The Ithacan’s three-part package on unionization on college campuses:

- Part One: Colleges weigh-in on value of unions

- Part Two: Part-time faculty across the nation move toward unionization

- Part Three: Colleges increase use of adjunct faculty as their role evolves

See The Ithacan’s editorial:

Colleges weigh-in on value of unions

With Ithaca College announcing small salary increments and a special all-college meeting to discuss ways to cut back, some employees are concerned with job security. Across higher education, unions have proven to be an option to address similar concerns.

The all-college meeting will be held March 5, in which President Tom Rochon will discuss ways the college can save money. Discussions over how the administration is planning to cut back and the prospect of part-time faculty members at the college potentially establishing a union have brought up questions of how unions function on college campuses.

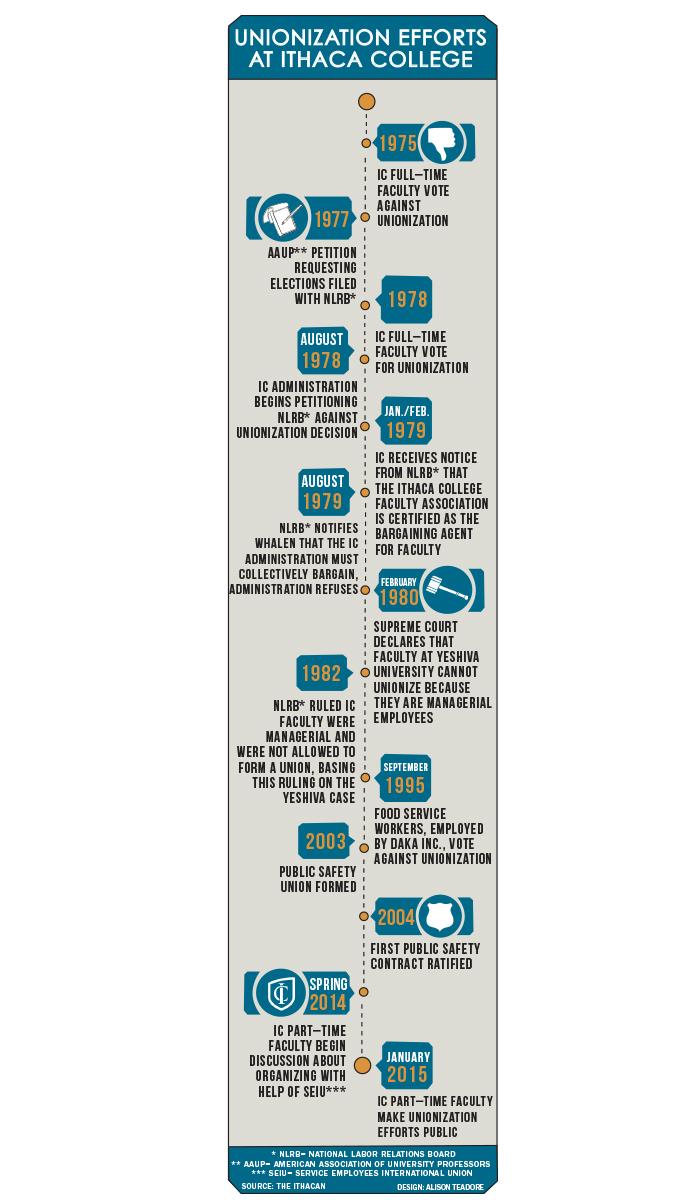

The Office of Public Safety and Emergency Management is the only group on campus to have successfully unionized. Full-time faculty voted to unionize in the late 1970s and early 1980s but were ruled to have enough say in the management of the college that they were not considered laborers but rather managers, under the Supreme Court’s 1980 Yeshiva ruling, thus rendering them ineligible.

In past years, staff members have also discussed unionization, but staff members who preferred to remain anonymous said they are too afraid of losing their jobs to talk about unionizing today.

“They don’t like us using the U-word,” a staff member said. “Anytime anyone brings it up, other people just say, ‘shhh.’”

Another staff member said the culture of staff treatment has changed over the past few decades.

“When I started here, it was more like a family atmosphere,” the person said. “Now it’s more like a business atmosphere. They’re just looking at dollars and cents. They’re not looking at people as people.”

Public Safety formed its union with the United Government Security Officers of America in 2003. The union has a membership of 29 out of 41 total Public Safety officers, and the current bargaining unit employees include non-sworn security officers, sworn patrol officer and patrol supervisors, communication specialists and parking services employees.

Laurenda Denmark, the secretary of the college’s Public Safety union, declined to comment.

When the union formed, then-President Peggy Ryan Williams said in an Intercom statement she was concerned about collective bargaining.

“I am disappointed that our Public Safety employees have decided to have an outside labor organization speak for them on all employment-related matters,” she said. “We have not had any unions at Ithaca College because the college is viewed by most as a good place to work, and the majority of employees have concluded that they are better off maintaining a direct working relationship with their supervisors, managers and administrators.”

One of the anonymous staff members said at the time Public Safety was moving to unionize, other staff members — custodial, maintenance — used to have more conversations about unionizing, though the atmosphere was not welcoming to it.

“It’s always been we’ve been threatened with our jobs because of it,” the source said.

Staff at Ithaca College have tried to unionize in the past. Food Service workers voted against unionization in 1995 amid allegations by union organizers of intimidation by DAKA, Inc, the food service provider at the time, which DAKA denied.

By comparison, there are seven collective bargaining groups at Cornell University. Professionals unionized on Cornell’s campus include carpenters, electricians, plumbers, Public Safety officers, engineers, custodial, food service, bus drivers, grounds workers and adjunct faculty in the Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations. These professionals collectively bargain in various unions: the Tompkins-Cortland Counties Building Trades Council; Communications Workers of America; the Cornell Police Union; International Union of Operating Engineers; United Auto Workers; International Security, Police and Fire Professionals of America; and Cornell Adjunct Faculty Alliance.

Cornell Graduate Students United has begun to push for collective bargaining and may appeal a National Labor Relations Board ruling from 2002, which ruled that student workers on college campuses do not classify as workers under the National Labor Act.

Cornell’s agreement with the UAW union covers service and maintenance occupations including custodians, food service workers and maintenance mechanics. According to the 2012–16 agreement between Cornell and the Cornell Service and Maintenance Unit United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America Local 2300, all service workers at Cornell make at least $14.58 an hour.

Pete Meyers, the coordinator of the Tompkins County Workers’ Center, said this was an impressive rate for the over 1,200 service workers at Cornell.

“None of these workers are making less than $14.50 an hour, which is incredible, given the fact that a food service worker in town could be making $9 an hour but are guaranteed at least $14.50 at Cornell,” he said.

Mark Coldren, associate vice president of human resources, said the college does not disclose salary information of faculty or staff outside of the hiring process.

Nancy Pringle, vice president for human and legal resources and the general counsel secretary to the board of trustees at Ithaca College, said it is difficult to be able to predict the long-term effects of unionization.

“The realities of collective bargaining is that it is an inherently time-consuming process involving trade-offs, which impact all parties engaged in the process,” Pringle said.

Terry Sharpe, the president of the local branch of the United Automobile Workers and a former food service worker at Cornell, said she would encourage other staff members to unionize.

“If you ask a handful of people, they are probably feeling the same thing… when you stand together united, it may be easier to gain the things you need,” she said.

However, Bruce Cameron, the Reed Larson professor of labor law at the Regent University School of Law, said labor unions are straying from their original missions by unionizing on college campuses.

“Consider the original reason for labor unions — to fight greedy and mean-spirited employers who were not smart enough to realize that happy employees are more productive employees,” he said. “Are those running universities motivated by greed? Are they mean-spirited? Stupid? Of course not. … No one is getting rich at the expense of the workers.”

John Scully, an attorney with the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, agreed that the traditional purposes of a union are not relevant at a college or university.

“Unionization cuts at the very heart of the very nature of a university, which as a unique institution, the shop floor cannot be imported onto,” he said. “Unionization, even if it doesn’t immediately do this, has the latent threat of interfering with academic freedom and freedom of speech, two of the hallmarks of a traditional university.”

Cameron said unions hurt free speech because unions bar nonmembers from having a voice in working conditions, and faculty members who do not want to pay union dues would find themselves without a say in working conditions.

“The union is the exclusive bargaining representative — you are not allowed to speak for yourself with your employer regarding your wages and working conditions,” he said. “The union negotiates average wages. If you are better than average, then the union harms you.”

Risa Lieberwitz, a professor in the Cornell University School of Industrial Labor Relations said an advantage of unionization is providing employees with increased job security, as employers are required to show “just cause” for firing employees in a union.

It is common for colleges and universities to push back when faculty or staff move to unionize, William Herbert, director of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions at Hunter College in the City University of New York, said, often through the form of sending letters expressing concerns to the parties moving toward unionization.

Lieberwitz said most employers fear losing control over employees if they decide to form a union.

“Most employers would like to have unilateral, top-down control over their workforce,” she said. “I don’t think it’s about the money. If people unionize there will be some redistribution of wealth … [but] I think the primary reason employers resist unionization is because they do not want to have to bargain with the union and they want to have unilateral control.”

Pringle said the administration acknowledges that a unionization effort is the choice of the employees involved.

“The college recognizes that unionization is a matter of choice for employees, not to college administration or outside third parties,” she said. “In the event the majority of part-time employees unionize, the college will bargain in good faith in full compliance with the law.”

Cameron said most administrations don’t want unions because unions restrict institutions from accomplishing their educational goals.

“University management tries to stop unions for the same reasons most companies do not want a union,” he said. “It limits flexibility in resolving workplace problems. It rewards mediocrity. It makes it harder to financially reward superior research and teaching. “

Ronald Ehrenberg, the director of the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute in the Cornell University School of ILR, said administrations at many private colleges and universities simply are not used to dealing with unions on their campuses.

“Especially in private education, they are not used to dealing with collective bargaining with tenured and tenure-track faculty because that is prohibited by the Supreme Court’s Yeshiva decision, which said tenure-track faculty behave like managers and are not allowed to participate in collective bargaining,” he said.

Ithaca College’s full-time faculty petitioned to unionize in 1977, and the National Labor Relations Board ruled that full-time faculty were able to unionize. In 1979, the faculty voted to unionize. However, the administration at the time, led by then-President James J. Whalen, refused to recognize the union. In 1982, the NLRB adopted the same mentality, influenced by the Yeshiva case, and ruled that faculty at the college were not allowed to unionize.

In recent years, however, Leiberwitz said the NLRB has started to interpret the Yeshiva ruling in a different way. In particular, she said, the National Labor Relations Board ruled in the Pacific Lutheran case in December 2014 that they would start to determine on a case-by-case basis whether or not the faculty at private institutions are actually managerial employees.

“They decided they are going to emphasize the factors that had to do with just how much actual control faculty have as a group over policy decisions and decisions that affect the university as a whole,” she said.

Faculty and staff at the college are invited to and may choose to express their concerns at President Tom Rochon’s special all-college meeting at noon March 5 in Textor 102, where he will present their salary increments and means of saving money as an institution.

Part-time faculty across the nation move toward unionization

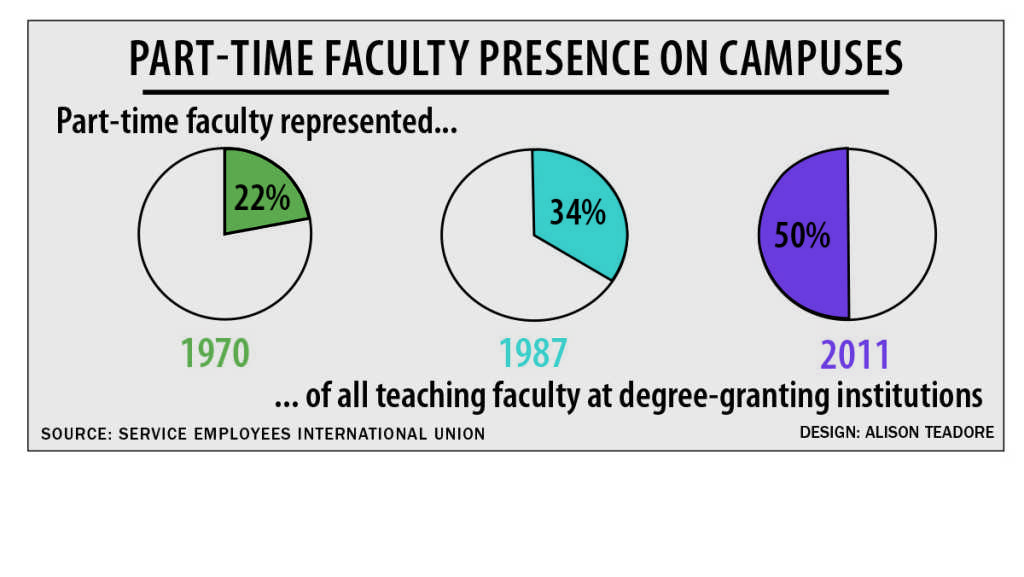

As part-time faculty members at Ithaca College gain support in their move toward unionization, they fall in line with a national trend.

Labor organizers, particularly with the Service Employees International Union’s Adjunct Action initiative, have helped adjuncts and part-time professors at other colleges and universities to unionize, including Georgetown University, Tufts University and Northeastern University. The SEIU is currently helping the part-time faculty at Ithaca College move toward unionization. There are currently over 22,000 adjuncts and part-time faculty members in unions with the SEIU, according to the organization’s website.

According to the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions at Hunter College in the City University of New York, most schools where adjuncts vote to unionize, the vote passes and the union is formed. Since January 2013, there have been 41 successful unionization votes for faculty and grad student unions while only two unsuccessful votes and five petitions were withdrawn prior to votes.

Ithaca college’s part-time faculty did not participate in a “National Adjunct Walkout Day” Feb. 25, although they supported the adjuncts who did walk out across the country. Brody Burroughs, a lecturer in the art department at the college and one of the organizers of the recent unionization movement at the college, said walking out would be counterproductive to the their unionization efforts, which are constructive and long-term.

The national increase in non–tenure track faculty has created an atmosphere in which these faculty would be interested in negotiating with the administration, known as collective bargaining, Risa Lieberwitz, a professor in Cornell University’s Industrial and Labor Relations School, said.

“With this explosion in the number of non–tenure track faculty … many of them are very poorly paid, and if you put that together with the job insecurity that they have, they have a great interest in thinking about how they improve their working conditions,” Lieberwitz said.

Improved working conditions are common in cases where part-time faculty unionize, which has occurred more often in the public sector, William A. Herbert, director of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions at Hunter College in the City University of New York, said.

“It would be fair to say that faculty who have been unionized in the public sector have a very different package of benefits that resulted from collective bargaining,” Herbert said.

But improvements in benefits may not be worth it, John Scully, an attorney with the National Right to Work Foundation, said. Scully has written amicus briefs on several aspects of unionization in university settings. He said the level playing field of unionization makes it difficult for superior professors to stand out.

“The professor with a particular specialty, knowledge or expertise or ability to teach is treated the same way as someone who might be at the bottom of the ladder,” Scully said. “Unionization would reduce their compensation to the level of someone who is just picked up because that is all the university could find to fill that position.”

Rachel Kaufman, a part-time lecturer in the writing department, said forming a union would provide a voice for them that she said they currently do not have.

“That would be a voice not just to address things that we have concerns about right now in the spring of 2015, but it would be an ongoing voice that could respond to issues as they arise at the college in the future,” she said.

Rachel Kaufman is a lecturer in the Department of Writing.

Though unionization does often improve wages and working conditions for adjuncts, the institution has to find a way to pay for it, Ronald Ehrenberg, the director of the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute in the ILR School, said.

“Most private universities do not have large endowments, and their budgets are very, very tuition dependent, so if costs go up because of higher wages for faculty, then ultimately students will be paying for it in the form of higher tuition,” Ehrenberg said.

Herbert said, however, adjuncts make so little money per course, the net effect of giving them slight increases in pay would not have a net impact on students.

“Right now, the level of salary for non–tenure track faculty is generally between $1,500 to $5,000 per course depending on the college or university,” Herbert said. “I don’t think the amount of increase that would be involved in raising the salaries from that point would necessarily impact tuition.”

At Ithaca College, part-time professors are currently paid $1,300 per credit hour.

Ehrenberg said schools where adjuncts have been successful in forming a union are often wealthy schools that have the fiscal ability to raise compensation and schools in urban areas with a large pool of adjuncts.

At Tufts, the SEIU helped organize adjuncts and other part-time professors who later voted to form a union and then entered negotiations with the administration. On Oct. 24, 2014, the part-time lecturers voted to ratify a contract, which gave most of the part-time faculty a 22-percent raise; benefits to those teaching more than three courses during an academic year; and one-year, two-year, or three-year contracts.

Rebecca K. Gibson, a lecturer at Tufts and a member of the organizing committee, said the negotiations were very successful.

“The Tufts administration, for the most part, proceeded in a very dignified way with us,” she said. “We have a very good contract.”

Kim Thurler, director of Public Relations at Tufts, said the new contracts resolved important issues while strengthening Tuft’s ability to evaluate the performance of part-time lecturers.

“We are extremely pleased that this contract balances the needs and priorities of the lecturers and the university,” she said. “Our negotiations were focused on ensuring that our part-time faculty recognize that we respect the work they do for Tufts and their contributions to our educational mission.”

Gibson said students played a major role in supporting the part-time faculty and putting pressure on the administration, even holding a march during negotiations.

“I’m sure they tipped the balance,” Gibson said. “The fact that so many of them cared was embarrassing for the administration but also revealing.”

Adjuncts don’t always vote for unionization. In the spring of 2013, adjuncts at Bentley voted against unionization in a 100 to 98 vote. More recently, however, adjuncts voted to unionize in a second campaign Feb. 27.

Joan Atlas, an adjunct at Bentley University and a member of the school’s organizing committee, said Bentley’s conservative leanings as a business school as well as a forceful pushback from administration played into the failure of the first vote.

“The first campaign was vicious,” she said. “They have fought against it.”

Atlas said there were many letters from the president’s office and the provost’s office to adjunct faculty during the first campaign which often expressed the administration’s concerns about unionization.

Michele Walsh, director of News and Communications for Bentley, said the vote accurately reflected the adjuncts’ views of unionization at the time after a fruitful discussion of the situation.

“The union did not receive a majority of the ballots cast and counted, and therefore there will not be an outside third party representing our adjunct faculty,” she said. “As one of the few universities where adjuncts have representation on the faculty senate and are an integral part of the faculty, we believe this is the right result for Bentley.”

After the second vote, Bentley’s administration released a statement saying though they thought the result was not the right result for Bentley, they would negotiate in good faith with the union.

As the part-time faculty at Ithaca College move forward with their unionization efforts, Kaufman said she is unsure of what the administration’s response will be given that they have only issued one public statement thus far.

“Because that’s the only response we’ve gotten so far, we don’t know what to expect,” she said. “We do know what our rights are, and we expect that IC, being a pretty sophisticated institution, also knows what our rights are. We expect that everything will be dealt with above board, but beyond that, we’ll just have to wait and see what the administration’s response is.”

Colleges increase use of adjunct faculty as their role evolves

As the National Adjunct Walkout Day took place at colleges and universities across the country on Feb. 25, part-time faculty at Ithaca College did not walk out, choosing to instead wear buttons and stickers and educate students on what exactly the role is of part-time professors on college campuses.

The part-time position, or adjunct positions as it is referred to at other institutions, began as an opportunity for professionals in the field to come into the college setting to teach a course or two within the realm of their expertise, with the college paying them by the course, Rachel Kaufman, a part-time professor of the writing department, said.

“It’s a post that’s set up so that somebody from the community who has a whole career in the community outside of academia, can come into academia and share their knowledge … in a class, maybe in a seminar for students in that major,” Kaufman said. “And that’s a valuable thing to have somebody come in from their career and do that and just teach one class.”

Sean Themea, a junior communication studies major, said this use of the part-time position was beneficial in a class he took with Todd Livingston last spring, called Legal Environment of Business. Livingston had had a private law firm in Ithaca.

“I enjoyed learning from a person whose career lens was outside of pure academia, as he was able to blend the course material with real-world application,” Themea said.

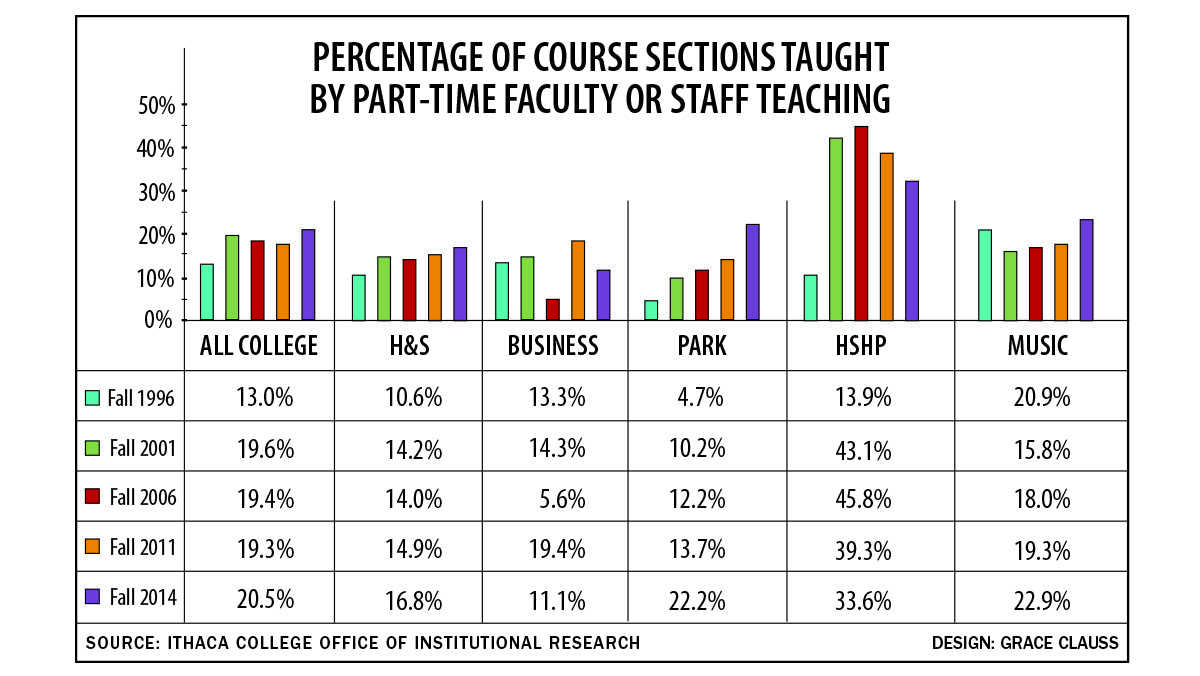

According to data from the Office of Institutional Research, since 1996 the percentage of faculty who are part-time or staff teaching at the college has grown from 20.4 percent to 35.5 percent, an increase that is reflective of national trends. According to the U.S. Department of Education, the number of part-time faculty has grown by more than 300 percent from 1975 to 2011.

Kaufman said this growth represents the way in which most part-time faculty are used by colleges today. She said colleges and universities use the part-time position as a loophole to hire teachers for core courses and pay them less than what they would have to pay a full-time or tenured faculty member.

“There was actually a valid function for the adjunct to serve at the beginning, and then administrations across the country facing tight budgets and really difficult decisions basically saw that as a loophole as a way to pay their faculty less,” Kaufman said.

However, Vice President and General Counsel Nancy Pringle said the number of part-time faculty at the college is below the national average. In 2010, American Academic released survey results that revealed that nationwide, part-time faculty made up 47 percent of all faculty in higher education, whereas around that time at the college only 31.5 percent of the faculty were part-time.

Pringle said the college hires part-time faculty for a number of reasons, including to provide more specific instruction.

“Part-time faculty are employed for a variety of reasons including, but not limited to, specialized instruction for a particular subject area not covered by full-time faculty, overload demands for a particular course, courses in the New York City and LA Centers, sabbatic replacement and leaves of absence taken by full-time faculty,” Pringle said.

Part-time professors at the college are paid $3,900 per three-credit course, or $1,300 per credit hour, and are only allowed to teach two courses per semester at the college. Michael Smith, an associate professor in the history department who is in support of the part-time professors unionizing, said the college has this cap on courses per semester because that would classify the part-time professors as more than half-time professors, thus requiring the institution to compensate them with health benefits.

He also said colleges and universities typically prefer to keep part-time professors in their part-time positions so as to not have to grant them the benefits full-time professors have.

“This is part of the game that the administration plays,” Smith said. “They want to avoid paying benefits, so they keep them at that level.”

Only being able to teach two courses a semester for $3,900 each often drives many part-time professors to teach at multiple institutions. For example, Kaufman teaches at Ithaca College, Elmira College and during the summer and winter sessions at SUNY Binghamton, for which she is currently designing classes for the summer program. She has also taught at Tompkins Cortland Community College in the past.

Kaufman lives in Owego, New York, and commutes 45 minutes each way to the institutions at which she teaches, constituting an hour and half each day, four days a week. She is also driving to Binghamton, New York, to begin publicizing her summer courses, but she said the institution may decide to cut those courses before the summer begins.

“I’m starting to build those courses even though I’m very aware that they may get cancelled the day before I go to teach them,” she said. “Even though I have built the entire thing already, I may not get paid for that at all.”

Kaufman said this unpredictability is one of the biggest challenges part-time faculty face. She said since part-time professors work on a semester-by-semester basis, it is difficult to know whether they will have a job from one semester to the next.

She said another obstacle part-time teaching presents is a lack of availability to meet with students in person, due to limited time and the inconvenience of having a shared office or no office space at all.

“I’d like to be able to offer more in support, both academic and just the kind of mentoring support that a faculty member should be able to offer, and I feel how I am less able to do that than I would be if I were better resourced, so a lot of my struggle is feeling how I could be doing better if I had the resources that I need to do it,” she said.

Dominick Recckio, a junior communications management and design major, said part-time professors’ lack of availability to meet in person is a big problem that the college doesn’t always take into account.

“They have to have limited office hours because they’re only getting paid to do so much, so meeting with students and actually providing their knowledge and services to those students is not easy, from their perspective,” Recckio said. “But I demand their time, and other students demand their time, and they should get it because we go to this college, so we should have our professors’ time.”

Smith said the general process to move up in the faculty hierarchy at institutions is often difficult. He said the first step would be that a professor would probably receive a full-time position that is not tenure-eligible, which entails term contracts of one to three years and a workload of four courses per semester, rather than three, which is typical for tenured and tenure-eligible faculty.

He said many departments at the college have at least one and sometimes up to three or four people in NTEN, or non–tenure eligible, positions.

If the faculty member wishes to move up, the next step is to apply for a different position that is tenure-eligible. Once hired as a tenure-eligible faculty member, they would have to go through another process for several years, after which they would either be granted tenure or not.

Bruce Cameron, Reed Larson professor of labor law at the Regent University School of Law, said though there are some decent non–tenure track faculty and some less-decent tenured faculty, part-time professors in general are people who cannot land a tenure-track job.

“Why is that? It is because someone made the judgment that their teaching would be of lesser quality?” Cameron said. “On the other hand, a tenured professor is focused on teaching, and his or her peers and management have decided that they are worthy of tenure.”

Junior Allison Dethmers said she had a subpar experience with a part-time professor, with whom she took Research and Statistics. She said the class was not productive, as the professor was not interactive or engaging.

“Nobody would really pay attention because he wouldn’t stand up and interact,” she said. “And then at the end of the semester, when we had to do evaluations, he would show us pictures of his dogs and be like, ‘Just remember, I have a family, too. I need this job.’ He was basically bribing us to give him a good evaluation.”

Recckio said he finds there is a lack of communication among part-time faculty and the administration, which has contributed to overlap to take place in course material, causing repetition for students.

Another issue, Kaufman said, is that part-time faculty are highly under-resourced and subsequently are not typically able to conduct faculty research or access professional development funds.

“Full-timers are quite busy, but we don’t have as much extra time as they do to keep ourselves as appraised in the latest developments in our field, to do research, to do the things that enrich the classroom in very real, albeit, somewhat more indirect ways like research and writing and professional development,” Kaufman said.

Smith said he understands these challenges from his experience as a part-time professor in the past.

“The hope is that for all of these folks is that somewhere there will be a full-time position eventually if they just keep doing this. It’s increasingly unlikely in the current environment of higher education,” he said. “So that’s why I believe that at least while they’re going to be doing this, they should get what would constitute a living wage for it.”

Kaufman said when she tallied up her W-2s, she found she made under the living wage in Tompkins County for a single person without children, which is equivalent to $21,382 annually before taxes, and less than half the living wage for a single person with a child, which is $45,146 annually before taxes.

James Eavenson, a lecturer in the Department of Health Promotion and Physical Education who teaches yoga at the college, said he did not go into part-time teaching to make money. He said based on experiences he has had in India, he finds people in the United States always seem to want more.

“I know that in the West, there is a deeply rooted unhappiness,” he said. “Nothing’s enough. We don’t have enough. We all need more to be OK.”

James Eavenson, a lecturer in the Department of Health Promotion and Physical Education who teaches yoga at the college.

He said he finds this mentality to be present in the unionization efforts of part-time faculty. While he is not against the movement, he is not currently involved.

“I have no stance on what other people do,” Eavenson said. “There’s that old statement: ‘If you’re not with us, you’re against us.’ That’s not me.”

The goal of the unionization movement is to give part-time faculty more of a voice surrounding these issues, and part-time faculty hope to educate students on these issues in the coming weeks through a teach-in, Kaufman said.

She also said part-time faculty hope to make the position more sustainable by unionizing to increase the quality of education for their students.

“I definitely don’t see that I want to be doing this, if conditions don’t change, and we’re trying to form this union so we can change them. But if they don’t change, I don’t think that I’ll be able to stay in this career for a long time, and I don’t see that many younger people going into this career,” Kaufman said. “Without this being a sustainable position, then higher education becomes unsustainable, so we’re really trying to raise up the whole system.”