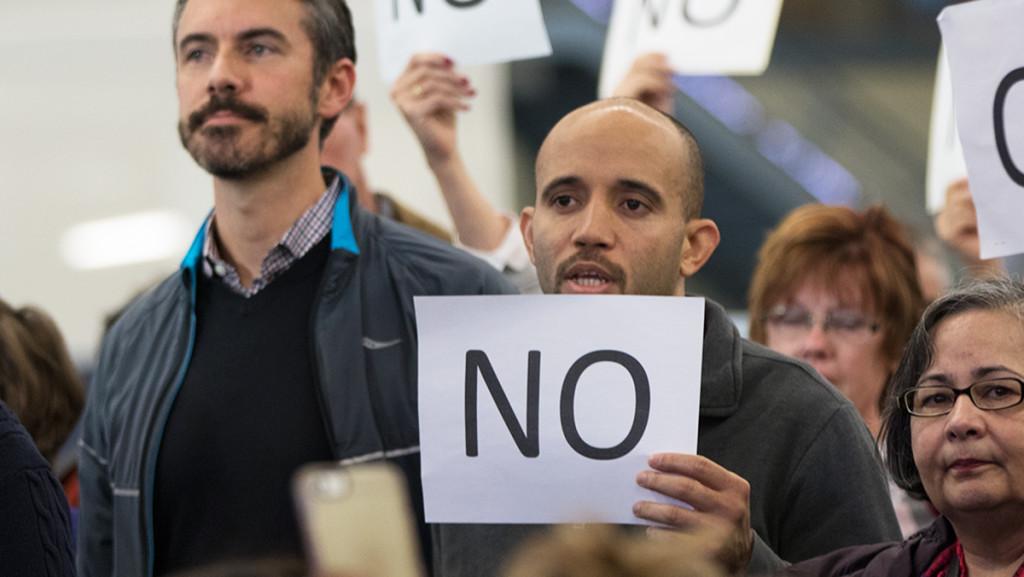

“No more dialogue, we want action.” I first heard this chant at the tail end of a student demonstration at Free Speech Rock in late October. I have since heard it repeated on the Academic Quad, in the Fitness Center, walking through Job Hall, in the rooms where I teach, even in this very newspaper. Yet, for as often as I have heard it mentioned, very rarely do I hear it used in quite the same way. There appear to be various interpretations of its meaning that have resulted in intense disagreement on our campus.

While it is important to think through the differing interpretations of the chant, I find myself more interested in what lies behind it, particularly its first clause — “no more dialogue.” I am referring to the historical context that informs the current dialogue on race and injustice preceding its use here at Ithaca College this semester. I have taught at the college level now for just shy of 10 years (including six as a graduate student) and confess that my teaching has always been informed by this historical context. As a person of color born into a monochromatically white family, I have lived through almost four decades of debate about my body, my intellect, my opportunities and my selfhood, all of which are shaped by this historical context. My research interests have shown me that the historical context for this dialogue far predates my own existence — the Civil Rights Acts and movements of the 1960s, the Plessy v. Ferguson decision and the Emancipation Proclamation are all significant products of an ongoing dialogue on race and injustice over the last 160 years, and which stretches even further back to the initial colonization of the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Race and injustice, particularly in the way they were employed to create cheap/slave labor to concentrate economic wealth in the hands of the few, are intricately linked to industrialization, globalization, capitalism and other institutions that serve as foundations for structuring the world we all exist in. Dialogue about race and injustice has followed these forces across the globe and over centuries, seeping into nearly every facet of our lives.

Despite our best collective attempts to protect ourselves behind a shield of post-racial rhetoric, race and injustice continue to matter. By design, certain individuals and groups feel the presence of these forces much more keenly than others, which may begin to explain the differing interpretations of the dialogue on them. Our own unique relationship to race and injustice greatly influences the degree to which we can, and sometimes must, participate in the dialogue. I have not been able to escape it at any point in my life; this moment is not my starting point. And, quite frankly, it’s exhausting, a kind of overwhelming racial fatigue. I would be shocked to discover I am alone in feeling this way on our campus. At times, I want the dialogue to cease so that I may catch my breath and focus on the many other wonderful aspects of my life. I hope it ends because our world no longer needs it in order to function. Yet, racism and injustice persist and so, too, does the dialogue.

Rather than offer my own extensive interpretation, perhaps it is helpful to outline a brief (non-exhaustive) handful of questions I explore when hearing the current debate on “no more dialogue”:

- What individuals and/or groups control what is discussed as part of the dialogue?

- Whose voices are heard most clearly?

- Who has power to determine access to discussion forums?

- Whose languages are privileged in discussion forums?

- How socially, politically, racially and economically representative are the voices?

- Does the dialogue operate under a set of collectively agreed upon truths (i.e. acknowledgement that racism still exists)?

- How informed are participants on the subjects being discussed?

- Who speaks from lived experience? Who doesn’t? How does this shape what they say?

- What does the speaker have at stake?

Speaking only on my own behalf, when I hear “no more dialogue” I do not understand it as a call to disengage from others or an attempt to silence particular voices. It is not illustrative of shying away from potential social progress or aggravating racial tension. Instead, it is a refusal to accept the terms on which the dialogue has been facilitated over time, which involved an underrepresentation of minoritized voices, invalidation of the personal experiences of the oppressed, the dismissal of evidence of oppression of all forms, victim blaming, personal shaming and often visiting violence on the bodies of the marginalized. Even in more tepid sociopolitical periods, the insistence on dialogue over action has functioned as a passive-aggressive method for ensuring underwhelming, limited social progress. Sometimes less.

What we must aim for now is dialogue on race and injustice that challenges entrenched mechanisms of power without reemploying them. It must account for historical context without recreating it. Nor can we repeatedly begin from square one, so getting educated and becoming better informed is your individual responsibility. Insisting on dialogue while failing to consider your own starting point is counterproductive. Insisting on dialogue without considering dynamics of power is irresponsible. Most of all, dialogue without action as its principal goal is regressive

and disempowering.

Derek Adams is an assistant professor in the Department of English. Email him at [email protected].