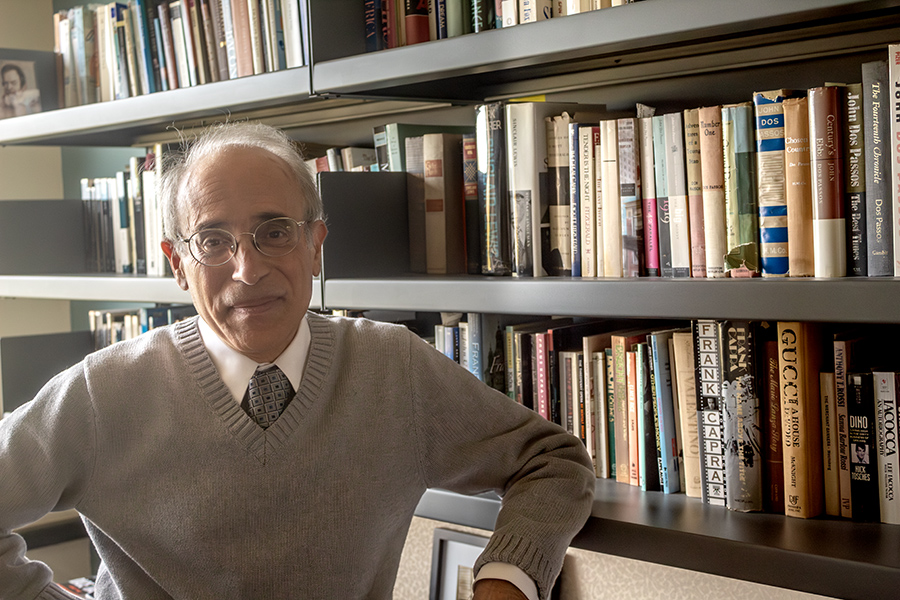

Anthony Di Renzo, a professor of writing at Ithaca College, recently published a book titled “Pasquinades: Essays from Rome’s Talking Statue,” on Oct. 28. The book started out as a collection of columns and essays that he wrote for “L’Italo Americano,” which is a bilingual Italian-American newspaper, and when approached about compiling the pieces into one work, he decided to take on the challenge.

Co-Life and Culture Editor Molly Fitzsimons spoke with DiRenzo about “Pasquinades,” the inspirations behind this complete work and the Roman culture surrounding this piece, as well as what the writing process for a point of view of a statue looks like.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Molly Fitzsimons: Why did you choose this topic?

Anthony Di Renzo: The editor-in-chief, Simone Schiavinato, had read my book, “Bitter Greens: Essays on Food, Politics, and Ethnicity from the Imperial Kitchen,” and he thought that I deserved a wider audience. I recalled that statue and the Pasquinade tradition and so I asked “What would you think about my being the statue and commenting on Rome?” Because Rome is always in the news, and the chat room is also a very polarizing place. The government seat is there, the church is there, movies are there, it is a city that traffics in illusions.

My head is full of Rome of the past, and Rome in the present, so I thought I could easily write a monthly column and say something interesting about Rome and always tie each monthly column to a holiday or some kind of anniversary or some national event that took place in that month and get things going.

And I did that for about seven years in the first year. Pasquino did talk to the reader to establish the kind of relationship I wanted him to have with the reader but after that, it was really just a kind of a column, he hardly ever addressed the reader directly. It was just really very much an op-ed piece. So it’s an editorial, a syndicated column or a blog in which reporting on current events. And that was the way that those columns were written for those seven years, all the way from August of 2013 to December of 2020.

MF: Were there any complications when turning the columns into a book?

AD: So Edward Hower, my editor, had read those columns, [and said] “Do you want to turn that into a book?” And he said to be just simply a matter of brushing them off a little and putting them together. And so I thought, “Okay, that would be a nice, interesting, separate project.” When we began to work together, it became clear that the columns worked as columns, they were not going to work as essays here for a number of reasons. First, in the original columns, you only have like 600 to 800 words. What can you do in 800 words? So you really kind of have a straight jacket, and so everything has to be very telegraphic, very stripped down and probably shorthand. And that shorthand also extends to the audience itself.

It’s a bilingual newspaper, so most of the readers are either extremely familiar with Italian and Italian culture or they are from Italy because although the print audience is 30,000, it’s more like 100,000 online. So I could assume that they would understand certain contexts and I could just mention the name and whatever. I wouldn’t have to explain anything, do any kind of details. But that’s not going to work for an American audience, an English–speaking audience. No matter how educated they are, they don’t add that almost instinctual understanding of the material. So everything had to be explained in a way that doesn’t kill the joke or doesn’t over–describe, but then you can’t put in too much information because then it’s like a guidebook — it doesn’t read easily.

So it took three or more years to transform those columns into essays. People are not just going to look at columns. They want a relationship with the speaker. So Pasquino then has to be a character. The narrator needs to have a personality. And more than that Pasquino has to have a backstory. The narrator has to have a motive. It’s almost a kind of a memoir of his life, but also a memoir of the city that Rome is, its kind of repository or a collective memory, and he can tap into it. So it’s a completely different way of writing. And that was hard. That was very, very difficult because I only agreed to the project because I thought it would be fairly easy to do. It really was a complete rewrite. And some of the pieces are almost completely new. But some of them are rewritten so much, they look nothing like the original columns reported.

MF: Could you elaborate more on your comment that Pasquino starts with talking to the reader and then shifts to more of a blog format?

AD: In the original columns, right, but in the book, he talks completely with the reader all the way through. It is a very intimate relationship, especially at the end when he has to say goodbye. And there the show shifts completely and he is completely different. So in many ways, it’s clear that Pasquino knows, he’s not immortal, that he’s saying goodbye. But if he had 1,000 years, 2,000 years, he could never tell everything that he knows and loves about his city to anyone. And so there’s this kind of vulnerability at the end about saying goodbye, we will not see each other. So it’s extremely, extremely intimate. And there are ways in which the columns are pure satire. They’re just like the politicians and you know, go for it, just go for the throat, but this is more than that. There are moments of real tender lyricism, beautiful poetic description.

MF: Did you find yourself writing Pasquino’s point of view first based on the knowledge you already had on the subjects or did you do research first and then add in his point of view?

AD: The feeling is in the material itself when you read these stories. It’s the same thing if you’ve ever read “The Decameron” by [Giovanni] Boccaccio, where this deceptively plain style of narrative where the emotions are all implied. They’re implied through action, they’re implied through gesture, implied through very spare use of dialogue. So as a narrator, Boccaccio will mostly summarize and kind of filter things through the perspective of his characters, but only when there’s something that only that person can say nobody else can say it, and that’s what I tried to do. The dialogue comes in like little pieces of Mosaic at a point where … it can’t be narrated and one has to be dramatized to record. The feelings are in the material itself. These are stories that I’ve known since childhood, but what I would try to do is try to find deeper facts. So the effect I wanted was something like one of my favorite auditoriums in Rome. So there is a small church called the Church of the Knights of Malta. But if you go to this church, in front of the door, there’s the gate that goes into the underside, so if you stood up here you look through the keyhole, you will see an opening out one of the most incredible vistas of Rome all the way to the dome of St. Peter just going down this avenue of trees that they have in the courtyard of the Knights of Maltas. And so if just looking at this little tiny thing, just the space opens up like this, to something very large. And that’s what that’s the effect that I wanted each one of those essays to have. It seems like a small thing, but when you look through, it’s very wide. So something small that provides a big perspective in a way that is easier. So it’s easy to read this like many of them, you can finish them in five minutes. And yet I want to be extremely memorable, five minutes that will stay with you at deeper resonance. So it was balancing between depth and compression on the kind of lightness and movement and was very, very challenging to get that right.

MF: Was there a specific reason behind choosing an independent press?

AD: I think that it’s just very hard to sell these to commercial presses. There are just a handful that maybe two or three presses in Canada and in the United States deal specifically with Italian American writers, which is the only place that I’ve really been able to be published.

So these presses now are more concerned about hearing these other hearing more emerging voices. And you know, I’m in my 60s now, I’m old, “Haven’t we done Rome already?” “Do we need another book about Rome?” So it was really, if Edward had not expressed interest in this project, I’m not sure anyone else would have published it at all. Because at least the initial impression, “Oh, it’s a common guide to Rome.” “We’ve seen these columns before.” “That’s nice, but we’ll pass,” but Edward helped me turn it into something else. But that’s really nowadays what most writers have to do. That’s where the action really is either self publish, or we go with small presses that will do something so you can see that a lot. The design, I had a hand in, the publicity I had a hand in. But the downside of that is that it falls on you to market the book to push the book in that way. But that’s the way that the publishing has gone. And you have to redefine what a successful run is. So back in the old days, like a midlist book, it maybe got 1,000–3,000 copies and that’s good. If you get good reviews then you did well, right, you’re not the best seller, whatever, but all right. When you’re in a small press like this, then you’re really looking at a successful run is more like 300–500.

MF: On the faculty page that you have, it says that you were hired as a secretary for Pasquino. I’m just wondering why you made the decision to include yourself, as an extension of the storytelling rather than just having Pasquino narrate?

AD: Because that was the joke, that Schiavinato set up in the original column, that they use me as a secretary and the way that Pasquino says I’m using him as my secretary, but also because change professional and technical writing here at Ithaca College, and for many, many years I was the recording secretary of my department, so this is kind of an in joke about being the secretary because I function in that way in my real life, in many circumstances, and so that is why it’s amusing to identify me as Pasquino’s secretary.

Marshall Getz PhD • Nov 14, 2023 at 9:36 am

Looking forward to reading this. Thank you