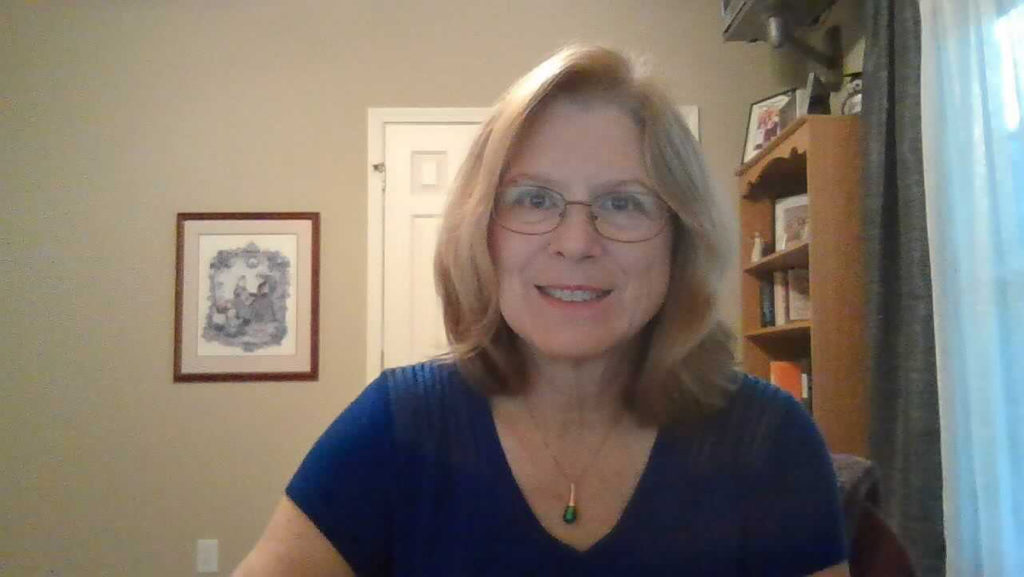

For the last year and a half, senior Clare Nowalk, a sociology major, has conducted research on the relationship between sociology and sex trafficking. Throughout her research, she has looked at the ways sex trafficking and abuse are portrayed in popular culture and the complicated relationship between promoting sexual safety while also respecting those who choose to do sex work.

In mid-November, she presented her findings New York Sociological Association general body meeting. She plans to continue her research next semester.

Opinion editor Brontë Cook spoke with Nowalk about her research, the difference between sex work and sex trafficking, and the ways in which both function in U.S. society today.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Brontë Cook: What inspired you to begin research on sex trafficking?

Clare Nowalk: So when I was young, maybe like fifth grade, it was the first time I got access to the teen section at the library. I remember walking in and looking at the books, and I found one called “Sold” by Patricia McCormick. … For some reason, it caught my eye. It turned out to be a book about sex trafficking in Nepal. I kind of have my mind blown. I mean, I was still in fifth grade, so a lot of it went over my head, but it was still this really jarring content. … After that, that was a subject that had always been interesting to me, so I had gone back to reading about it. And then at the end of sophomore year, … I was reading about a movie adaptation that was coming out of that book. I was doing some reading and then I was like, “Oh, I wonder if this happens in the United States.” Because you never hear anything about it online, and if you do, it’s very touch and go. … I knew this was a topic that I was really interested in, but there didn’t seem to be any combination of [sociology] and [sex trafficking] in … media or popular literature. It just feels like we’re having this sexual awakening in the United States, like you see people talking about sex positivity a lot online, yet we like refuse to talk about trafficking or abuse of any kind. So I wanted to see why that happens, what group dynamics occur that make people ignore this issue.

BC: How has your research evolved since you began?

CN: I traveled to the International Human Trafficking and Social Justice Conference in Toledo, Ohio, and listened to a lot of speakers there. I listened to one talk about sex trafficking and sex work. I went up to the speaker afterwards, who is a current sex worker and sex worker advocate, and I asked her about what I should do as a student researcher, and she said, “Don’t forget about sex workers.” I was too far into my research to change my subject at that point, … but then, this past year, [my professor] asked me to join her sex research tutorial, and I was like, “I want to continue doing this.” And as I begin doing that research, it’s really grown into this combination of “What is sex trafficking?” “What is sex work?” “Why do we tend to conflate the two in society?” … There needs to be an awareness of both of these issues, not just one or the other — like, how do we tackle the issue of trafficking and also respect the rights of sex workers?

BC: You’re focusing your research primarily on sex trafficking and work in the U.S. specifically. What role does it play in U.S. society?

CN: The average age of entry into “the life,” which is the term for being caught up in the sex industry, is around 12 [years old] in the United States. … It’s because of these other systems in the United States that are failing. Foster care is a big one. Homelessness, child abuse, … particularly when children, young women in particular, or LGBTQ kids, get put on the street and spend time alone or look vulnerable, they’ll tend to be recruited. … Sometimes for young women, particularly young women who’ve been abused or kicked out of home, that feels like someone who’s going to protect them. And then it really turns into this grooming. … It’s a gross term, but grooming someone for abuse.

BC: Why do you feel it’s important for people to have a basic understanding of how both sex trafficking and sex work function in society?

CN: I think a component of it is knowing what is happening to people in your own backyard. Like sex trafficking in Ithaca — trafficking does happen here. … We have investment in places we live, in the communities we come from, and when people are being hurt in our community then … what are we doing? I think another component is when you don’t know someone who’s been sex trafficked, and you think, “Oh, this doesn’t apply to me, like, I don’t need to do a lot about this.” Don’t we want everyone to be able to engage in sex in a positive way?

BC: So, what’s next in terms of your research?

CN: I’m continuing my research next semester. I’m going to be doing interviews with stakeholders, thinking about how sex trafficking is formed and how sex work is formed. Being in Ithaca, it’s hard to interview actual sex workers or sex trafficking victims. … So I’ll be interviewing activists, journalists, health care professionals, police officers … and comparing the way they all talk about this issue and the ways in which what they’re saying is similar.