On April 16, the workers of Cornell University’s College Ave. Starbucks went on strike, only a week and a day after having voted 19–1 to form the 15th American Starbucks union.

That morning — while the coffee shop was already overworked and understaffed — the grease trap in the kitchen overflowed, spreading a cocktail of congealed kitchen grease, oil and runoff across the floor. Despite customer complaints of the odor and workers trying to close the store for safety, the store was kept open. This decision was made by the store’s then-acting manager, Victor Rodostny, who did not respond to a request for comment.

“I told him that it wasn’t safe to stay open and [that] I’m closing the store,” Benjamin South, the store’s shift supervisor said. “He immediately came to the store and demanded we open it back up. [The workers] talked about it … I said ‘Hey if we were to walk–out on strike would y’all want to do it?’ and we all agreed that we would.”

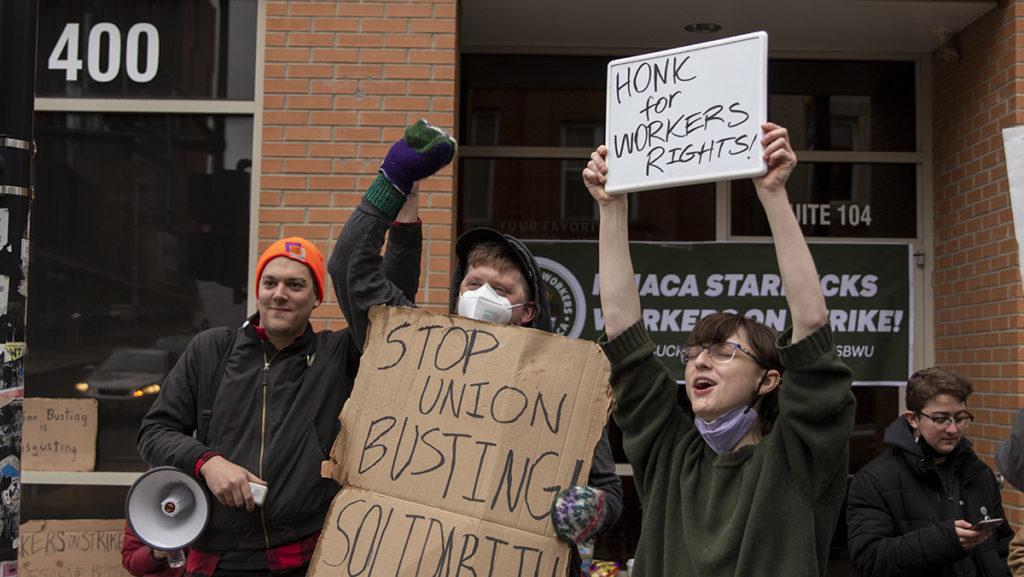

The strike began around 11 a.m. and continued until the evening. Workers held signs outside the store reading “Honk if you support partners” and “Union busting is disgusting.” The store was closed Saturday due to the strike and remained closed on Sunday while the grease trap was fixed.

“They [management] said that they were going to fix the [grease] trap on Monday, so we were like ‘let’s strike until Monday,’” Evan Sunshine, a barista at College Ave. said. “But then they were like ‘Oh my God, they’re actually going on strike, this is a big deal.’ So they actually sent the guy to fix it on Saturday. It really goes to show that striking does solve the problem.”

The strike was eight days after College Ave. and Ithaca’s two other Starbucks locations — South Meadow Street and The Commons — won wipeout union elections. The elections were one of many union elections that overcame Starbucks’ nationwide union-busting campaign, which has been described by many as illegal.

Amanda Laflen, College Ave.’s permanent manager stepped into the role in February 2022 after the workers filed a petition to unionize. Laflen has allegedly bullied her workers and created a stressful work environment, according to the workers. Laflen declined to comment.

“[Laflen] went on vacation a few days after we won our union,” Nadia Vitek, a College Ave. worker said. “It’s pretty funny timing because she got sent here from California to union-bust us.”

Vitek said Rodostny — the manager of the Meadow Street Starbucks who filled in for Laflen while she was on vacation — would not listen to pleas from the workers that they were overworked and understaffed.

“The manager standing in for us [during the grease trap spill] … all he did was turn off mobile orders,” Vitek said. “We’re just constantly not being listened to by managers. They assume that we’re overreacting because we’re expected to work while suffering.”

[slideshow_deploy id=’43754′]

South has worked at the College Avenue Starbucks since 2018. South said the grease trap at that location has consistently failed for years, and has never been meaningfully fixed.

“It was impossible to clean up with just a mop and some rags and the smell was putrid,” South said. “It’s something we’ve been begging them to fix for years. It’s just so unsanitary. I didn’t feel comfortable. Since the first day I came here, they joked with me about it [the grease trap] in 2018. They seal it up, but they never fix it.”

The Department of Labor’s regulatory agency, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) lists multiple hazards grease traps can cause. Over time, poorly kept grease traps have the potential to create toxic and flammable gasses like methane, hydrogen sulfide and carbon monoxide. OSHA requires employers to use personal protective equipment to clean grease traps.

Sunshine said Starbucks does not supply workers with any personal protective equipment to clean the spills from grease traps.

“We are expected to clean that ourselves — without any protective equipment,” Sunshine said. “We have a mop and rags, but that’s pretty much it.”

A spokesperson for Starbucks’ media relations department said she was not aware of any potential safety protocol violations that occurred.

“We take our safety protocols very seriously and our safety protocols and policies are in place to protect partners and protect our customers and the communities we serve,” the spokesperson said.

Vitek said that when the store filed for a union in January, the store took a “nice guy approach” to the workers by addressing issues workers had raised as to prevent union efforts from taking off. One of the workers’ requests was for the grease trap to finally be fixed, which Vitek said management listened to and brought someone in to make repairs. However, the fix to the grease trap was only temporary.

“For a month [the grease trap] has smelled horrible all the time,” Vitek said. “In fact, on top of the grease trap there’s just hundreds of dead maggots there. It’s disgusting.”

The workers were able to be compensated for the hours that they lost while striking due to a GoFundMe that was started at the beginning of the strike to help cover their wages. As of April 20, the GoFundMe has raised $2,672.

Scout Coker is a College Ave. worker who was scheduled to begin a shift at 1:30 p.m., but decided to attend the strike at 11:30 a.m. when they heard about it after waking up. Coker said the union allowed them to not worry about getting fired for the strike and credited the strike for getting management to listen. Coker said that by Monday, the grease trap had been cleaned enough to resume work. However, the long term solution — which is to remove or replace the grease trap entirely — has not yet happened, as the pipes connect to D.P. Dough, a restaurant next door.

“As unfortunate as it is, the management is not paid to care about you,” Coker said. “Unless the issue is immediately dangerous for your safety — or sometimes when it is dangerous to your safety — they’re not going to fix it … Standing up [and striking] has gotten us infinitely more support than I’ve gotten from any manager in my five years at this company.”