the men are given more latitude by other students to make such commentary compared with women.

“A lot of times I don’t pay attention because people just argue the whole time, and there’s nothing I gain out of that,” Friebis said. “Sometimes when people make intelligent arguments and make counter-points, I am like, ‘oh okay!’ I tend to sit there respectfully and nod to show people I am listening, but they don’t give me that same respect.”

Moon said he notices that men speak more than women in class, but he said that he does not think mansplaining is a dominant force in his classrooms.

“I do notice that, on average, men are more likely to talk than women, and I imagine some people identify that as mansplaining,” Moon said. “I try to make sure everybody speaks, regardless of gender. I am very cognizant of the gender dynamic in class discussions.”

Additionally, junior Alyssa Curtis said she and other women often experienced mansplaining in her Journalism History class that she took during Spring 2017 with Todd Schack, associate professor in the Department of Journalism.

“Anytime we would talk about something, they would interrupt to say pretty much the exact same thing we were saying or even what the professor was saying, adding nothing to the conversation, all the time,” Curtis said.

She said Schack sometimes acknowledged when this occurred and tried to move on to the next topic.

Schack did not respond to a request for comment.

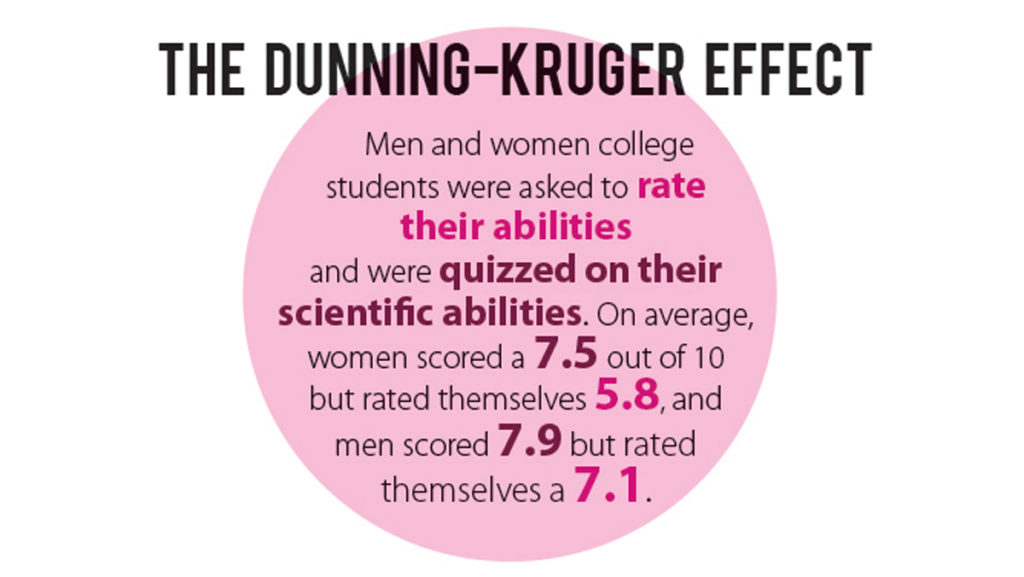

A study by David Dunning, retired professor in the Department of Psychology at Cornell University, and Joyce Ehrlinger, assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at Washington State University, analyzes the relationship between female confidence and competence found that women are less assured in their abilities than men, who tend to overestimate their abilities.

In the study, men and women who are college students were asked to rate their abilities and were quizzed on their scientific abilities. On average, women scored a 7.5 out of 10 but rated themselves at 5.8, and men scored 7.9 but rated themselves a 7.1. Their actual performances were almost the same. The research suggests the scoring disparities occur because men are more confident in their abilities than women.

Dunning said classrooms may lack intelligent conversations when only some students constantly speak.

“You don’t get a wide range of ideas and thoughts being said because the air is being filled with things people say that are willing to talk, but, it might be banal,” Dunning said. “What you want is to get the most people you can talking. It’s not good when one person talks, including the professor.”

Additionally, Cameron Anderson, professor at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, conducted research on overconfidence. His research found that people who speak with confidence tend to be admired and listened to more, and as a result, the competency of a comment is irrelevant in a discussion or meeting setting if one speaks with confidence.

“The bad news is, if you’re in an environment where you see people gain attention and influence simply because they are highly confident — even if they aren’t the most competent — it’s going to signal to other people that confidence, rather than actual competence, is important,” Anderson said via email.

Research by gender equity scholars David and Myra Sadker, who published their first study “Sexism in the Classroom: From Grade School to Graduate School” in 1986, found that typically in classrooms, boys received more positive reinforcement, received more attention, were asked more complex questions and were praised more for their “academic acumen,” whereas girls were praised for social skills and docility. The study was conducted in 100 classrooms across four states.

Sophomore Jack Gaffney said he often witnesses other men mansplaining to women in his Argumentation and Debate class he is taking this semester.

“There’s a ton of guys who do it,” Gaffney said. “It just seems ignorant.”

Gaffney said he is probably guilty of interrupting women, too, and he thinks it occurs because of social conditioning that teaches men how to interact with women.

Sophomore Luke Miller said he notices women being shut down and ignored more in small group settings in many of his classes. He takes Argumentation and Debate with Gaffney and said he also notices other men in the class interrupting women.

Sophomore Graham Klimasewski said men, including himself, are often oblivious when mansplaining and sexist behaviors occur in class.

“I don’t really notice it in class, but I am pretty oblivious to it,” Klimasewski said. “I interrupt a lot, and recently I noticed I do it more to girls. That’s not what I would call mansplaining, but it’s an issue I am addressing.”

He also said he thinks he does this as a result of societal norms and conditioning.

Correcting mansplaining at Ithaca College

Students say professors could handle mansplaining by identifying and shutting it down when it occurs. Senior Sloane Kazim said Hadley Smith, retired assistant professor in the Department of Writing, helped to defuse a situation of mansplaining that arose in their argument class in Fall 2015.

During a class-wide critique of their thesis paper, Kazim said a man told them that their argument — that the gender binary is harmful — was invalid and rooted in ‘Tumblr logic.’ ‘Tumblr logic’ is a condescending term used to describe millennial bloggers who use the social media app Tumblr and are viewed as nonsensically liberal.

Kazim said the professor rebutted the man, which prevented him from discrediting their argument.

“Many people in the class, especially when he made the comment about ‘Tumblr logic,’ rolled our eyes because it was obvious it wouldn’t be anything academic-based,” Kazim said. “It was just some dude airing his grievances.”

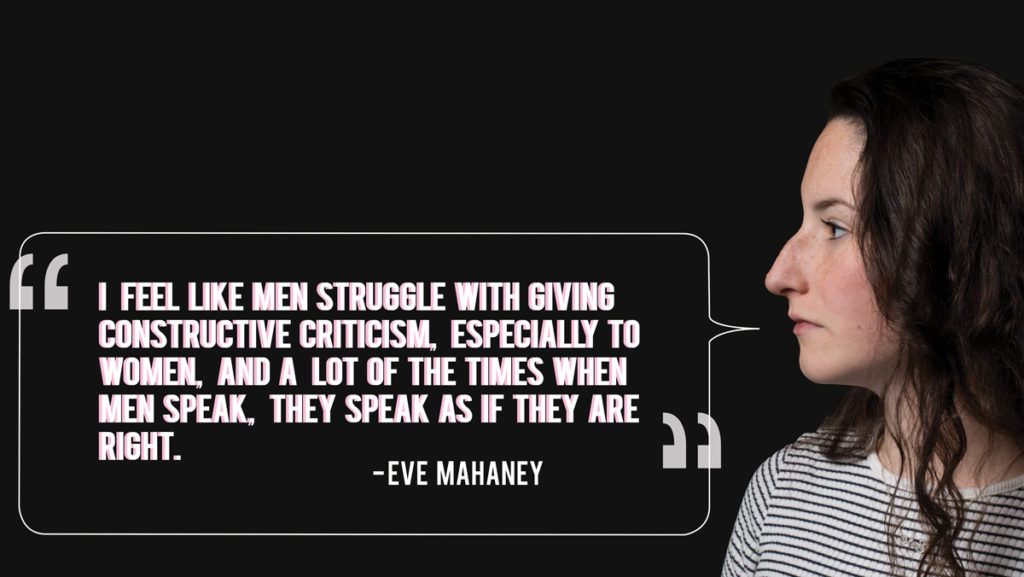

Senior Eve Mahaney said that in her Large Format Photography class with Rhonda Vanover, assistant professor from the Department of Cinema and Photography, men often would critique her, and other women’s photos, in unconstructive and demeaning manners.

“I feel like men struggle with giving constructive criticism, especially to women, and a lot of the times when men speak, they speak as if they are right,” Mahaney said.

She said Vanover handled these situations well and would call men, and women, out when they were not speaking constructively.

Vanover said via email she notices men dominating her classroom discussions and critiques, which she said tends to silence women. She said photography is subjective and it is challenging to critique one another, but she said students miss out when only vocal students talk and others feel silenced.

“I think it’s important that men and women participate equally in the classroom because each have something unique to contribute,” Vanover said. “From time to time, however, I notice men dominating classroom discussion and critique. When this happens, women tend to become very quiet, and it’s difficult to maintain representative points of view.”

Castonguay said she wants more awareness and training, particularly for professors, surrounding mansplaining, so they can defuse situations that arise in class.

“I would really just like these individuals to be aware of it,” Castonguay said. “Especially for educators, so they know how and when to intervene.”

Peyi Soyinka-Airewele, professor and chair in the Department of Politics, said via email that this is an issue the politics department had discussed at the end of the 2016–17 academic year at a department dinner. The faculty acknowledged that gendered power dynamics are present in politics classes, which create distinctive speaking patterns where some voices are always heard and others are silenced.

Female students in the politics department shared their experiences at the dinner, which Soyinka-Airewele said was helpful for the staff. She said the department has had preliminary discussions about what they notice in their classrooms and have brainstormed how to identify and address problematic gender dynamics.

“When a classroom has vibrant discussions, it is easy to ignore how gendered patterns in that space may marginalize and devalue some students,” Soyinka-Airewele said. “This is a continuing problem in U.S. academics, as well as in the corporate and political spheres. We have to continue to excavate, confront and eliminate the attitudes and practices that underlie these disempowering experiences.”