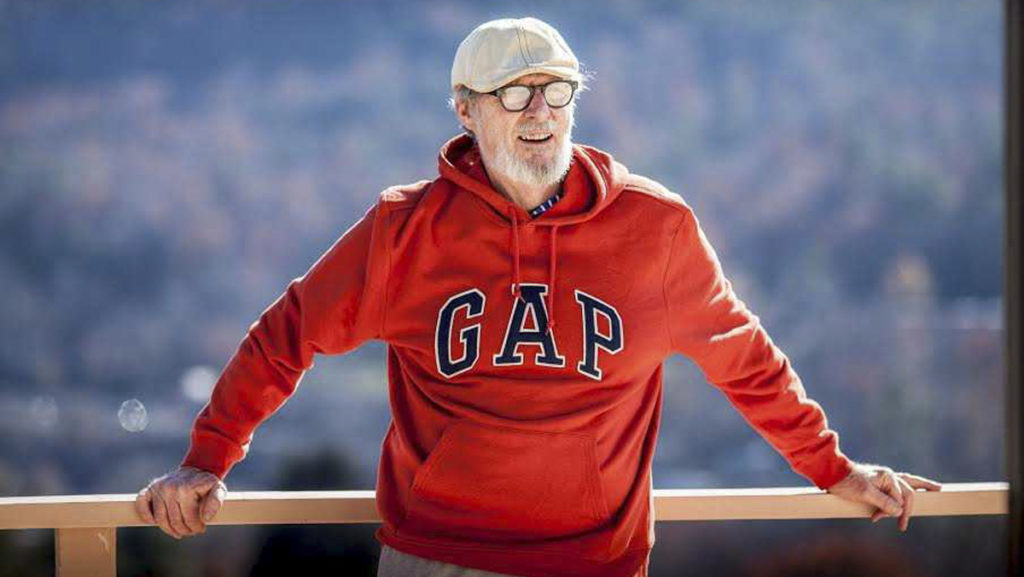

Paul Keane (IC ’68) is a retired Vermont English teacher. He served as program coordinator (1972–73) for the Kent State Center for Peaceful Change, the university’s official memorial to the students killed at Kent State. In 1977 he co-founded the Kent State Collection at Yale University’s Sterling Memorial Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Ithaca College’s public soul searching over the last two years since its president resigned after student activists criticized him for insensitivity to racial issues is a welcome act of institutional introspection.

When I graduated from Ithaca College in 1968 with a B.A. in English, the student protest era was about to explode over insensitivity to race and anti-war sentiment.

Little did I know that Collegetown on the opposite hill from Ithaca College would be paralyzed with student protest in April 1969 when Black United Students at Cornell University took over Willard Straight Hall, arming themselves with rifles to protest the burning of a cross on black housing at Cornell.

Cornell closed for a four-day teach-in on racism. I adapted that teach-in on racism to Ithaca College in 1969. Over 800 students and faculty attended.

Despite my activism at Ithaca, I decided to choose a quiet graduate school, and I enrolled at sleepy Kent State University in Ohio.

Within 8 months, four Kent State students were shot to death by Ohio National Guardsmen during a student protest.

The Kent State killings are about to pass into history. May 4 will be the 49th anniversary of that then-shocking 1970 event.

If you live long enough, you watch time do its “thing,” which is to drain all events of intense emotion and replace it with honorary emotion in inked phrases like the “Kent State tragedy” or the “Kent State event” or just “Kent State.”

Ink begins to dilute the blood.

But it cannot replace the blood of 20-year-old Jeffrey Miller, which I saw pouring from his head on the asphalt altar of a Kent State parking lot. He was dead instantly.

The phrase “post-traumatic stress disorder” did not exist in 1970, even though many families were receiving their wounded Vietnam soldiers back home suffering from its symptoms.

I suspect there were many of the thousand onlookers, even the National Guardsmen themselves, who experienced post-traumatic stress disorder after the shootings, unrecognized as such.

My own reaction was numbness, and then after waiting a year for an official justice which never came, outrage.

That outrage was translated into political lobbying for a federal grand jury and, later, into ensuring that a large portion of historical documents related to the Kent State killings went to Yale University’s archives, instead of Kent State University’s archives.

Why?

Because Ohio’s Kent State University Library was funded by the very entity which the parents of the dead students were suing: the state, which also funded the Ohio National Guard whose members had pulled the triggers.

Yes, Kent State will pass into history like the Boston Tea Party and John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry.

In a way, it is amazing that Kent State as a symbol of injustice and the passions of the anti-war movement has lasted now into the beginning of its 50th year.

On May 15, 1970, two weeks after Kent State, two black students were killed and 12 wounded by state and city police at Jackson State College, in Jackson, Mississippi, where a group of African Americans was demonstrating in response to the Kent State shootings and to a false rumor that the mayor of Fayette, Mississippi, — the brother of slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers — and his wife had been assassinated.

Jackson State has never achieved the traction of Kent State as a symbol of official violence of the 1970s student protest era.

Could that be because white flesh is valued in American society more than black flesh?

In a world where a movement named Black Lives Matter had to be created in 2013 after the shooting of black teenager Trayvon Martin, that sad reality may be the true lesson of Kent State.

Imagine if the Kent State dead had had black skin and dreadlocks. Kent State would have been forgotten in a few years.

While we like to believe all lives matter, the truth is that white lives matter most. That may be changing now as we inch next year toward the 50th anniversary of Kent State.

Ithaca College’s public willingness to examine its own institutional relationship to race may be one of the hopeful signs of that change.