From “The Civil War” to “Baseball” to “Jazz” — plus most recently, the excellent “Country Music” — filmmaker Ken Burns’ body of work has cemented itself among exhaustive and essential accounts of history. Now with “Hemingway,” co-directed by frequent collaborator Lynn Novick, Burns uses his series to disentangle fact from myth. In the process, Burns crafts the definitive account of Ernest Hemingway’s fantastical life and monolithic oeuvre.

The series spans a total of six hours broken into three episodes, each concentrating on a different phase of Hemingway’s life. Hemingway’s story begins with his years growing up in Illinois before serving as an ambulance driver on the Italian front in World War I. The author’s life will eventually take him to Africa, all over Europe and lead him to direct involvement in wars. Each moment of his expansive life feels appropriately weighty, befitting the subject material.

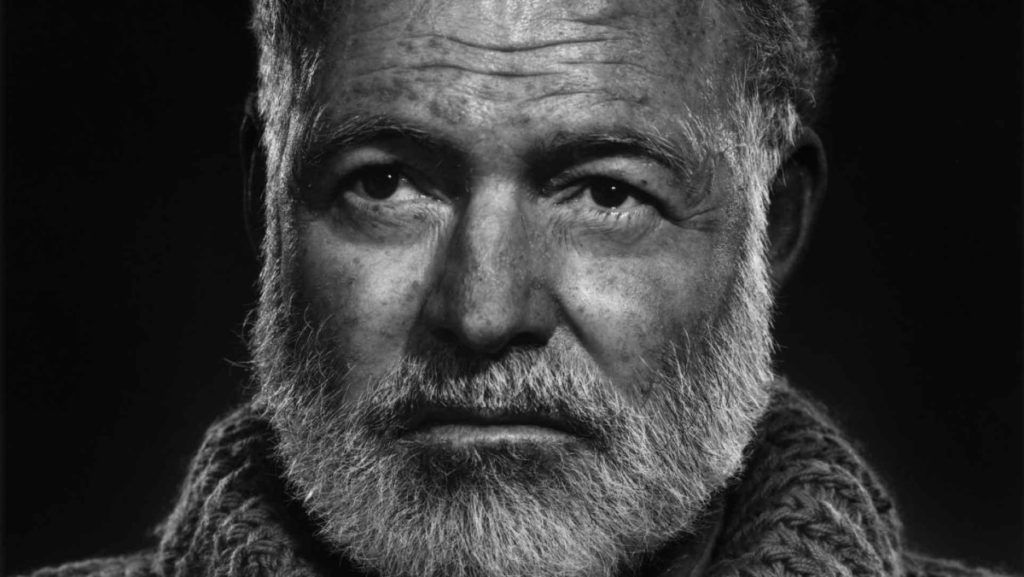

The story emerges over archival photographs, accompanied by narration from actor Peter Coyote. Dispersed throughout are talking heads of biographers and contemporary writers, like Michael Katakis and Edna O’Brien. Occasionally, voice-over by actor Jeff Daniels provides segments of Hemingway’s writing getting read aloud. Burns has perhaps the most easily recognizable style in documentary filmmaking. He treasures simple techniques like panning and zooming onto photographs to create movement within still images, a trick dubbed the “Ken Burns effect.” Evocative violin music underpins the narrative, always allowing the testimony to take center stage.

Almost all of Hemingway’s life appears at some point in his fictional work — like the protagonist of “A Farewell to Arms” being an ambulance driver during World War I. This means the analysis of the author’s writing plays a significant role in how audiences will eventually view the artist. Certain stories get confirmed, like Hemingway’s philandering attitude, which lasted his entire life, but what stands out more are the private accounts of Hemingway as a person. Growing up alongside his older sister Marcelline, Hemingway was often dressed in female clothes and called feminine nicknames. This instilled an androgynus nature to how he viewed gender that appears throughout his work, like “The Garden of Eden” or “The Sun Also Rises,” and in his relationship with his last wife, Mary Welsh.

“Hemingway” refuses to succumb to noncritical praise of the complicated man. Hemingway’s own memoir “A Moveable Feast” is full of self-flattery, but this series chooses to characterize his achievements with the context of his literary contemporaries. Telling the story of Hemingway’s early short stories and ventures into novel writing is also the story of modernist literature and the art world of Paris in the 1920s. Each character in the journey — especially each of his four wives — are given space for understanding where they stand in the larger picture of 20th century history. This includes the incredibly moving story of serious mental illnesses in his family, leading his father to take his own life and Hemingway fearing he would end up the same way. He did.

There are many sides to the story of Hemingway’s life and his place within the literature canon. Burns and Novick’s “Hemingway” touches on all of them until the author’s story becomes a difficult tragedy to reckon with. Burns avoids drifting away from hard facts, omitting the challenging questions concerning how to feel about Hemingway’s complicated legacy. The series never attempts to name Hemingway the author of the Great American Novel, though individual interviewees get quite close. For posterity’s sake though, “The Great American Novel” should be “For Whom the Bell Tolls.”