Ithaca College’s Fall 2023 course catalogs reflected curriculum changes that have been in the works for the past few years, as many schools at the college have shifted from three- to four-credit courses.

Following recommendations in the 2021 Shape of the College plan, departments submitted curricular revisions between September 2022 and March 2023. These changes included decreasing the required quantity of credits in a major, adding options to meet major requirements and restructuring material into new courses with a different number of credits. The last of these changes were implemented in the Fall 2023 course catalog.

In a four-credit model, students could take four classes instead of five. The college said this would make class material denser and allow for students to fully invest themselves in learning about a particular subject. Professors would be expected to alter their previous three–credit courses to four-credits courses by adding more information to the courses and extending the hours that their classes meet. This means a potentially heavier course load for a single class and lengthier meeting times.

Faculty Considerations

Jason Freitag, professor in the Department of History, said the college highly encouraged the shift to four credits as departments revised their curriculum but did not enforce it. He said some faculty in the department were hesitant to alter their previously well-established courses.

“Each one of our classes needed to be resubmitted for approval,“ Freitag said. “There were some people that were eager and believed it would be good for faculty, good for students and allow faculty to focus more, while others believed three credits was the more optimal way.”

While discussion has been ongoing, some departments officially told professors that their courses were going to increase to four credits in May. This meant that professors had until the start of the Fall 2023 semester to adjust their courses — an amount of time that derived mixed reactions from professors.

Marella Feltrin-Morris, professor and chair in the Department of World Languages, Literature, and Cultures, said she observed that some professors found the four months too short to effectively overhaul a curriculum and add enough content to be worthy of four credits.

Freitag said faculty workload was also a major consideration in altering credit hours. Professors were instructed to alter their course to contain more information to support a four-credit workload. While given guidelines and offered to expand, some professors chose to add more information at the end of the curriculum.

Feltrin-Morris said that adding more information at the end of her courses was a simple, seemingly effective option.

“I’ve always felt that within 50 minutes it was always hard to accomplish everything I’ve wanted to accomplish when teaching a language class,” Feltrin-Morris said. “Because it’s longer, I’m allowed to switch activities more.”

William Kolberg, professor in the Department of Economics, said that while adding information to the end of courses works with linear classes, classes with broader subjects often went in completely different directions. Some scaled back and focused on minute details in the scope of a course.

Despite classes getting longer, professors have found that combining course topics together allows for more in-depth information to be discussed but can consequently lead to the combined information exceeding the amount of time allotted. Kolberg said he has begun to see some minor issues in combining the two larger, separate courses of Principles of Microeconomics and Principles of Macroeconomics into one course: Principles of Economics.

“I’ve taught it the other way for so long, it’s refreshing to get a chance to do it the other way,” Kolberg said. “Having said that, it’s a lot of work, and it’s an issue to compress these two larger classes into one.”

Results

Kolberg said certain professors have found that their students are having a difficult time adapting to the high volume of information over sometimes shorter class periods. Kolberg has found that different professors have completely altered their teaching strategies mid-semester, while some have stayed mostly the same.

“We changed content, but teaching strategy is an interesting issue,” Kolberg said. “In my principles [classes,] I haven’t changed the strategy at all. … In my other class, I’ve done a lot more activities and I think that’s helped a lot and varied.”

While times in general have been extended, the way these times are portioned varies between professor and class. Professors can have multi-hour long blocks, while others may split into shorter blocks across many days. Freitag said this new method can create an immense amount of expected attendance from students who may already be busy with other classes.

“That, I think, is the space we just don’t have enough information of how that’s going to work out,” Freitag said. “What is the actual class meeting schedule that is pedagogically best and what the students are most interested in. … 100–minute classes are hard. It’s a lot of time to fill.”

Junior Ally Aretz, a biochemistry major, said she feels that taking fewer classes is optimal even though finding classes that fit together may be harder.

“It makes classes a little hard scheduling–wise to fit in. Three days out of the week are fine and then the fourth affects my schedule,” Aretz said. “Other than that, more credits [per course] is nice since I have to take less classes and then it’s a little easier to manage.”

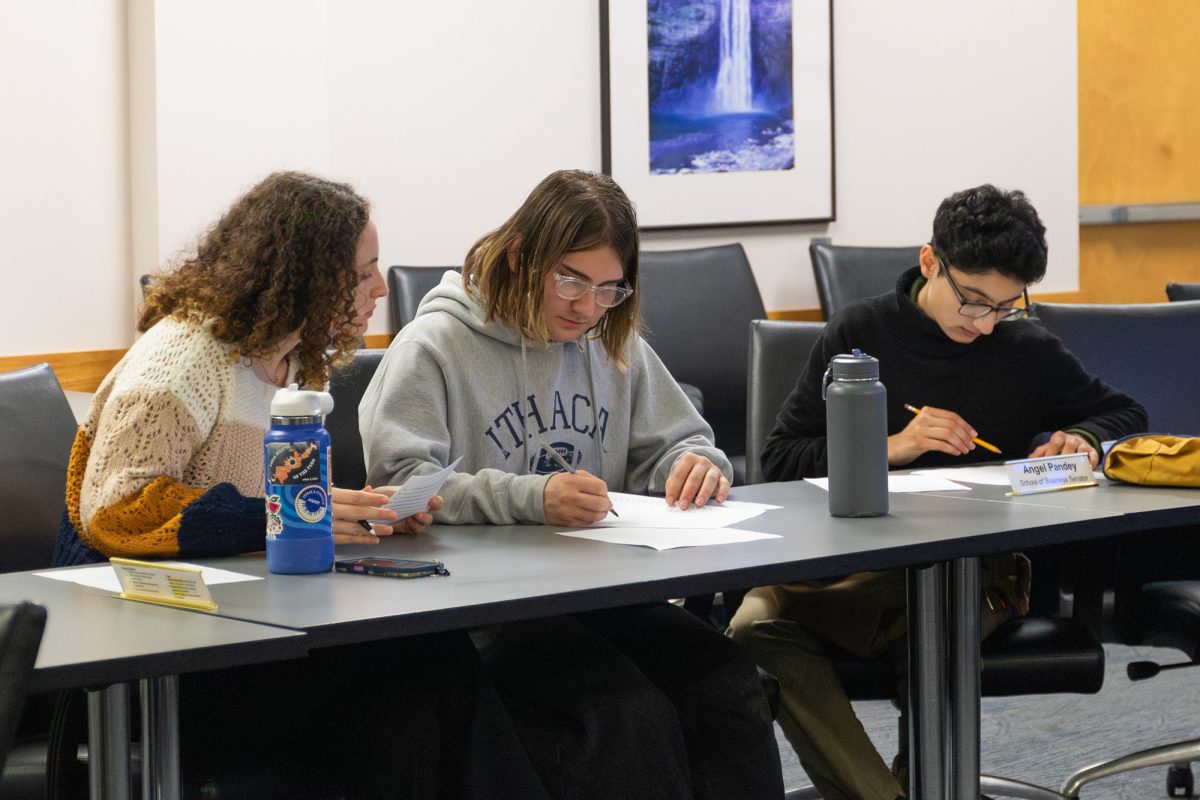

Sophomore Hank Jennings, a cinema and photography major, is minoring in history. He said the credit change has made the classes he has taken significantly rise in difficulty compared to his classes in the Roy H. Park School of Communications.

“It definitely feels like a bigger time commitment, not just in class times but also readings,” Jennings said. “I have two history classes and two Park classes and my two history classes have been way more work.”

Departments focused heavily on the results of midterms compared from Spring 2023 to Fall 2023. Freitag said that while the Department of History was slightly worried about midterm grades declining, it has not seen major changes.

“I haven’t heard any informal chatter of issues with grading,” Freitag said. “We don’t generally look at grade distribution like that. … I think I’m seeing what I normally see, but I’m seeing them for longer.”

Feltrin-Morris said that while some professors attribute alterations in engagement and academic standing to the credit change, some find it hard to separate from the current political and health crises throughout the last three years.

“I have heard of many faculty noticing a decreased student engagement, but I don’t know if that can be applied to the switch,” Feltrin-Morris said. “Outside factors and a sense of weariness may be present.”

Freitag said most professors’ main concern is the academic schedule for classes next semester, as the current grid that classes are supposed to run on is not in use and needs to be fixed.

“There’s a kinda overhaul of the grid system that is happening,” Freitag said. “We’re trying to meet the proper amount of minutes required for the New York State education purposes. … My understanding is that there is work on how classes are fitting together now and to make a new master grid that works with the longer classes.”

Kolberg said that adhering more to the grid system may engage students more and help fix the problems seen with the current workload.

“It hasn’t even been adjusting our classes to the delivery, it’s about scheduling, which is a nightmare,” Feltrin-Morris said. “If you teach 70 minutes like I do, you inevitably end up 10 minutes over and so students then have a hard time registering for another class.”