Professors of color occupy a distinctive position at a predominantly white institution. It is often the case that they must take on responsibilities that reach beyond the institution’s expectations for them as professors.

This is the reality for many professors of color at Ithaca College. Not only are these professors expected to fulfill the responsibilities of a good teacher, but they are also expected to be the face of diversity at an institution that is predominantly made up of white people. These heightened expectations end up placing cultural taxation on professors of color by burdening them with more responsibilities without much support.

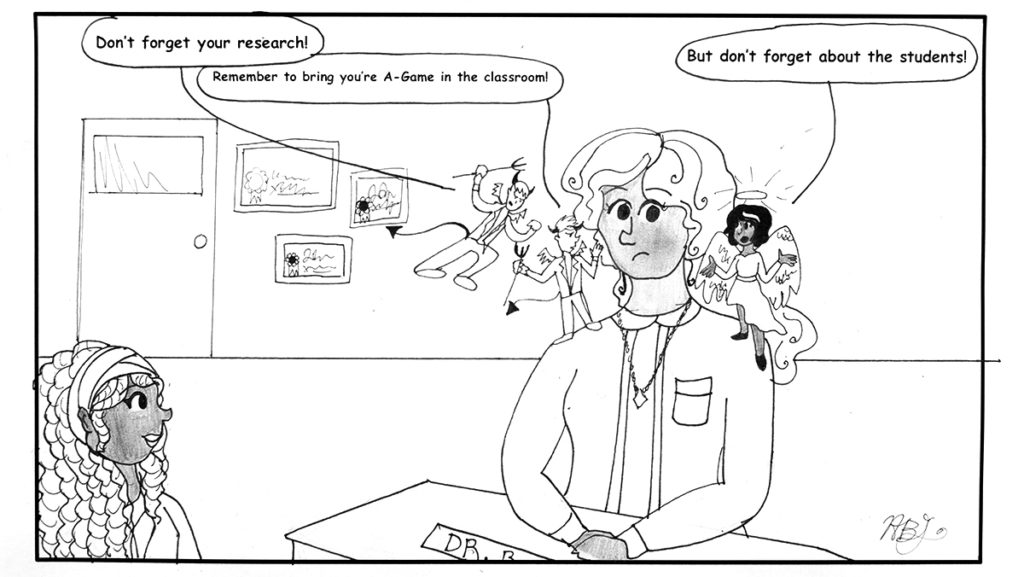

It is also the reality that professors of color end up mentoring students of color more, as students of color often feel more comfortable talking to professors who may share the same identities as them. Yet by taking on this role, professors of color find less time to dedicate to other areas of study. Trying to meet the multitude of demands of a professor stretches their mental, emotional and physical capacities into areas of work where their contributions may not even be accounted for. Measuring the performance of professors of color with the same standards used to evaluate other professors who may not put as much time into mentoring inherently disadvantages professors of color, since service is at the bottom of the list of priorities in the tenure evaluation process. It’s a system that pushes professors of color into a game that is high risk with low reward.

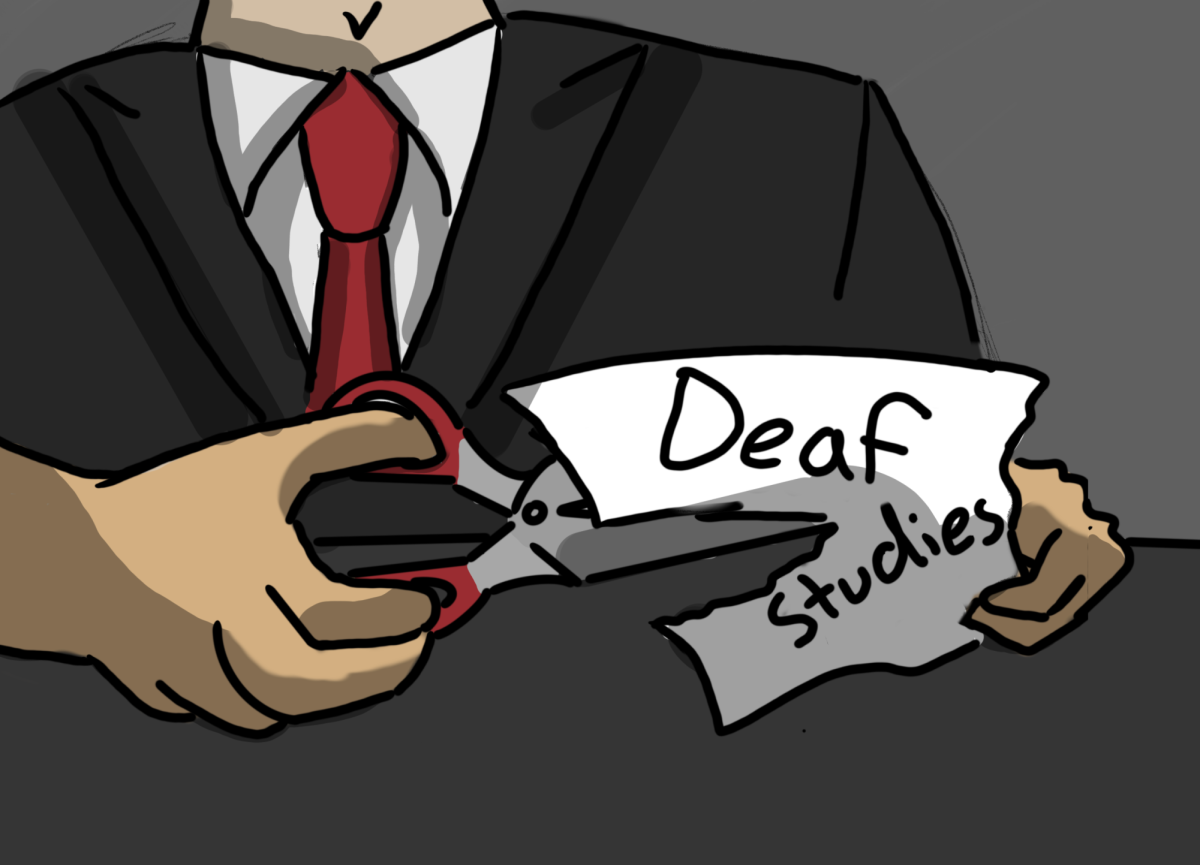

The tenure system at this college is constructed in a way that disadvantages professors who dedicate time to helping students. Out of the three factors reviewed in the tenure process — teaching excellence, research and service — service is at the bottom of the list. For professors of color, this puts the possibility of tenure farther out of reach by not taking into account the distinctive experiences and expectations of professors of color to service the institution’s diversity needs. If the tenure system is to provide a fair shot to ethnic minority faculty, the review process must be restructured to acknowledge their extra inherent responsibilities.

Of course, there are other professors at the college who also invest time to mentoring students. However, the difference lies in the reality that there are fewer resources available for students of color outside of talking to professors. The lack of adequate counseling services for students of color makes this dependence on professors of color even greater.

It is admirable that professors of color dedicate the time and energy to mentoring students of color — it is a contribution to the community that deserves recognition. For the college to not reward or recognize the work done by professors of color is unfair and even devaluing. If the college is truly dedicated to creating an inclusive space, then it can begin by providing more resources for professors of color and students of color to alleviate many of the extra responsibilities these professors must carry. Simply viewing them through a lens of diversity without truly acknowledging the distinctive struggles they face exposes the administration’s commitment to diversity and inclusion as solely performative, not substantive.