With the rise of social media and the fast-paced spread of information, librarians are now being asked to teach about the hidden messages in the media. Ithaca College’s Project Look Sharp, a non-profit dedicated to educating others on media literacy, plans to work with librarians to do just that.

Project Look Sharp received a two-year $270,000 grant in September 2021 from the Booth-Ferris Foundation — a program that provides grants to nonprofit organizations — which will be used to train two groups of 10 different K-12 librarians from across New York state on how to incorporate media literacy into the schools’ curriculum. For many librarians in the program, the workshop provides crucial insight into the hidden messages presented in media and how they are communicated to children.

The initiative, New York State Library Leaders for Media Literacy (ML3), is in partnership with the New York State School Library Systems Association.

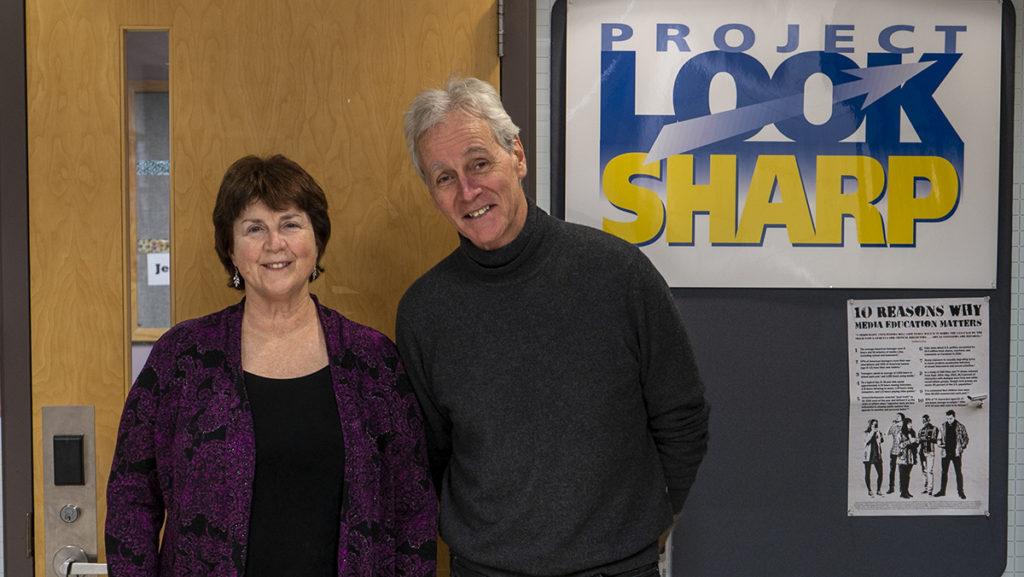

What started as a passion project between Cyndy Scheibe, professor in the Department of Psychology, and Christopher Sperry, director of curriculum and staff development for Project Look Sharp, in 1996 because of their interest in media literacy — the process of analyzing and creating media in different forms — evolved into an outreach program with over 550 free lessons for educators to enhance students’ critical thinking skills.

The lessons, Sperry said, were tailored to the preexisting curriculum that teachers had in subjects like social studies and science in order to adhere to curriculum requirements while also keeping media literacy relevant to the subject.

“We know that librarians are the information literacy specialists in the building … and they are in a unique position — particularly in K-12 school buildings — to be able to collaborate with the teachers at different grade levels in different subjects to support those teachers to integrate habits of questioning all media messages into the core curriculum,” Sperry said.

Michele Coolbeth, a librarian at East Syracuse Elementary School, is one of the participants in the program. For her, working with Project Look Sharp was the first time she attended an in-depth crash course on media literacy. In collaborating with other librarians, Coolbeth said she gained confidence in teaching media literacy to the students and teachers at her school.

“Whether we intended to or not, we have created a very media-oriented generation, and pretending otherwise is not helping us at all,” Coolbeth said.

One lesson Coolbeth was able to create for her school based on what she learned through Project Look Sharp was on Disney’s “Toy Story.” She said the goal of the lesson was to get students to think critically about the media messages in commercials advertising toys for the movie because commercials often portray the toy with special effects to engage the audience and encourage sales.

“They really enjoyed it because they immediately keyed into something that was recognizable,” Coolbeth said. “It just happened that it was in December. And so it kind of metamorphosed into how ads can be misleading for toys.”

Media literacy has become an important topic in recent years. According to a study conducted by Stanford University, 82% of middle-schoolers could not distinguish between an ad labeled “sponsored content” and a real news story on a website. The study of media literacy itself is not uniform across the United States — only 14 states have moved towards incorporating media literacy education in the K-12 curriculum, according to the U.S. Media Literacy Report 2020. In New York state, there is increased demand for media literacy requirements for K-12 schools. Civic and educational organizations are calling on the state to implement access to professional development for teachers around media literacy in order to meet media literacy education standards.

While media has evolved drastically in the 25 years since Project Look Sharp’s establishment — with media consumption increasing 20.2% from 2011 to 2021, and social media ad spending projected to reach $873 billion by 2024 — Scheibe said their approach to media literacy remains the same.

“The constructivist media decoding approach, teaching people to ask questions, probing for evidence … that hasn’t changed,” Scheibe said. “The media types have changed, but the basic approach hasn’t changed.”

Paula Trapani, a librarian at Lawrence Road Middle School in Long Island, New York, is another one of the participants in the program. While she began incorporating bits of media literacy into her work with the students and teachers in her school in the form of research projects prior to ML3, Trapani said she was interested in learning more about media literacy because of its prominence in recent years.

“The reality is every subject area is evaluating some form of media at some point,” Trapani said. “And it’s really critical that the kids know and the teachers know what they’re looking at and [if they] can trust it.”

In one activity, librarians were instructed to analyze the media messages of the Disney movie “Aladdin” from the perspective of a sixth-grader — scanning for potential problematic biases and stereotypes of the Middle East like colorism and orientalism — which Trapani said served as an initial exercise to get the librarians more confident in decoding the hidden messages behind movies, advertisements and tweets.

“The end goal is to make everybody just a little bit more aware of what they’re looking at, because pretty much everything we look at is considered media,” Trapani said. “And we don’t necessarily look at it without just learning all the time. Especially now … we have to be able to interpret it. You can’t just accept everything at face value.”