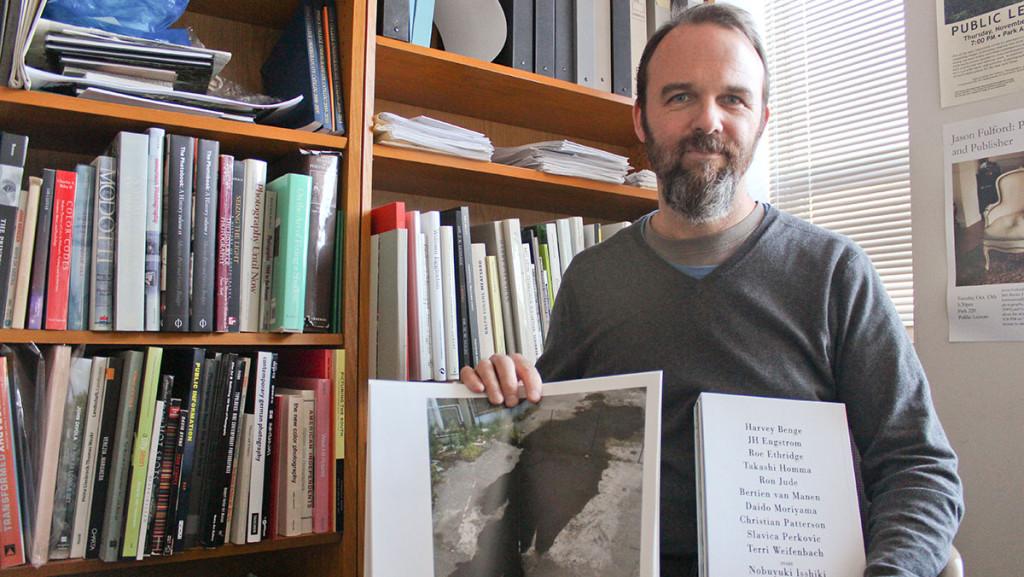

Ron Jude, media arts, sciences and studies professor, has taken photographs since he was a child. Growing up in Idaho, he would use his Instamatic camera to take pictures on skiing trips and later of his friends in high school. Little did he know, his photography would one day be exhibited in museums and galleries around the globe. Jude took a course during his undergraduate studies at Boise State University that allowed him to view photography in the context of art. From there, he pursued a career in the photography world.

Jude is the author of the photography books “Alpine Star,” “Ron Jude: Postcards,” “Other Nature” and “emmet” and is the co-founder of the publishing company A-Jump Books. Currently, his project “Lick Creek Line” is featured in the Robert Morat Galerie in Hamburg, Germany, until March.

Staff Writer Erica Dischino spoke with Jude about the “Lick Creek Line” project, what inspires his work and what his creative process is.

Erica Dischino: How did you end up in Ithaca?

Ron Jude: I was born in LA, and my parents moved us out to the desert to get away from the city. We then moved to Idaho, where I grew up and stayed until I was 23. Once I finished undergraduate school [at Boise State University], I was anxious to get out and see something else of the world. I went to graduate school in Louisiana, which couldn’t have been more of a culture shock having lived in Idaho for most of my life. I then moved to Atlanta for six years and taught at various schools. After living in New York City for a year doing freelance work, I got the job [as a professor] at Ithaca College in 1999.

ED: How did your childhood inspire your work?

RJ: It turns out that the last 20 years of my work have been somewhat autobiographical, even though it was never overtly designed that way. My projects over the past several years have to do with referring back to places that I’ve lived or sifting through the landscape and trying to figure how that place and landscape can affect who you are. I’m interested in memory and place and how that eventually affects who we become as people.

ED: How do you choose the subject of what your projects will be?

RJ: I do a lot of sniffing around, sort of like a dog. I try a lot of things and spend time in different places, sort of looking for project ideas. It’s a convoluted path that I’m following to get me from one point to the next.

ED: Explain more about the “Lick Creek Line.” What were your intentions?

RJ: The “Lick Creek Line’s” original format was a book. It’s also now an exhibition, but I arrived at how the work would be and how it would function by making a book out of the pictures. What the book is supposed to do is use the old documentary photo-essay model. I used that model very knowingly. I then turned it inside out to test that I never really fulfill, completely, the promise of the photo-essay. I use a fur trapper and the process of him checking the trapline as a way for the viewer to enter the landscape. I wanted [the viewer] to immerse themselves almost in a first-person sense. The idea was to bring you into the space that the fur trapper occupied in the mountains.

ED: Did you use the project to comment on fur trapping in any way?

RJ: It’s not a moral critique of fur trapping in a sense. I tried to use the fur trapper as a device. I liked that fur trapping is such a difficult subject, and because of that there’s a certain tendency in the work to romanticize the landscape. The act is so brutal and at times difficult to look at, so I liked the tension that the trapping created for the piece.

ED: You’re interested in the gray area between documentation and fiction. How do you represent that in your photos, specifically with the “Lick Creek Line”?

RJ: The documentary aspect is all surface. It’s how you enter the photograph. There’s a kind of realism to the way I take pictures. There’s nothing ever overtly mannered in how I take pictures, so there’s this sense that what you’re looking at is fact. The way I put things together is actually fabricated and serves whatever goal I have, so that’s the actual fictional aspect of it. There’s a certain seamlessness to putting the photos together, but in reality [the photos weren’t taken in chronological order]. There’s a sort of fictionalizing that goes into every photograph that’s taken.

ED: What advice would you give to those who wish to enter the photography world?

RJ: Always put the work first and be passionate about doing it. Forget about money, especially when you’re young. It’s easy to be poor when you’re young.