Ithaca College sophomore Hunter Simmons sat at his computer Oct. 28 and prepared to fill out the junior off-campus housing application. When the form opened at 8 a.m., Simmons quickly submitted the request to live off campus and received a confirmation email.

A few days later, Simmons received an email from the Office of Residential Life saying he was one of hundreds of sophomores whose submission dates and times had been improperly recorded or not collected at all because of technical difficulties.

Technical difficulties with the application process resulted in students being randomly selected to live off campus instead of the typical first-come, first-served basis. As a result, sophomores — who had already experienced housing problems in Fall 2019 — have raised concerns about affording to live on campus next year.

Only a certain number of juniors are allotted to live off campus each year. The college advertises itself as a residential community, and its policy states that only seniors are allowed to live off campus without applying. Juniors must first have permission to live off campus.

Fifty-one percent of rising juniors were accepted to live off campus for the 2020–21 academic year, as stated in an email from the Office of Residential Life sent to all applicants. Even though there was a higher number of applicants, the college allowed fewer rising juniors to live off campus. According to Residential Life, approximately 238 juniors were accepted to live off campus, and 470 applied. There are 1,418 sophomores at the college, according to the 2019–20 Facts in Brief.

Marsha Dawson, director of Residential Life and the Office of Judicial Affairs, said the office does not have the number of applicants nor the number of people who were approved to live off campus for previous years immediately available. She said that the number of sophomores who are allowed to move off campus fluctuates from year to year and that this year allowed less students than the past few years.

David Weil, associate vice president of Information Technology, said 28% more sophomores applied this year than last year, and the system could not process the high volume of applications.

“I don’t know why there were more people this time trying to submit an application,” he said. “If we had reasons to believe that it would have been a higher volume, we certainly would have geared up for it.”

Dawson said the number of students who are allowed to live off campus varies yearly and depends on factors like enrollment and projections regarding the number of incoming freshmen.

“It’s not a determination that I make, it’s a determination that the institution makes with several offices and several different variables,” she said.

On Oct. 29, the application reopened and the application forms seemed to have submitted, but the dates and times people registered were not properly recorded by the system, according to an email from Residential Life. The email also stated that any forms submitted during the application window that met the eligibility criteria would be entered in a randomized lottery.

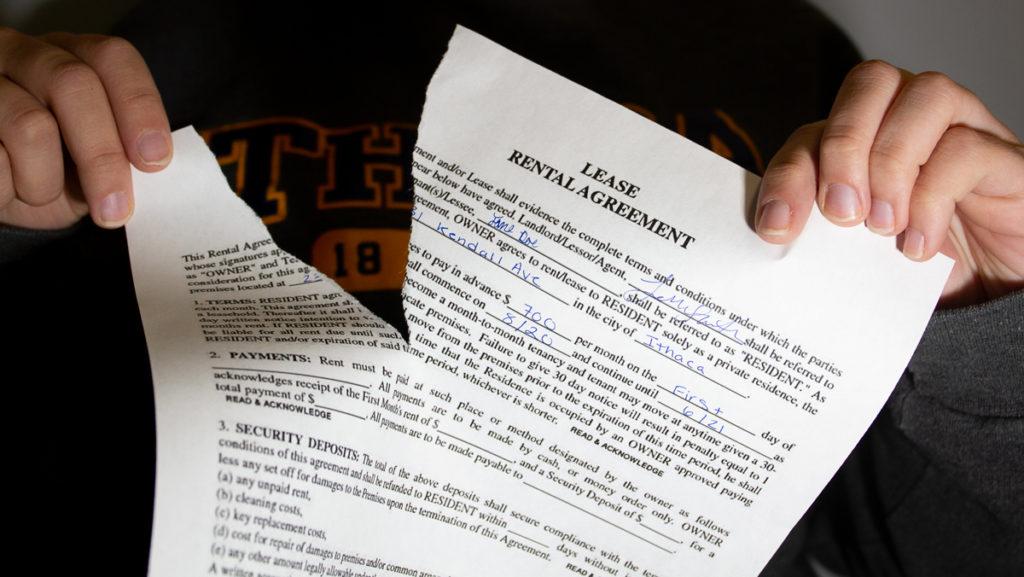

Many students have already signed housing leases for next year. If their applications to live off campus were rejected, the housing policy states that students will be required to pay for both on– and off–campus housing for next year if they choose to live off campus.

Students who were rejected now have to pay their leases and rents as well as the on-campus room and board costs. The Garden and Circle Apartments, the typical on-campus housing locations for upperclassmen, are the two most expensive housing options on campus, ranging from approximately $10,684 to $12,720. The college’s operating budget is primarily reliant on student–contributed revenue, including students paying for room and board.

Simmons, who pays for school largely by himself, said he is now considering taking a break from academics.

“Being unable to find affordable housing can quite literally cause some students to take a leave of absence,” he said. “That’s on the radar for me because I don’t know another option.”

This semester, there were issues with housing selection for sophomores as well. Many sophomores who would normally room in Emerson Hall or the Terrace Residence Halls found themselves placed in freshman dorms and the Circles — areas that are not typically allocated to sophomores.

Sophomore Isabel Johnston said she is wondering how the college plans to accommodate rising juniors next year.

“I feel like our class kind of drew the short end of the stick from the beginning just since housing from this year was a mess,” Johnston said. “They can’t accommodate the students that they have now.”

Dawson said that because the college guarantees housing, students often do not notify the college when they are coming back to live on campus, a situation that makes it so the demand for rooms is unclear.

Sophomore Joel Duval is one of many students who signed a lease at the beginning of the semester and said he feels trapped on both ends.

“If you want to rent something for a year in advance, the time frame is going to be in October,” Duval said. “The school has to know this.”

Dawson said that in the past, the application form has not opened until the spring semester, but it has been moved up in more recent years because students have begun signing leases a year in advance.

“We wouldn’t know that they’re asking students to sign leases sooner because students don’t tell us,” she said.

President Shirley M. Collado said the college encourages students to stay on campus to promote a better learning community.

“I would underscore that part of our philosophy in general is that we are primarily first and foremost an undergraduate residential college, and it’s our belief that we want to offer the best experiences that are affordable for students to be on campus at the greatest level,” Collado said. “Largely because of retention, student success, student engagement, student experiences, … we want students to live on campus most of the years they’re here.”

Collado said one of the main components of the college’s newly launched strategic plan is to address housing issues regarding both affordability and livability.

“We feel very urgent about the need to work on our master plan and really focus on student spaces,” Collado said. “In the meantime, I think our team has worked very hard not only to make the housing process earlier, … but also we want the process to be fair and open and transparent.”

Sophomore Theo Scott started a petition campaigning to allow all juniors to live off campus if they choose.

“I was fired up about it,” he said. “It seems a little ridiculous. Like why can’t we just live off campus?”

Rosanna Ferro, vice president of student affairs and campus life, said that if the college increased the percentage of juniors allowed off campus, there would still be students who are left out.

Ferro said students who feel they cannot live on campus for financial or medical reasons can individually appeal to the college. Dawson said there is no official appeal process at the time, but students can make appointments to speak with Residential Life.

Duval and other students met with Collado on Nov. 11 during her open office hours to voice their concerns, something Collado said she openly encouraged.

There were plans for a protest outside Holmes Hall following the meeting, but Duval said not enough students showed up to protest.

Dawson said an email will be issued to all applicants on Friday updating students on what has been happening and where things stand as a way to show students they are being heard.

“Meeting with students, one of the things I heard that there is a lack of transparency,” she said. “So when I spoke to some individuals that were facilitating the protest, I guaranteed that I would bring their ask forward and build with that and kind of provide an update.”