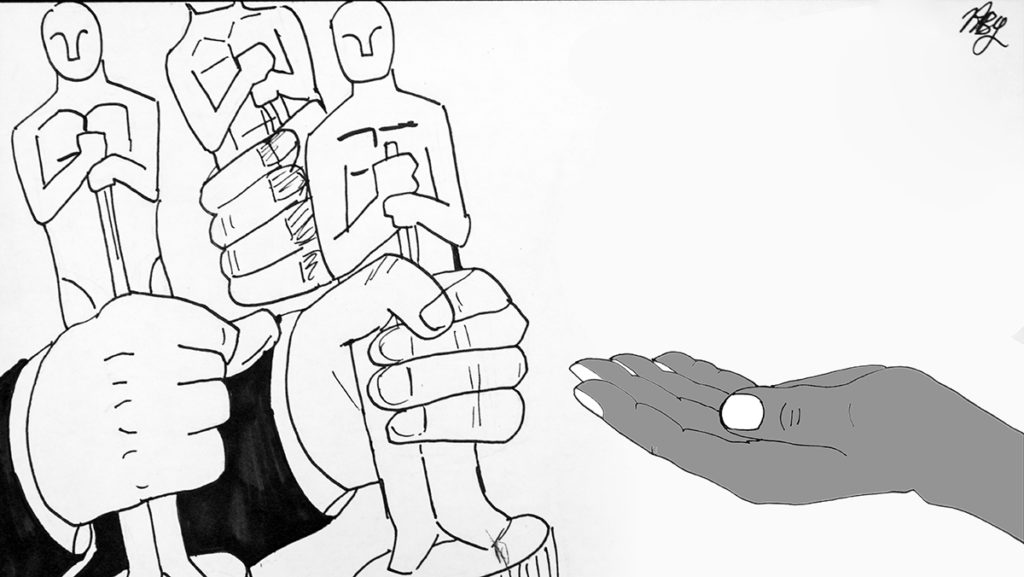

It’s no secret: The Oscars have a race problem.

For what is considered the most prestigious of cinematic award shows, the Oscars have a history composed primarily of white nominees and white winners, with a scarce number of nominees of color and an even scarcer pool of Oscar-winners of color. It’s a historical and systemic problem — in the Oscars’ 89-year history, having a nearly all-white group of nominees has been the norm, not the exception.

This year’s batch of nominees, however, constitutes the most diverse group the Academy has seen in recent years. Each of the Oscars’ acting categories recognizes an actor of color, and six black actors have been nominated, which is a record for the award show. Out of the nine films nominated for best picture, four of them center around people of color.

With this racially diverse selection of films, actors and filmmakers, many have begun to think maybe the Oscars aren’t so white after all. But the number of people of color nominated for an Oscar should not be the only marker for cultural progress — the quality and content of these films matter just as much. Diverse representation is not just important for the marginalized groups who see themselves reflected in art but for those on the outside who have the opportunity to be exposed to experiences and stories outside of their own periphery.

The racially diverse films recognized by the Academy also reveal a problem with how mainstream America consumes films about race. The last two films focusing on people of color that won prestigious Oscars in the best picture or acting categories were “12 Years a Slave” in 2014 and “The Help” in 2012. The single theme connecting these two films: the story of slavery or servitude to white people.

It seems that Hollywood prefers predominantly black films that focus on racial struggle, highlight the black characters’ relationship with white people and are set in the past. This trend sets a dangerous precedent for how people evaluate the current state of race relations.

Making films set in periods of intense racial divide and struggle cements oppression as a relic of the past, an evil that has been dealt with, and, more insidiously, an evil that has been conquered. This trend perpetuates the idea that this society has transcended racism, an idea that could not be farther from the truth. Instead of contributing to racial progress, these films soothe sensibilities of white people into believing they no longer have to worry about racism — delaying progress even more.

In future years, the Academy must continue to look outside its white, cisgender, heteronormative lens. More importantly, the film industry and its consumers as a whole must step outside their constant romanticization of racial struggle as what constitutes art. While this year’s Oscars are certainly a small step forward for recognizing people of color in film, this does not mean the fight for greater visibility has ended. It has only begun.