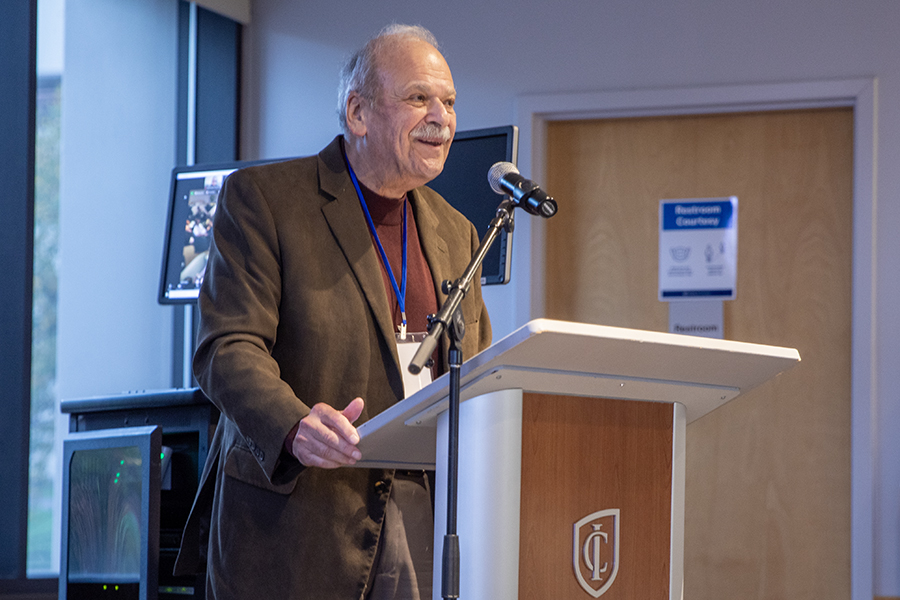

Martin L. Brownstein, retired associate professor in the Department of Politics, received the James J. Whalen Meritorious Service Award on Oct. 28 for his longtime commitment to Ithaca College.

Brownstein worked at the college for 40 years; he started teaching in 1970 and retired in 2010. He founded an internship that took students to Washington D.C, and taught courses in media and politics, legislative policies and personality and politics.

When Brownstein came out as gay in 1976, he also merged the college’s political curriculum with aspects of his own identity with courses like political theory and gay politics. In 1983, he served as the first faculty adviser for the Model UN team until he retired. At an event held by the Department of Politics on Oct. 27, alumni celebrated Brownstein’s impact on the college and on his students.

Contributing writer Jacquelyn Reaves spoke with Brownstein about his time as an associate professor of politics, how he lives his life within his multiple identities and his experience teaching for 40 years.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jacquelyn Reaves: How has your identity impacted the work you do?

Martin Brownstein: It informs just about everything. When you grow up within a minority culture, it frames your whole worldview. And I live not only within one subculture but two, and I live at the margins of those. So, I’m not fully connected with the gay world. I’m not fully connected with the Jewish world. I’m dancing on the line between them. And how I look at the world generally as a marginal person … defines my life, it defines my teaching [and] it defines my work altogether. There are two lenses I look at life through. I have tri-vision or something like that. There’s always a sense of being on the margins. That’s probably the best way to put it.

JR: What was the importance of you receiving the James J. Whalen Meritorious Service Award?

MB: I think it’s very significant. Whalen was here for a very long time. I actually saw him being interviewed in 1974. He reshaped the college. He surely reshaped my career. I was tenured under President Whalen. And he and I had a relationship that began stiffly because he and the faculty were at odds, notably over unionization. So, we began with some degree of stiffness, but he understood that I was a positive presence on campus. We didn’t come attached as friends, but we warmed up to each other. The fact that he was president, the fact that I was so marginal and we coexisted in a group, that’s significant for me. I think it might have been a little bit for him, and certainly for the college. I feel very warm and grateful for the recognition and reconciliation from the college.

JR: How would you say that students evolved from when you first started teaching to when you retired?

MB: It was a pretty radical and transformative time and so most of the students were very experimental in their lives, very willing to move. Big, new thoughts. That’s the time they were living in. By the time I left, [students] got much more careerist, much more concerned about payments of college and college debt. Those issues were there but they were there at lower levels. Students notably have become much more nervous about the economics of college life.

JR: What were some challenges you faced in your career?

MB: Notably, I received tenure without a PhD and without publication. I was a bad boy, an activist bad boy. And what prevailed … what I was hanging on to, was that students wanted me there. That was all a challenge in my probationary years. [My first years] were very fiery, very exciting. To consider me a permanent member of the Ithaca College community took some doing on a part of a lot of people. People have considered me as somewhat of an oddball case. In a variety of ways that was true. That was true in my department, at the college level and it was true for a lot of students. Of course, once I came out, everybody had to reconsider me again. Every day, people who thought they knew me had to reconceive who they thought I was. I had to reconceive how I thought of them as friends. And I lost and gained a lot of friends in my life. But I always had two big challenges: the absence of a degree and then coming out.

JR: What do you think is the importance of having discussions and having an exchange of ideas between teachers and students in an educational setting?

MB: It is used in the places where it’s most obvious: liberal arts classes, literature classes [and] politics classes. I think open discussion and that sense of open discourse for interaction between faculty and students lies at the center of mathematics. It lies at the center of physics. It lies at the center of business. To keep potent conversation alive, it’s among the top things that any successful teacher has to present the information from the podium in order to encourage you or inspire any marginal student. A lot of our students are not terribly happy about their high school lives. A lot of our students come from next-to-broken families or carry a lot of tragedy around with them. The job of a teacher is to energize that class. It doesn’t matter what people say, but if they’re talking to each other on a continuing, conversational basis, that centrally opens inquiry for all. I would frame my classes so that I would always start off with a question that was formal. I would come back to that question in the last five or 10 minutes in almost all of my classes I would let [discussion flow]. In my bigger classes, the phrase that would open up the discussion was from the movie “Network”: “I’m mad as hell. I can’t take it anymore.” The conversation would start instantly, and it wouldn’t stop for 30 minutes until I had a chance to reframe it.

Mitch Feder • Nov 17, 2023 at 1:16 pm

Marty is one of a kind. I took as many classes as I could with him in my time at Ithaca. He’s a knowledgeable and inspiring educator. I’m glad he received this well deserved honor.

Louis Frankenthaler • Nov 17, 2023 at 12:27 am

A wonderful interview with a person who helped to make IC a place in which one can be political… In my days (84-88) Ithaca College was not the most politically active. There was too much apathy, but Marty helped to create space for political discourse, protest and presence, regardless if one was from the right or the left.