Adam Crown, M.A. ’91, in all his frustration, is walking a cup of tea to the table. It’s a hideously cold, -9 degree January morning, and his home is lit, eerily, with the white glow of sun bouncing off snow. Stuck to his refrigerator, among the many magnets and pictures, a photo of a dancer hangs, the woman gracefully arched in some seemingly impossible feat of flexibility.

He puts his cup down on a placemat, white wisps of steam curling over its rim. He sits down at the head of the table and begins confessing.

“I may be the one who is to blame for coining the term ‘classical fencing,’” he says, looking down toward his knees with visible, comical anguish. “It was a stupid thing to do.”

Crown, with his pointed, razor-sharp mustache, is smiling wryly despite his obvious regret. His Ithaca-based fencing academy, the Crown Academy of the Sword, is offering training in “classical fencing,” something he sees as a forgotten art — one forgotten by years of deterioration in the craft. For someone with such a fondness for fencing — for a fencing master, a maitre d’armes — Crown is almost comically upset with the state of it all. He says the recklessly stylized realm of sport fencing, with all its ballet-style jumps and leaps, has departed from the practice’s 19th century roots and spoiled much for him.

“Once upon a time, there was no such thing [as classical fencing,] there was just fencing,” he says. “Fencing was about maintaining a high degree, or very similar, to what you’re doing in actual combat … Over a period of time, the sport of fencing began to diverge more and more and more from, you know, swordplay.”

[block] He says the recklessly stylized realm of sport fencing, with all its ballet-style jumps and leaps, has departed from the practice’s 19th century roots and spoiled much for him. [/block]

He leans in toward the table, as if fearfully telling a secret. Crown is an emphatic, boisterous presence when he gets going on something, especially when it comes to the state of his beloved craft.

“Some of the things that are done in fencing now, in the sport of fencing now, were done when I first started, except when we saw people do those things, we referred to that as ‘shitty fencing,’” he says, smiling.

As Crown vents his peeves, Linda Wyatt, the academy’s only other instructor and a master herself, is sitting at the table, watching along and smiling knowingly as he speaks. The mustached master is not alone is his frustrations, and Linda is quick to add to this rant.

“Most people who find out about us, most people who sign up for classes and most people who hear the word ‘fencing,’ have ideas in their head that come from nowhere,” she says. “This isn’t something that is in the common knowledge anymore.”

Linda is the instructor of Introduction to Fencing — an accelerated, 10-week venture into foils, masks, stance and discipline. She, her hair pulled back into a ponytail, as it will always be, said these 10 weeks will crumble any stranger’s previous expectations of fencing. I’m that stranger.

She turns to me, and I stare back through the fog rising from my cup. Just a few minutes before, I revealed my intention: to get to know this microcosm of swordplay, nestled in upstate New York. I had known, however, since I sat down that these two weren’t letting me off easy — I’d have to learn.

“One of the things that will be most valuable to you, in understanding what we’re doing, is to take a series of classes,” she says. “Because then you will be able to see for yourself what it looks like it’s going to be, and what it ends up being.”

Feb. 8

It’s the first class. Outside, fat flakes of snow sail quietly toward the grounds surrounding the Ithaca Youth Bureau, a cubic, gray building hanging off the edge of Cayuga Lake. Inside, in a large gymnasium, Linda is standing up front on the half-court line. She lifts a silver, glinting blade in front of her.

“This is the latest incarnation of the rapier, called a small sword,” Linda says, holding the handle of the sword and laying the blade across her hand. “Because, it is small.”

She says this with obvious sass — her signature, matter-of-fact tone, all while she scans the room with an exaggerated, raised eyebrow.

The group can’t help but laugh, and so a flurry of giggles fills the room. I’m sitting on a white sideline that traces the edge of a gymnasium within the Bureau, watching Linda with at least 15 soon-to-be swordplayers.

Extremely young, soon-to-be swordplayers.

The little girl next to me — a perpetually smiling, pink-shirted thing, who, for the entire first lesson, weeble-wobbled back and forth — couldn’t have been older than 4. Her shoe, next to mine, looks practically microscopic. In fact, many of the shoes look practically miniature next to mine. As a 21-year-old bearded man, I feel spectacularly, hilariously old.

Though I suppose being placed among these youthful swordplayers made sense. Apart from the instructors, no one in the room could be considered familiar with the sword. We’ve never dueled, parried or fought, and I, for one, hadn’t even held a sheath. When it came to swordplay, we were all the same age.

Linda stands in the center of the room in the icy glow of the fluorescent lights, her hair still ponytailed, but now wearing a jet black, many-buttoned fencing jacket. Behind her, standing by a row of swords, wearing a white crew neck and gray sweats, Tim Wyatt, her son, has his hands clasped palm to palm at his waist.

“I never make a rule I don’t mean,” Linda says to the class. She’s more serious now.

This is the introduction. It’s the start of an essential aspect of this class: making rules. Pairing children, or beginners for that matter, with swords comes with apparent risks. As instructor, Linda knows this and spares no time cutting the risk out of the equation. She delivers her guidelines with power — with heaviness and reason and force, and for that moment, I dared not make a peep. No one shuffled.

It becomes clear, quickly: Linda takes this very, very seriously.

“I just told them,” she said afterward. “I never make a rule I don’t need. I never make a rule I don’t enforce. They break a rule, and I don’t enforce it? Trust is completely gone. If they don’t trust me, they won’t do what I say. And if they don’t do what I say, I can’t put a sword in their hand.”

[block] It becomes clear, quickly: Linda takes this very, very seriously. [/block]

But it is not all grim. Far from it. Safety, for this first class, is paired with humor, obvious as Linda jokingly grasps a sword and pretends to cut Tim in half — then, laughter. Tim, still the sum of his parts, smiles mildly.

We will not see the swords for some weeks after this. They will be bundled up and thrown in the back of Linda and Tim’s cherry-red wagon until it’s time for them to reappear. Much must come first. Footwork. Stance. Rules. But the swords are still, in some way, there. A tension. An anticipation, regardless of whether they are present or not — the concept of them, Linda said, is what makes them.

“What people like at first is swords,” she said. “Swords are cool … But the thing about that, that is interesting, is why? Why are swords cool? And that’s the part that is not so obvious to people at the beginning, that they start to pick up on. Swords are cool because they are powerful, powerful symbols … they’re a symbol of justice, a symbol of strength. A symbol of strength used for good.”

Feb. 15

Standing in first position is, appropriately, the first thing Linda teaches the class, and by even the second session, it has become reflexive. First position is to fencing as idle is to a car: Heel to heel, each foot perpendicular to the other, the students stand along the sideline, their hands at their sides, looking more like the Queen’s Guards than starting swordsmen.

The classes have already begun to get more physical, each class beginning with a warmup — a medley of jumping jacks, stretches and crunches led by Tim. Today, this moment of aerobics is followed up with some starting footwork. So begins the trial of getting our feet under control.

Linda had cautioned the class early on: Learning where our feet like to go, rather than where they should go, is something that would be difficult, and her premonition was spot on. I’m unbalanced, weak, and my en garde stance is shaky at best. I turned my head to spy down the line, hoping to spot other shaky participants, of which there are a few — legs trembling, eyes glancing down toward their feet, shaky hands hanging in the air, imagining a sword. The line, in these moments, vibrates with quiet activity. No one makes a ruckus. All they do is try, and they don’t look so bad.

Halfway through the lesson, my legs are tired, and I’m admittedly a bit sweatier than I had expected to be. Not that I’m alone in this: Fencing, even at this elementary level, isn’t easy, and the room-wide panting lets me know I’m not the only one here sweating away this Sunday morning. I remember something Linda told me before the first class.

“Fencing won’t get you in shape,” she said. “But it will make you wish you were.”

This is certainly true. The exertion of the craft is rooted in endurance. Holding en garde stance, for instance, is like a squat in suspended motion — knees bent, back straight, staring straight ahead, with one arm outstretched at chest-level, as if holding a blade. This alone can get painful.

“Down on your legs,” Linda says. It becomes a sort of catch phrase of hers. “Bend those knees. Butt tucked in, shoulders back, chest out, head up.”

Then, a pause. She stares. She scans.

“Beautiful, keep going.”

Once thrusts, lunges, advances and retreats make their way into the mix, fencing becomes a full-scale assault on the legs, core and forearms. But that’s not today. Today, the class is lined up, arms pointed, looking Zorro-esque despite lacking its swords.

Eventually, we rest. I take a seat on the line, down at the very end by a slim but towering window. I’m one of two lefties in the class, the other one being Josiah Carpenter, who will end up my neighbor in swordplay throughout the class. At 8-years-old, he’s one of the youngest participants in the room, and his shoes — comic book–themed slip-ons — could practically fit in my sweatpants pocket. He is a quiet sort, with a shallow, quasi-mohawk, and while we don’t talk much, I like to imagine we both “get” each other, thanks to our southpaw designations.

However, I’m inclined to stop reading the comic strip on my neighbor’s shoes, as Linda calls the class to attention.

“Today, we’re going to talk about chivalry,” she says. “Chivalry is the moral code of the knight, and it has four parts. Today we’ll talk about the first one.”

“Excellence,” she says, while pacing the gym. Excellence is the first tenet.

“That means everything you do — everything you do — you do to the best of your ability. You try to be excellent at everything you do. No matter what it is.”

[block] Today, the class is lined up, arms pointed, looking Zorro-esque despite lacking its swords. [/block]

The Etude

The snow behind Crown’s house has melted since the winter, and in the March sun, Sancho, his dog, is barking out into the yard, toward the back, where Crown has crafted his own sanctuary of swordplay: the salle d’armes. For those that exhibit skill beyond the Youth Bureau’s intro class, this space — a long, mirrored studio — is where everything, be it lunges or thrusts, will be perfected.

On this Saturday morning, a drum, loud and booming, sounds out inside the salle. One. Two. One. Two.

As a sailing, classical guitar bursts in from the silence, five foils shoot up toward the ceiling. This is the start of an etude, the fencing equivalent to a scale on the piano — run-throughs, made specifically to test the body behind the sword. Raising the sword like so is the “reverance:” a payment of respect. It’s done at the start of bouts, the beginning of classes and, most importantly, to open up an etude. From there, they go through the motions: en garde, advances, retreats, thrusts, lunges.

In the Youth Bureau, these practice runs are done in silence, as they are still being learned. In the salle, however, etudes are joined by music — rhythmic pieces that lead the participants through their motions, up until the final, explosive note: the cri du fer — cry of the blade. It’s a final, impassioned lunge, paired with an equally impassioned scream.

“Et-LA!” Every time, it shakes the room.

Crown is watching the five students from the corner, his arms crossed, his mustache still looking as lethally sharp as always. He, now wearing a black leather fencing guard across his chest, is a far cry from the man ranting over tea.

“That one’s difficult,” he says to Linda, who stands by the CD player. An etude had just finished. “Remember that one.”

In the salle, it’s different. The basics have been nailed down, the foundation laid. Here, they can handle the difficulty — in fact, with the watchful eyes of both Linda and Crown present, where everything can be fine-tuned, the masters welcome it. Not that the students mind, however. Colin Clary was present that Saturday morning and has been fencing with the Crown Academy since he was 8 years old. The now 17-year-old said overcoming an obstacle while training is where the core of his gratification comes from.

“I think it’s pretty satisfying when you work on something and refine it,” Clary said. “And you can tell when you get it right.”

He’s smiling, just thinking about it.

“You go ‘Oh, my god, I got that right.’”

Honor

Nicole Avery reckons it was “The Princess Bride” that got her son, Calum, interested in swordplay, and considering that he once went as Inigo Montoya for Halloween, it’s hard to argue with her.

“He just loves playing with swords, and so we were like, ‘I need to figure out how to do it safely,’” she said. “So we took the introductory class together and both just fell in love with it.”

That was the start for Calum, who has now been fencing for three years. Each Saturday, he joins the few in the salle to work with Crown and Linda one-on-one. The etudes. The lunging. The exotic music.

But it’s not these things that keep him working. For the both of them, mother and son, Nicole said the draw is beyond simple swordplay — it’s the social aspects: the camaraderie rooted in honor and honesty.

“There is a code of honor that goes along with it,” she said. “Always being honest. We’re always trying to help one another. If you’re in the salle and somebody makes a mistake, nobody laughs. It’s all very supportive. You’re all there trying to learn the same thing and try and become the best person you can possibly be.”

“You’re all there trying to learn the same thing and try and become the best person you can possibly be.” [citation] — Nicole Avery [/citation]

Feb. 22

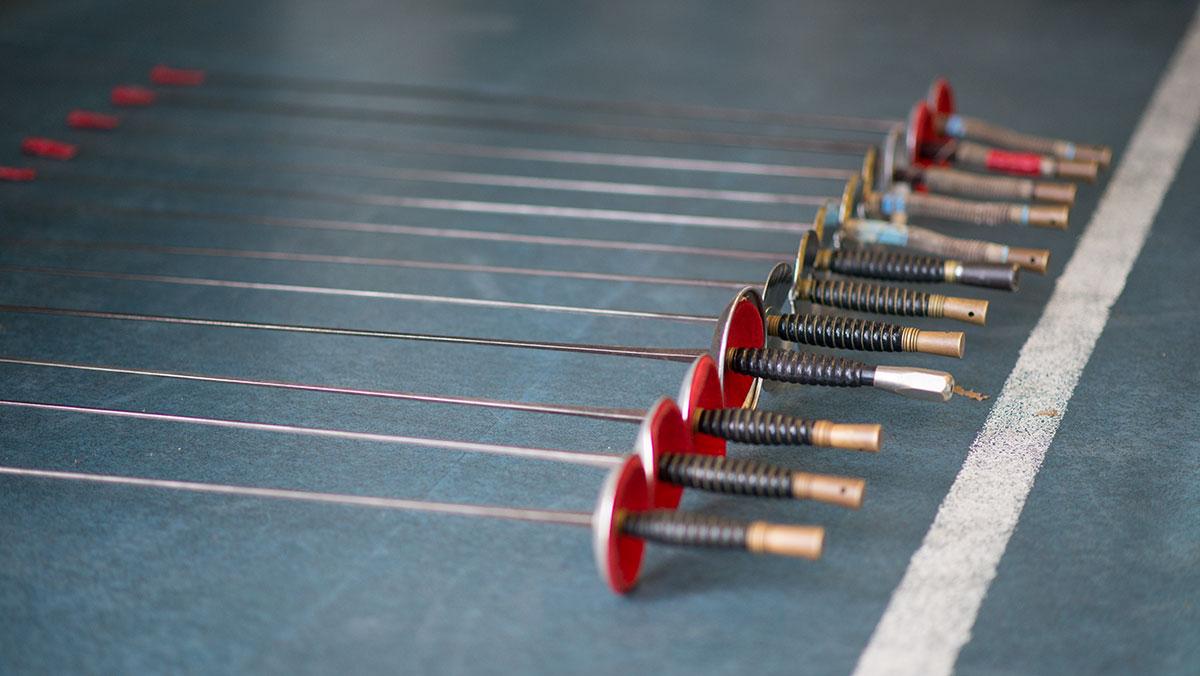

This is the most dangerous part of the class. I’m back on the line in the gym, and the foils are back, pushed to the back corner of the room and lined up in a tidy row. Linda had foreshadowed this last week.

“If you all practice, and everyone looks good, at the end of class next week, we may be able to introduce the swords,” she said. “Just a little bit. You get like, just a little sniff of a sword.”

There was the sniff. A whole noseful. And despite the many gazes, mine included, leaping across the gym toward the swords, we weren’t going to get to touch anything just yet.

“Before I put a sword in your hand, we’re going to talk about another rule,” she says. “This one is the most important one to have. This is called the first rule of fencing safety, and it goes like this.”

She takes a long pause.

“Never point a sword at someone who is not wearing a mask. Not for a second. Not to show them something. Not ‘I’m kidding.’ Not ‘I forgot.’ If you point a sword at someone who is not wearing a mask in this class, you will be immediately removed from the class and not allowed to return. It’s that important.”

And then, in a flash, the swords are in our hands — we have taken arms, as it is called, and I’m holding the weighty hilt at my hip. It’s the only part that feels like it weighs a thing, the blade looking, and feeling, almost hair-thin. They’re flexible, these blades — bouncy, almost like springs. On my sword, I can see where its country of origin would have once been written, the letters now worn unreadable.

All we do is look. At the hilt. The guard. The blade. Today, the swords are new, but they soon become part of every session, and not once is a sword ever pointed recklessly. No one is ever removed, no one is scolded.

“[The first day with swords] always goes exactly like that,” Linda said to me as the students emptied out of the room. “It is not an accident. The entire three classes up to this point are to lead to that, so that I know that they will do what I ask them to do, when I ask them to do it. You have to set it up from the first minutes.”

The students will, without fail, remain true to that rule.

March 1

“We’re going to talk about chivalry again,” Linda says. The class is resting after the opening footwork, and from where I am sitting I can spy the swords laid out neatly, as always.

“The second tenet is truthfulness,” Linda continues. “Which sounds really simple: Tell the truth. Who here thinks people tell the truth all the time?”

I look around expecting hands to shoot up all the way down the line. Maybe I expected this because they’re young. No hands go up.

“Who here thinks anybody tells the truth all the time?”

Still no hands.

“Who here thinks there are people who at least try to tell the truth all the time?”

The hands shoot up. Mine shoots up. There is hope.

“Here’s what I want you to do,” she says. So begins a new “hero homework” assignment. Linda had given a few of these throughout the class, their tasks demanding niceness, integrity and honesty — a sort of take-home test for chivalry. Just a few classes before, the assignment was to smile at others. Today, it’s about truth.

“I want you to go out and tell the truth. But I want you to tell the truth in such a way that it builds people up. … Find good things to say about people that are the truth. Don’t make things up, don’t exaggerate, but tell them things about them that you like, that are true. See what you come up with.”

March 15

We’re getting better at this. You can hear it in the steps. They’re cohesive. Together. Each lunge sounds less like a storm of footsteps and more like a grand, many-legged stomp, and while some students have stopped showing up — the wobbly, pink-shirted tot being one of them — the class feels as focused as ever.

The sessions were getting harder, too: Warmups had become workouts, and the footwork had become work for the feet. Thrusts were held longer, despite shaky forearms, and coming en garde was a split-second decision. Each cri du fer was strong, impassioned and satisfying. I looked down the line, and what was once a handful of starting swordsmen was now an upright, silent line of knights in the Youth Bureau.

But this session is over, and we have just a few minutes left: enough time for the third tenet.

“The one I want to talk about this week is loyalty,” Linda says. “Loyalty to whatever you give your word to be loyal to … What this is about now is keeping your word. Keeping your word.”

I’m looking down the line, at those who had stayed up until this point.

“When you make a promise, you keep it,” she says. “Your word is one of the most valuable things that you have. Nobody can take that away from you, only you can take that away from yourself.”

The Journey

Back in January, my tea bag is floating, like a buoy, against the foggy edge of my mug.

“The question is not what you learn of the sword, necessarily, but what you learn by learning the sword,” Crown says to me.

I mention that the concept reminds me of the old, often cliche saying: It’s not the destination, it’s the journey.

Hearing this, Linda looks my way.

“It is,” she says. “It’s both.”

April 12

It’s the last class, and, just a few seconds ago, Linda stole the air out of the room with a single sentence.

“Here’s what we’re going to do,” she said. “I’m going to give you all the opportunity to do the etude by yourself.”

The line stays quiet, apart from a few small gasps. A few nervous snickers and glances at the floor. All of these, and some anxious shuffles, like the collective pulse of the room has climbed a few beats per minute.

“This is not a test,” she continued. “This is an opportunity to see what you do know and what you don’t know.”

The trial had started with me. Just a few moments ago, I had stepped up front and acted out the motions: reverance, en garde, advance, retreat, thrust, lunge and of course, cri du fer. I had done it a hundred times before, and yet I shook as I held en garde stance.

Could it have been fatigue? Yes, I suppose it could have, but that would be a lie.

What quickly becomes clear, is this: pulling off a lunge — stretching out, leaning and holding that stance — or yelling a cri du fer with real power, all without the safety of a group, is a true experience in anxiety. It’s the same etude as always — the class had done it so often, it seemed trivial when stuck to the white line. But at the front of the class, it felt different.

And now, Josiah is standing, sword in hand, in front of the class. The entire class.

“Lecon premiere,” he says, in quiet, chirping French.

“Allez,” Linda says. That means go.

He extends his arm, draws his sword and raises the foil, which turns invisible in the light of some merciful afternoon sun, toward the ceiling in respect.

He moves to en garde. He advances, he retreats and he takes his time. Then, thrusts. One lunge, then the second. All that’s left is the cri du fer. He lunges forward.

“Et-la,” he says, softly. It’s feathery, and barely echoes off the walls of gym, but it still counts.

Just like that, Josiah has made it. I give him a thumbs up as he sits down. He’s not the only one to succeed. They all do. Each of the students — some louder and more confident, some absolutely terrified — all do the etude. And despite any mistakes, any skipped advances or a shaky lunge, they applaud one another afterward. Then, Linda delivers her advice.

“Relax your shoulders.”

“Your focus is wonderful.”

“Get big, get large, take a long stance.”

It goes down the line, etude after etude. A dainty cri du fer, then a louder one. Long lunges, then short ones. Everyone is different, and everyone has problems, but everyone has learned.

“By god,” I think to myself, watching each one of them. “They actually know it.”

I look to Linda, expecting her to be wide-eyed, but she’s placid, unsurprised. She’s simply leaning against the wall, like always, her hair ponytailed, watching and smiling knowingly.

She stays like this until every last lunge is executed, and every last thrust, thrusted. As the last student returns to the line, Linda takes her place at the front once again. She scans the room.

“First thing that I’d like everybody to do is give yourselves a big hand,” she says, to a smattering of applause. “Because contrary to what some people may have believed, none of you died. All of you managed it.”

We stand down arms. The class is coming to an end.

“This is one of my favorite, favorite classes because I get to see how everyone is doing and I get to tell you how well you’re doing,” Linda starts. “We’ve talked about chivalry throughout these classes. We’ve talked about excellence. We’ve talked about truthfulness. We’ve talked about loyalty. And today I want to talk about the fourth tenet of chivalry, which is my favorite one. It kind of puts everything else together, and that is benevolence.”

A gaggle of parents have arrived, and they’re lounging outside in the Youth Bureau Lobby. But Linda continues.

“Most people in the world will do good things, will do the right things, if it is easy,” she says. “Most people will do the right thing if it doesn’t cost them too much. If it’s convenient. Some people will do the right thing, stand up for the truth, do something good, even if it’s not easy. Even if it’s difficult. This is what the job of a knight was. It’s somebody that goes out into the world and actively looks for opportunities to do good things.”

Linda lifts a fencing mask off the floor and tucks it under her arm. In it, shining brightly under the lights of the gym, are miniature 3 Musketeers bars.

“That is our last hero homework assignment, is to become that kind of person,” she says. “A person who goes out into the world and looks for chances to do something good. Let’s see how many of those you can find.”

She walks down the line and gives out the sweets. She thanks every one of us. As the gym empties out, I look toward the back of the room: The foils, laying in the same place they were on the very first day, are bathed in the sun, and look brighter than they ever did before.