Capturing all the nuances of modern-day conflicts, in film or otherwise, is a difficult if not impossible feat. “Rosewater,” written and directed by Jon Stewart, overcomes this challenge by recreating modern-day Iran through the eyes of a journalist. The strength of its narrative is derived from the book “Then They Came For Me: A Family’s Story of Love, Captivity, and Survival” by Maziar Bahari, which chronicles the author’s 118-day imprisonment for “the crime of bearing witness” during Iran’s 2009 spiral from rigid authoritarian government to a totalitarian regime.

At the outset of the film, Bahari (Gael Garcia Bernal) is shown as a journalist living comfortably in the western world, cautious not to make too much of a stir with the content he generates. He is given an assignment covering the 2009 presidential election in his homeland of Iran and assures his pregnant wife that he will be back within the week. However, on the plane ride, Bahari blissfully flips through a magazine as the “Almighty Ruler of Iran” is praised by the overhead announcements, giving the viewer a preview of the propaganda that keeps the people of Iran under control — and that Bahari would rather not directly confront.

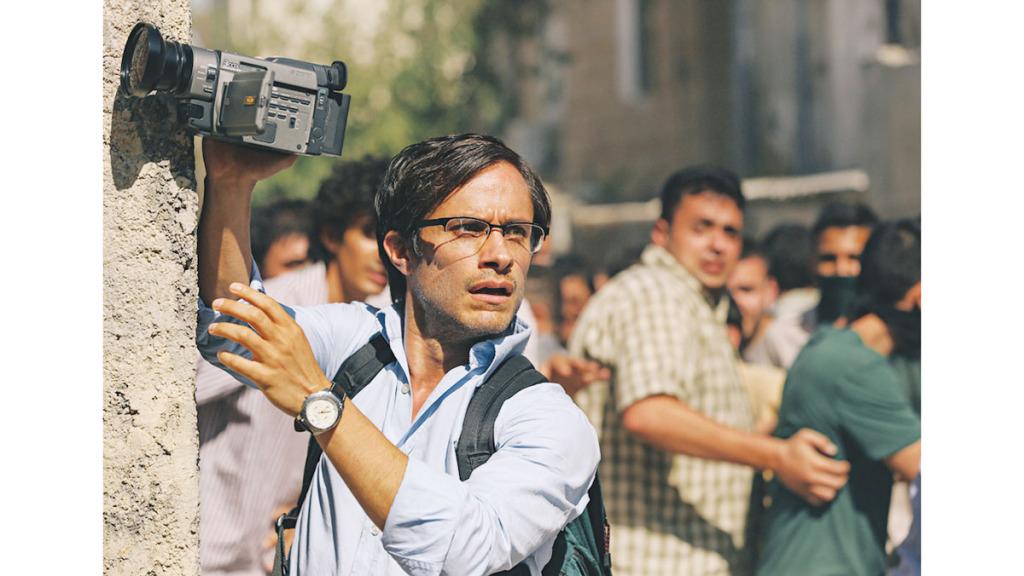

Though the incumbent ruler of Iran is re-elected unexpectedly, suspicions of fraud spark a wave of protests throughout the country. Many are peaceful, but one erupts into violence between the people and the government, leaving several of the protesters dead — and Bahari gets it all on tape. This is the offense that lands him in prison, where he is questioned and beaten.

The interrogators accuse him of being a spy, which Bahari denies repeatedly. Then, in one of the more intense and ironic moments of the film, they reveal the source of their suspicions: a satirical interview from a fictionalized “Daily Show” in which the mock-correspondent asks Bahari what it’s like to be a spy.

This scene also epitomizes the absurdity of logic that can be found throughout the film. The interrogators are far from the inhuman creatures they might have easily become. Instead, they’re simple human beings trying to advance in the only way of life they know. Bahari learns to take advantage of these human flaws, slowly unraveling the twisted ignorance that landed him in prison in the first place. No detail reveals the absurdity more than the time the interrogator asks, “Where’s Anton Chekhov?” referring to a deceased playwright Bahari liked on Facebook. Though it would have been easy enough to fall into the popular thread of evil terrorists versus the hero, the film takes a far more subtle approach, adding value to its story.

Even more amazingly, the film is able to accomplish this while assuring the viewer that Bahari is in constant danger. In his cell, Bahari is visited constantly by visions of his father and his older sister, both of whom were imprisoned and died mysteriously after defying the regime. Moreover, the rash actions of his captors fluctuate unpredictably from blind rage to smooth coercion, sometimes perpetrating physical violence against Bahari in addition to constant psychological torture. Again, the multilayered characters were the highlight of the viewing experience, and a little added suspense was also appreciated in an otherwise slow-moving film.

All praise aside, “Rosewater” relies principally on its subject matter to drive the plot: The directing choices do not often add significantly to the film’s appeal. The opening scenes — showing a short flash-forward of the day Bahari is arrested — detract from rather than add to the viewer’s understanding of the plot. Several of the most valuable moments of the film, like real footage of Iran shot out of the window of a car and flashes of humor as Bahari disarms his interrogators’ questions, were sped through too quickly for the audience to fully appreciate them.

However, several directing choices were as brilliant as others were poor: A mashup of social media commentary on the conflict in Iran highlighted a crucial element of the 2009 uprisings, and the final moments of the film were thoughtfully and perfectly chosen.

Overall, Stewart’s first crack at writing and directing on the big screen, even if it wasn’t perfect, highlighted a topic well worth watching. Even if some sloppy editing decisions at times added confusion, its subject matter was thoughtfully and interestingly portrayed.

“Rosewater” is a film that doesn’t rely on tried-and-true moviemaking tropes — both for better and for worse.