A Meeting With Quetzalcoatl

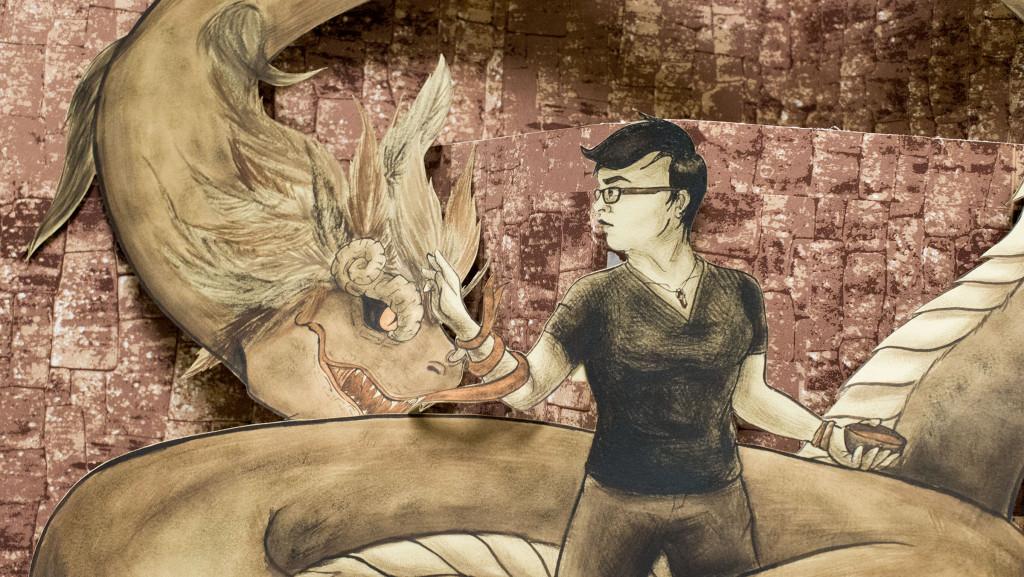

Almost instantaneously, it appears before her. Natalie Lazo is engulfed by the body of a feathered serpent. She has summoned the Mayan deity, Quetzalcoatl, revered for centuries by the Mesoamerican people and one of many gods idolized in their culture — a creature thousands have killed in the name of and sacrificed for. It is the patron of priests, god of the morning and evening star, inventor of books and the calendar, and the symbol of death and resurrection.

A seemingly intangible presence, its entire, otherworldly form dwarfs her 5-foot-2 frame and thick-rimmed glasses. It stares directly into her eyes, slowly curling itself closer toward her. Its long, slender tongue begins wrapping around her right hand, inviting her to move closer.

With a combination of trepidation and curiosity, she moves that same hand in its direction, slowly to its face. She’s about to make contact — real, tangible contact, with the plumed serpent.

[block]She has summoned the Mayan deity, Quetzalcoatl, revered for centuries by the Mesoamerican people and one of many gods idolized in their culture — a creature thousands have killed in the name of and sacrificed for.[/block]

Lazo pauses, looking back at the rough sketch in front of her. Before long, the piece will be coming to life in a grander form, capturing a scene in the eyes of its viewers who yearn to unearth more details.

“I want this one to be more personal,” she said. “It just shows up, and I’m put in this seemingly dangerous situation. This thing has its entire body wrapped around me, and my point is trying to make that connection, creation-of-man style.”

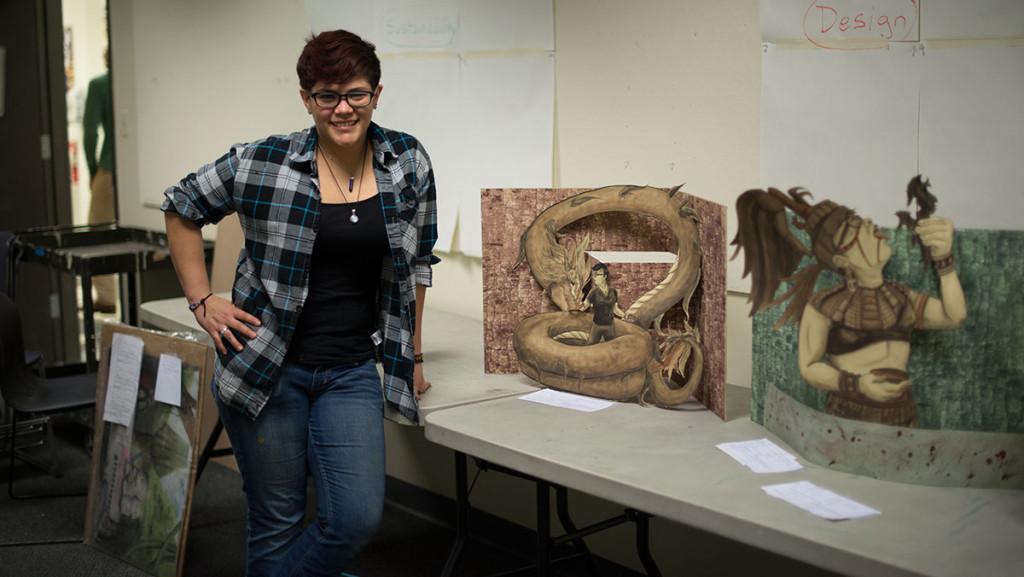

Under the mentorship of Susan Weisend, professor and chair of the Department of Art at Ithaca College, Lazo is in the developmental stages of her four pieces of artwork combining two- and three-dimensional elements for the 2015 Senior Student Show, beginning April 23 at the Handwerker Gallery. The works must be completed by March 16, when professors in the department, including Weisend, will judge the work and provide a thorough critique of her art.

Confined to a subsection of a studio in Ceracche Center along with four senior classmates, her workspace is no bigger than an office cubicle. From within, a thin sliver of window pane spreads across the top of the wall connected with the department’s parking lot outside, occasionally inviting sunlight into the room. Aside from that, the space is barren, save for the collection of works from the senior students in their respective segments.

However, within this compact space, Lazo continues creating larger-than-life pieces by means of depicting herself as the characters within them. As these personas, she intentionally gives herself present-day characteristics: Converse-brand glasses, beginning as a maroon red around the ears before eventually hitting a dark black once they encircle her eyes, matching her pitch-black eyeliner; and hair, cropped neatly above her eyebrows and following the contours of her outer lobes — ideal symbols of modernity.

The art is both an extension of her computer-based art, which she had completed in the fall semester, and a self-exploration of her Mayan ancestry.

“They’re all based off of Mayan culture, Mayan history and the connection that I have to that culture, despite being a first-generation American-born citizen,” she said. “I want to raise questions about it. I want people to talk about it and I want people to understand that this all existed and it’s still a culture, something that can be visited to this day.”

Lazo’s creative processes for the pieces were formed in the same, small sketchbook all of her works begin in, as a means to convey the initial concept within her mind. From there, she produces refined miniatures of the works in order to determine their feasibility on a grander scale.

The four pieces in the senior gallery will initially be drawn out in pencil before being completed with ink and brush. She uses a specific printmaking paper, French-made Rives BFK, as material for the two-dimensional elements. She methodically pats the brush down, accentuating sections of the art that demand more attention while combining several shades of black and brown.

“I’m using a mix of silk screening inks to get the colors that I want and making it with water,” she said. “It’s a very heavy-set paper, and it’s very sturdy.”

With so much time to be spent in the enclosed workspace refining her art, Lazo keeps a massive collection of bubble wrap from her shipment of printmaking paper adjacent to her unfinished works. When she’s feeling anxious, Lazo will pop the individual bubbles, alleviating the internal stress, if only temporarily. She leaves a note on top of the pile inviting her peers to follow suit.

“I’ve acknowledged that I’m not going to be sleeping much for the next couple of weeks,” she said.

For the three-dimensional sculptural aspects, she uses foam core as a backdrop to create a pop-out effect for the work. With the two-dimensional elements of the artworks as the primary focus, the foam core helps produce a more natural background for the pieces while also framing a scene for the work. In her piece with Quetzalcoatl, for instance, she will use the foam core as a three-dimensional backdrop for the serpent and herself.

“I really appreciate when my artwork can tell a story to a viewer and give them that experience,” she said. “These situations will have environments, so it will look like a snapshot.”

It will also be the culmination of four years of artwork in the department and an important stepping stone before joining the professional landscape, a course of action Weisend believes Lazo is well positioned for.

“As she’s progressed through her courses, her artwork has become more and more sophisticated,” Weisend said. “She has found her own voice, creative voice, in her artwork.”

Previously in the fall, Lazo worked on five pieces inspired by mythological creatures from around the world, including Quetzalcoatl. Broadly, though, the allure of such beings stemmed from Lazo’s deep-rooted curiosity to seek out more information. It became the aftermath of her appreciation for the mythological stories and worship that once comprised several now-dying cultures.

I really appreciate when my artwork can tell a story to a viewer and give them that experience. These situations will have environments, so it will look like a snapshot. [citation]Natalie Lazo[/citation]

“I wanted to make it tangible to my own mind and being able to recreate those things through my own lens of vision and from my research,” she said. “I might not be part of that culture specifically, but to be able to emulate the certain brush strokes or through a digital means in order to a convey a snapshot of some sort of illustrative moment in time in which these things existed … being able to pay back that reverence that doesn’t really exist anymore or as it used to, I think that’s my goal.”

The Mesoamerican Ballcourt

The ballcourt lies out in an open field, an area of spectacle and ritual. As the sun rises, its corresponding shadow slowly envelops the arena. Enclosed by stone blocks on two sides, an elevated view of the court from a cornice would indicate a gigantic I-shape. However, from the ground, a ball player has a much different vantage point. Her height allows Lazo to align with the two upraised mounds flanking her left and right. Directly above them, the stone walls obstruct a clear view of the sky.

Having donned a thin cloth around her torso, a daunting task awaits her. Made from the Para rubber tree, the ball used in the game exceeds seven pounds. Using only her hips, Lazo must hoist the rubber ball into a small, ring-shaped goal, 8 meters high. Her only allies are the hip guards augmented in an attempt to prevent further injury and a thick girdle wrapped in leather over her right shoulder.

In this game, life and death are on the line. Winners will be praised and presented with trophies, while the losers face subsequent decapitation, a customary sacrifice to the gods.

Lazo makes her way up the stone blocks, approaching the heightened goal. With one hand wrapped around the ring holding herself up, she lifts the dense ball toward its burdensome destination.

In the studio, Lazo uses a fine-tipped paintbrush to spotlight several areas of the ball player’s body, giving the image a more gestural element in its unmoving state. The ball player is dwarfed by the three-dimensional foam core background of the court. It helps create an awareness of the grand scale of the arena.

“My piece is more humorous ’cause it’s actually me just dangling off the top of it trying to get this ball into this hoop, which is impossible for someone like me to do, unless I lob it up and hope to God it gets through,” she said.

When working on her pieces, Lazo prefers to escape through music. For long sessions in the studio, up-tempo Spanish rumba-style music, such as that by the group Gipsy Kings, keeps her spirits lifted. It’s a reminder of El Salvador. It’s a reminder of home. Immediately, it becomes hypnotic.

She dips her paintbrush into the ink lightly, keeping in mind that oversaturating the brush will deter any advancements made on her piece. She works repeatedly on the same, small space of the art, dabbing the brush into the heavy-set paper more aggressively with each stroke. Each wipe is intentional and controlled. She will keep pressing until it aligns perfectly with the idea within her mind.

She momentarily steps back. She stares at the piece stoically, surveying the progress.

“There we go, that’s what I want.”

Her hands are spotted, but these aren’t natural pigments. They feature a combination of inks, oils and paint. It extends to her clothes, where navy blue jeans just a week old already feature a mustard-yellow smear, encompassing her entire knee like a crater.

“I don’t leave here without stains on everything,” she said. “I love what I do, so it’s worth it.”

Even so — being in a line of work that has a penchant for damaging items — she adorns herself with bracelets, rings and necklaces. The trinkets are worn interchangeably, except for her ultramarine necklace, made from the Afghan-based lapis lazuli stone, known for its intense, natural blue color. A gift from her mother, she never removes the thin, tetragonally-shaped pendant, regardless of the intensity of her work.

[block]She works repeatedly on the same, small space of the art, dabbing the brush into the heavy-set paper more aggressively with each stroke. Each wipe is intentional and controlled. She will keep pressing until it aligns perfectly with the idea within her mind.[/block]

In a machine-like rhythm, she moves back and forth between her art and her ink, only stopping occasionally to observe her headway. With the jewelry constantly moving with her, she enters a trance through the upbeat rhythms, a state in which she’ll complete five hours of manic work, even though it seems like only 20 minutes passed by.

“My mom says it’s the housework music,” she said. “When you need to do chores or something like that, music really gets you going. I love what I do because I’m allowed to do that sort of thing, and listening to music really does, for me anyways, put you in more of a zone.”

Though born and raised in the U.S., Lazo retains a deep appreciation for El Salvador, where both her parents are from and the majority of her family remains. While she hasn’t had the opportunity to return in eight years, the balmy regional weather, seemingly untouched countryside, tranquil waves of the Pacific Ocean overhanging from the beach and the warm, black volcanic sand caused by harmless, minuscule fragments of lava, constantly beckon her.

However, civil unrest spanning over a decade from the effects of the Salvadoran Civil War initially prompted her parents to raise Lazo and her two older brothers in Montville, New Jersey. Even now, the repercussions of the turmoil can be seen around her grandmother’s gated house, with the corresponding walls laced with barbed wire to deter any intruders. Outside, an armed guard is constantly on patrol, vigilantly scanning the block for anything and anybody out of place.

“As a kid you notice these things, but it doesn’t really hit you until later,” Lazo said. “But then growing up and being told about the civil problems that existed and how in the past my grandparents’ house had been broken into, it was a lot … our lives would’ve been completely different if we stayed there.”

There is no greater example of that than her own name. If she had remained, she would have most likely been named Natalia, but the move to New Jersey prompted her father to decide to change it to a more familiar American name, Natalie.

With the physical and emotional separation from the country, her mother, Martha, made it a point for Lazo to experience the culture she was missing in the U.S. She and her brothers ate traditional food and celebrated Latin American holidays such as the Day of the Dead. Spanish-speaking programs rang through their television. Most importantly, they were to speak English in school, but Spanish at home. In this language, stories were shared.

“I was reading to them tales from the country, tales from the culture, many stories about the ancestors,” Martha said. “They know everything — most of everything — of where we came from. That’s why I think she’s so into exploring more.”

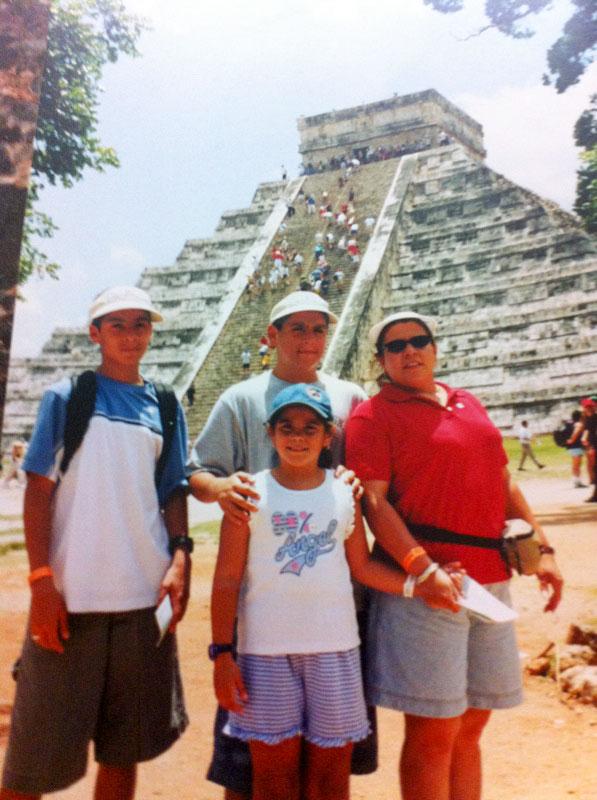

The Mayan exploration began in 2002. Lazo and her family traveled through Mayan ruins for about a week and a half. They followed the traditional Mayan route, beginning in El Salvador before going through Guatemala, Belize and Mexico. In Guatemala, she saw the well-preserved ancient city of Tikal, in the heart of the Guatemalan jungle.

The trip was rounded out with another time-honored city, Chichen Itza, in the Yucatan region of Mexico. It sits as a stark contrast to Tikal’s protected state, with an international airport 10 miles from the site. The relics are another two miles in length. Everything about it is monumental.

Lazo walked through the vastness of the Great Ballcourt of Chichen Itza. The entire arena reaches over 500 feet, and width from the stone walls on both ends reach an additional 225. Even as a child, she understood the massive court would always have the same effect on her if she had the chance to witness it again: sheer awe — awe at the scale of the court, and the ritualistic repercussions for those who compete.

“The hoops are still there,” she said. “It’s crazy what they had to do and to this day, the amount of physical demand for these players, it’s hard to even conceptualize now. Trying to imagine these people playing these games and knowing that lives were on the line, I feel like there’s a lot of residual emotion left there.”

The High Priestess’ Offering

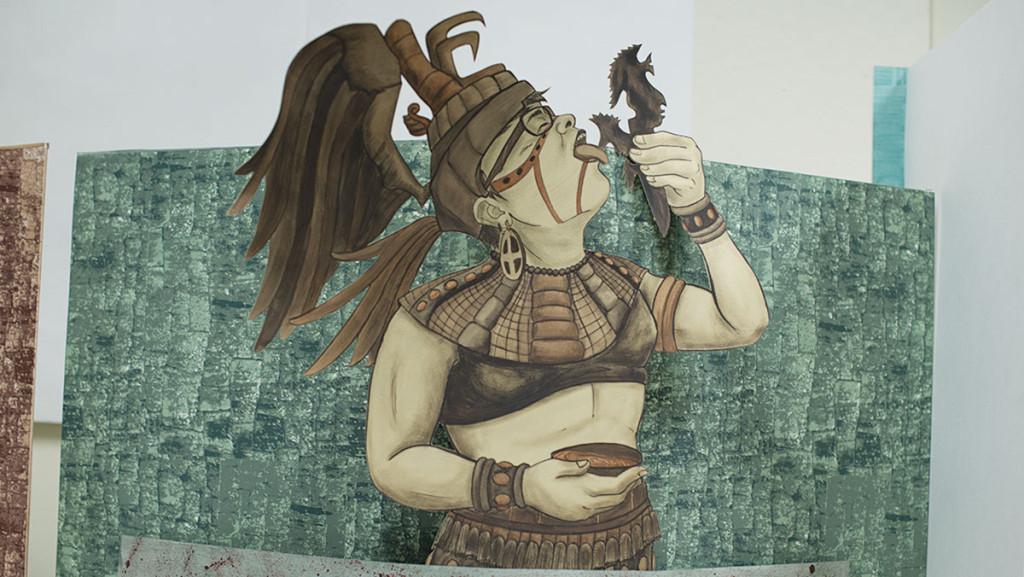

Lazo’s body is ornamented with feathers and jewelry, the conventional image of a high priestess. She holds an eccentric flint in her left hand: a black stone cut down and layered with several, distinctly sharp ridges. She has a bowl in her right hand, leaning it gently on the curvature of her torso. Now, she is ready to communicate with the gods, but in order to do so, she must first begin piercing her body with the flint.

Soon, the blood drawn and subsequently collected in the bowl will allow her to reach the proper medium to contact the deities. Willingly and without hesitation, she draws the flint closer toward her mouth, sticking out her tongue for the first of many incisions.

For the betterment of the civilization, the bloodletting will commence.

With an Amazon Fire tablet perched upright, giving her an online image as a reference, Lazo outlines the feathers behind the head of the priestess with her mechanical pencil. She wants to ensure the initial sketch of her final draft is a historically accurate representation of a Mayan priestess.

“That was their role in society,” she said. “Aside from being a very powerful leader, they’re also the ones expected to sacrifice themselves for the good of the rest of the people.”

Before beginning her freshman year at Montville Township High School, Lazo returned to El Salvador in the summer of 2007. While there, she began to explore the country further with her family. Of her own accord, she gleefully traveled through her homeland, across the bustling streets, malls and markets in San Salvador, the sunny, clear plains of the rural landscape and the thousands of hectares comprising the Salvadoran jungle.

In the expansive countryside, the Mayan traces were all but nonexistent. In their stead, churches plastered in ivory white paint lay scattered throughout the different villages as remnants of the Catholic Revolution of the 1800s. Above the steeples, a lone cross touches the endlessly clear, blue sky.

A Roman Catholic herself, Lazo’s religion is a stark contrast to that of the Mayans, whose culture dictated that sacrificing themselves to a higher power would bring better prospects to their people. Those tasked with this were customarily the high priests and priestesses. On occasion, when bloodletting, they would take a rope laced with thorns and run it across their tongue to lose blood swiftly, which likely induced hallucinations.

[block]For the betterment of the civilization, the bloodletting will commence.[/block]

Just as Martha emphasized and instilled contemporary Latin American culture to her, Lazo relays this gruesome information to her mother, who shares a similar interest in the cultures practices. With Lazo accurately and faithfully describing the rigid points of the flints, and the incisions the priests would undergo, Martha cringes with a combination of disgust and fascination. Their bond, among many other things, is cemented through curiosity.

“She took so much care to make sure that we were assimilated into our own culture as Hispanic-American people, for me it’s interesting ’cause now I’m coming back and teaching her all these things that we didn’t know,” Lazo said.

They see the value in paying reverence to something that no longer exists, but once dominated the landscape. There is an underlying importance in the ancestral culture.

“It’s a lot of rituals, a lot of thoughts that are related really deep with nature, that are related with how we developed as human beings, that there has to be a connection between everything,” Martha said. “It’s not just that we have to live. It’s because we are supposed to be connected with Mother Earth. We are supposed to be connected with the elements, we are supposed to be connected with our spirituality. If not, we are just abiding. We have to be whole in many ways.”

For Lazo, this desire lay dormant for years, waiting for the opportune point in time. It wasn’t until coming to Ithaca College, taking courses pertaining to Latin American studies, that the investigative interest in her Mayan roots was reignited.

It reemerged in September of 2014, when she traveled to Washington, D.C., with the art history department.

During the trip, they spent time at Dumbarton Oaks, an historical estate surrounded by trees, tucked away in suburban Georgetown. Two brick pillars flank its entrance, encompassing two black wrought-iron gates decorated with gold ornaments. They open to its sand-colored pebble path, ushering visitors to the front door of the restored mansion.

Within the Harvard University–run research institute lies an abundant collection of Byzantine, European and Pre-Columbian art. The works are displayed on plexiglass suspended in the middle of the room, creating an aura of elevation. This is complemented by natural light gleaming through the museum’s glass-heavy enclosure and a small garden in its central atrium, an organic environment reminiscent of the artwork’s origins.

Lazo walks through the exhibit excitedly, fueled by the sight of Mayan artifacts never seen beyond a computer screen or a textbook. In her state of elation, she feverishly asks the museum curator anything that comes to mind, from the alignment of the art to the specific time period of each artifact. She soaks up the knowledge like a sponge, ready to relay this information to anyone willing to listen. Internally, she relates almost everything to her Pre-Columbian arts course taught by Jennifer Jolly, associate professor and Latin American studies coordinator in the Department of Art History.

“It’s interesting. It’s not a course that I teach oriented around questions of contemporary identity,” Jolly said. “We don’t frame it in those terms, and yet there are students that have Latin American ancestry who are really curious about these other roots of civilization in the Americas.”

From there, Lazo could see similar motifs with the art displayed to the pieces she had previously seen in El Salvador. While not directly related to her own country, the crafts are connected through other modes of Latin American art throughout the region.

An identity was formed, forged along with her ever-growing spirit of inquiry.

“Identity is something that we build, and it’s this artificial construction,” Jolly said. “And yet we create it so it has this incredible meaning to us, and I think that speaks to it. It’s not that she has some kind of essential, everything goes back to El Salvador, it’s that she’s created a sense of meaning out of what’s available, which I think is a really empowering thing to do.”

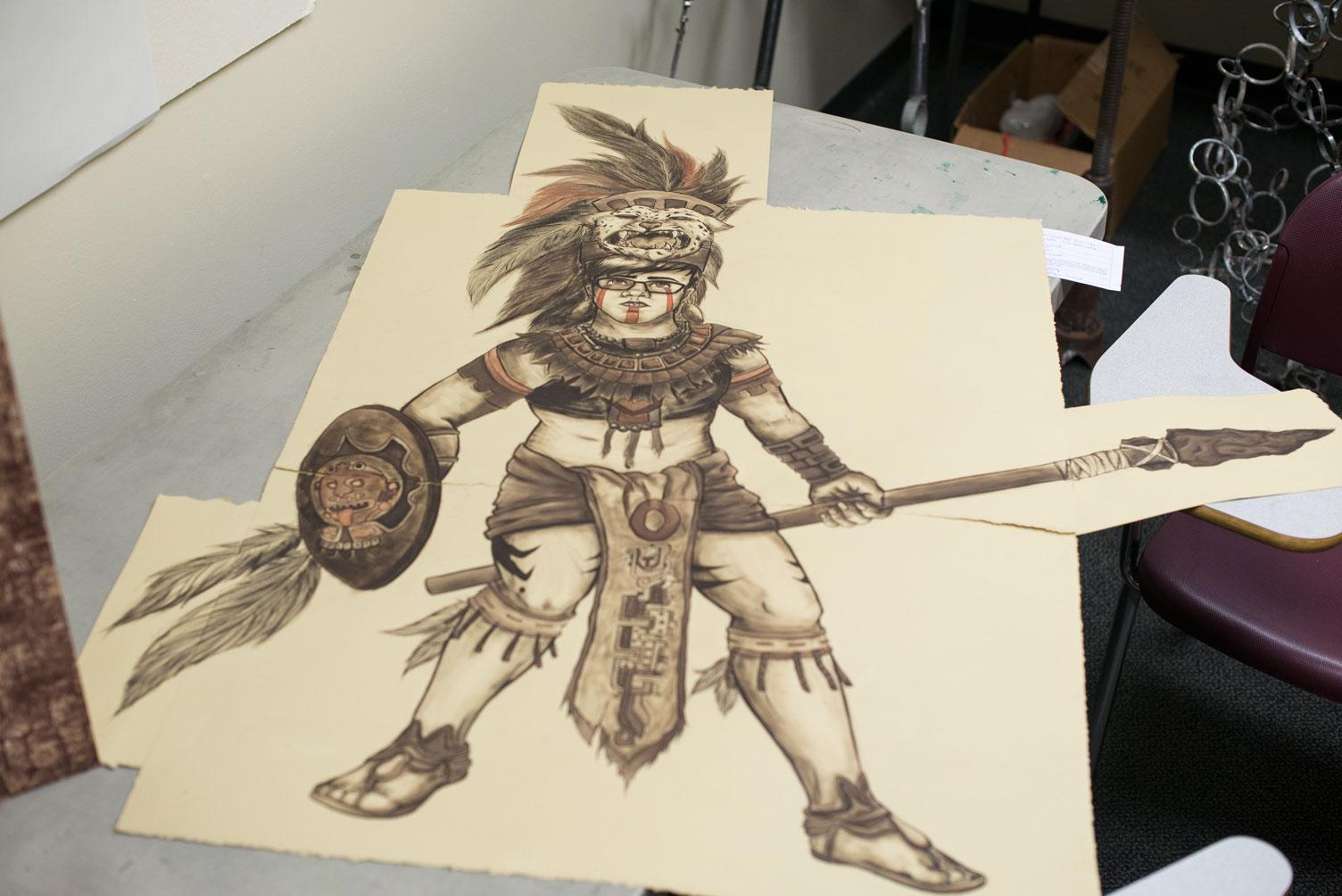

The Jaguar Warrior

Lazo’s body is the embodiment of war. It begins with the decapitated head of a jaguar balanced above her own, granting her strength in battle and eliciting fear in the eyes of her adversaries. Those eyes are focused on the task at hand, as her hair fails to obscure her view.

Three streaks of red run down her face: two from below her eyes and one under the chin. Large hoops hang from her ears. A combination of pelts and feathered garbs flow around her figure. A shield adjoined to feathers, along with a spear, are held firmly in hand.

Her front cloth bears the image of Quetzalcoatl, who will receive all the captives from battle as a sacrifice. The serpent’s power is to thank for her enhanced animalistic nature. She grips the spear tighter as she anticipates combat.

While working on the enlarged, refined version of the original sketch, Lazo ruffled the bristles of the brush to give the image a more tattered feel, an effect that correlates well with a Mayan warriors’ typical disposition.

“They were ruthless,” she said. “They would cut off heads and capture sacrifices if they weren’t already killed on the battlefield, just because they could.”

On Feb. 28, less than three weeks remain until Lazo must present her work to faculty of the art department for critique. She is in the basement of St. Paul’s United Methodist Church on North Aurora Street. She is surrounded by people in constant motion. The deadline is persistently looming over her. However, it’s a Saturday night, and she needs to unwind.

Lazo began swing dancing during her junior year. She joined the IC Swing Dance Club because she needed another physical outlet from her artwork, after spending her first two years on women’s crew.

“I used to do varsity rowing,” she said. “The commitment was way too much, so I stopped that. It was getting in the way of my academics and my art classes, which are at very concrete times.”

The basement’s wooden floor is the ideal platform for dancing. Djug Django, Ithaca’s local gypsy swing band, performs beside the crowd, invigorating the room with its upbeat rhythms. Lazo approaches unfamiliar faces in the crowd — from Cornell University students to members of the Ithaca Swing Dance Network, a grassroots organization to promote swing dance in the Ithaca area — inviting them to join her.

In these dances, she always leads. She enjoys guiding a partner, choosing the appropriate steps based on the tempo of each song. Leading a dance is a traditionally male role, but she finds a man willing to dance, and willing to follow. She begins directing him with each step and each beat. Everything is spontaneous. Everything is instinctual.

“It’s a very good shift from doing very hard-set artwork that needs to have a clear purpose,” she said. “That’s the biggest divide. [Art] is a very isolating process and to be able to step back from that process and go to something social, do something else that involves other people and is based on other people’s interactions with you, that’s a really good change.”

With the stress temporarily alleviated, Lazo returns to the studio to finish refining the Jaguar Warrior piece, which will not incorporate any three-dimensional foam core elements. Instead, it will be the largest work in the collection, spanning over 40 inches in height and width, entirely on her specialized printmaking paper.

[block]Lazo’s body is the embodiment of war.[/block]

Lazo tirelessly labors to refine the art, unwavering in her work ethic. She is determined to put in the necessary hours to leave a lasting impression in the eyes of any onlookers of her work.

“If I do a piece of artwork, or if I do a project or if I do anything, I try to put 110 percent into what I’m doing, because to me, half-assing something does not make sense,” she said. “My parents and my family have grown up with the idea of doing your best and putting in the hard work and effort to get to a point where you can stand back from your work and be proud.”

Regardless of the evaluative, critical outcome from her professors, in her mother’s eyes, Lazo has successfully retained an appreciation for her roots. Martha intentionally brought her children to Mayan ruins, and maintained a Latin American culture within their New Jersey household. Now, the two lifestyles have intertwined.

“She’s been living and comparing both worlds,” Martha said. “You see the culture that she has here in the United States, but she’s leaving, at the same time, that culture when she visits our home country. I think it’s part of her, that she has to be in both cultures in her life.”

Judgment Day

Lazo returns early from spring break to finish her artwork. The narrow halls of Cerrache, typically comprised of students and faculty, are uncharacteristically empty. In this isolation, she plays her music on computer speakers without the concern of bothering her peers, flooding the room with a melodious beat.

Now, she puts on the finishing touches. She holds a kneaded eraser in hand and presses it against her pieces, highlighting parts of her figures that need additional shading. Once satisfied with their undertones, she uses an X-ACTO blade to carefully cut her two-dimensional figures out and pastes them with a glue stick on the now-ready foam core backdrops.

Hours, not days, remain until her semester’s work is reviewed extensively. For Lazo, this is a period of anxiety, and anticipation.

“It’s exciting to know that this is a similar feel to what I’m going to be feeling in a month when all of this is put in exhibition and the opening happens, but it will be to the entire public and not just the people in the art department,” she said. “That’s equal parts nerve-racking but also super thrilling, and I think the fact that the prospect of that excites me is a really good sign, ’cause I’m confident in my work.”

With the pieces completed, Lazo moves them to a separate room on March 16 for the faculty of the art department to review. Before long, the professors will make a transition from art teachers to art critics. But, in order to do so, they must disconnect emotionally from the artwork made by students they have mentored and taught for the past four years and evaluate the work objectively as professionals.

For this reason, the faculty review the art without the presence of the students, who will be notified which pieces will be approved for the gallery if the artwork has their signed approval.

“It’s terrifying because they’re removing themselves from the position of professor to the professional artist that actually sees what your work is like based on talent and execution alone,” Lazo said. “They sit down and jury all of these pieces based off of their artistic merit, their composition, all of the standard artistic criteria.”

The following day, Lazo’s artwork lay in their finished states alongside an assortment of paintings, sculptures and photography from her peers in Ceracche 121. The slender, rectangular shaped room is windowless, preventing any natural light from entering the space. Classroom desks that usually cover the entirety of the area are temporarily moved to the right corner of the room to make space for the art. Three small, gray tables — typically positioned at the front for a lecturer to use — hold additional artwork.

Within the clutter, professors will deliberate and critique meticulously. Difficult decisions will be made, and some pieces that have taken months to prepare will be rejected. In this brief respite, Lazo and her peers wait nervously.

However, by the end of the afternoon, Lazo has already received her answer. All of her works are accompanied by faculty signatures and were accepted into the show. From here, Lazo will make any adjustments the professors recommend, in addition to preparing the artwork with the gallery’s curator. Most importantly, it is the perfect outcome after months of hard work and preparation.

“Overall I think it was definitely a life-changing experience and I really look forward to seeing how viewers outside of Ceracche react to my work as just a body of work in and of itself,” she said.

For those who attend the gallery, Lazo hopes her self-exploration will provide a deeper meaning for the Mayan traditions, which have often been stereotyped. She has flung herself into the culture and its roles, putting it through her own lens: coming face-to-face with Quetzalcoatl, competing as a ball player, summoning a god through a self-sacrifice and becoming a feared warrior.

With her artwork, Lazo has captured fragments in time.

“Having myself depicted through these different things and not being afraid to show something that was a little bit more grotesque, and eliciting that type of reaction from someone is my main goal, to show that not everything was as pretty as people see through the media,” she said. “There was war, there was sacrifice, and there was this ancient belief in these gods that they worshipped very much to the point that they were willing to sacrifice themselves for it.”

[acf field=”code1″]