Laura Muscalu, lecturer in the Department of Psychology, spent her time in graduate school wondering what goes on in the brain when a bilingual person tries to juggle multiple languages.

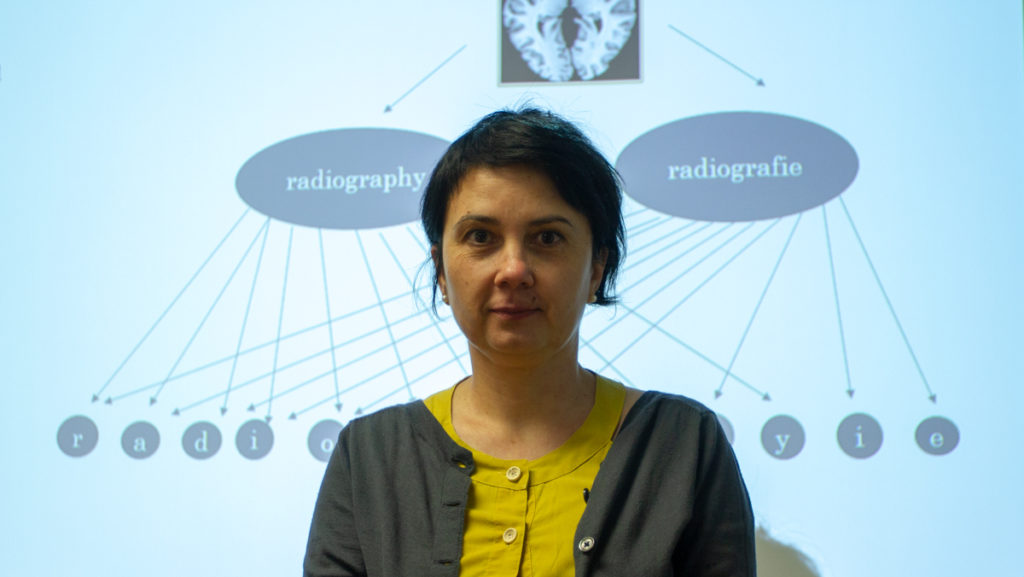

That’s why Muscalu conducted a study called “The illusory benefit of cognates: Lexical facilitation followed by sublexical interference in a word typing task” published by Cambridge University Press July 13. Contributing Writer Cody Taylor spoke to Muscalu about her study, the tests she performed and why these results are important in understanding how bilingual people process language.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Cody Taylor: What made you become interested in cognitive mechanisms involved in bilingual language processing, and how would you explain that?

Laura Muscalu: In psychology, as in many other disciplines, I believe it is a very good idea to choose a research topic that interests you very much at the personal level. Some time ago when I was a young international student doing graduate studies in psychology at The Claremont Colleges, speaking a ‘non-first-language’, I was struggling.

So, I really wanted to understand where the struggle was coming from. It was not clear to me what exactly creates this difficulty, and this is how I became interested in language acquisition. I wanted to know how people acquire a language … first language, second language, connoted L1 and L2 … how we generate words, why some words are more readily available than others, why we forget some words and not others, in general, how language is being comprehended and produced … I became interested in how bilingual people can juggle two languages.

CT: What would you say was the aim of your study? What were you trying to find out about word production?

LM: To explain the aim of the study, I think I have to backup a little bit and give you some context. The idea is that once you learn a second language your mind and your brain will never again operate the same as a monolingual person. Once you become bilingual, additional operations need to be employed. Moreover, it won’t be two separate, independent monolinguals that alternate just easily according to the needs of the speaker and its interlocutor. It is more than that. Because, from that time on, the two languages will always be simultaneously activated. So, for example, sometimes, when you are trying to speak or to write, it is easier to access a word when you know the other version of it. Because when you use a word in one language, you automatically exercise ‘the muscles’ of the translation correspondent through dual-activation.

But other times, the translations will compete with each other, and will preclude each other’s access. For this reason, mental processes like inhibition, selection, enhanced attention must be employed all the time, because you need to inhibit one language, select the one you want, you need to constantly monitor the activation of the two. In other words, you need to keep them in check.

This study is about these mechanisms of interference and selection, with specific reference to a category of words that are, surprisingly, aided by the bilingual status and vulnerable at the same time.

CT: Can you explain what a cognate is?

LM: Cognates are pairs of words, translation alternatives with the same meaning in both languages. They have similar but not identical forms. For example, you have elephant in English and you have elefante in Spanish. The idea is that cognates are very beneficial in the early stages of second language acquisition. When you are trying to learn elefante, it helps that you already know the word elephant. In early stages of L2 acquisition, it’s easier to memorize a cognate word than it is to memorize a non-cognate word because you already know a big portion of the cognate.

CT: Would you mind explaining sub-lexical and lexical levels?

LM: Traditionally the linguistics system has been divided by levels. When we produce language, we articulate words we may not be aware that there are so many levels, stages and process going on prior to that. There are three broad stages.

For example, if you are trying to say the word ‘dog’, you begin by thinking of this thing: something that has four legs, it’s furry, it’s black, brown, white, never green or blue; it has a tail, it barks, etc. At this stage, you don’t necessarily have the word, it’s only something abstract, some conceptual representation of the dog. That is the semantic level. This is how you begin word production.

Then, you go further and access the lexical level, and this is something that has to do with that label; it is some whole-word representation of what you are trying to say. Still not very, very specific, but it is some grammatical information, e.g., whether it is a verb or a noun, whether the noun has a gender, perhaps some information about how it sounds, in general, perhaps the number of syllables.

Then you go further and access the sub-lexical level (the level of phonology in speaking, or the level of orthography in writing). This is the level of sounds or letters.

CT: Can you explain what kind of experiments you conducted to come up with the results that helped you draw conclusions about bilingual language processing?

LM: In our experiments, we used several transition tasks in which people who speak two languages translated cognate and non–cognate English words presented on a computer screen and typed the translations. We recorded how long it took to translate and to type the translation. The two categories of words were compared.

Our results showed the time from the onset of the stimulus to the beginning of the response, which gives us some indication that people have translated the word and accessed the lexical representation, were shorter for cognates than for non-cognates. But the time to actually type the word was longer for cognates then for non-cognates. This suggested that cognates were accessed more easily during the first stages of production. That depended, of course, on how much match and mismatch there was in a cognate pair. The main idea is that even cognates can have a very hard time, and this was not expected.

CT: What are the implications of this research?

LM: The good part is that these mental operations that regulate dual language processing are being engaged and exercised a lot more in bilinguals than in monolinguals, and the training and the skills that they are gaining in the end helps them in solving all sorts of other problems — nonlinguistic tasks. It certainly pays off. And there is a lot of research that supports this idea. Overall, this kind of research contributes to our understanding of bilingualism, and it adds information to the models that are explaining how language works in general.