How much a person understands about race correlates with how much a person actually thinks about race. For most white people living in the U.S. — arguably the group that thinks about it the least — their understanding of race is little to none.

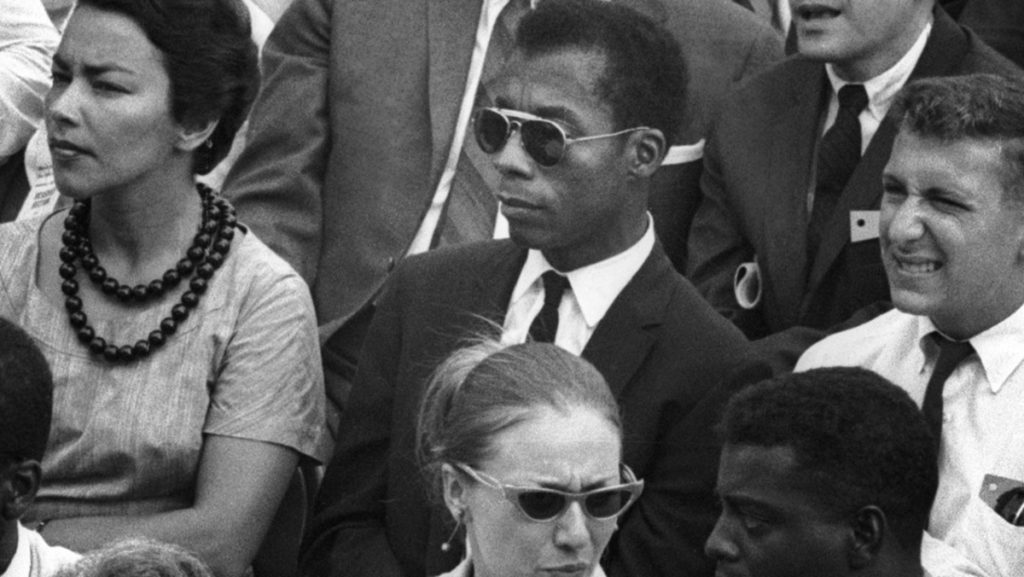

The understanding and relationship to race are the fundamental premises of the documentary, “I Am Not Your Negro.” The documentary was written by prolific African–American writer James Baldwin and was nominated for an Oscar for best documentary. The source material for “I Am Not Your Negro” comes from a set of unpublished letters Baldwin had written before his death for a book called “Remember This House.”

The project was to be a critique of race in America through the life, death and work of three prominent black activists: Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and Medgar Evers. The documentary uses Baldwin’s writings, the lives of three prolific black activists, clips from old Hollywood films and stills from history to produce a nuanced and searing critique of race relations in America.

The strongest element of the film is Baldwin’s presence. Though the prolific writer died 30 years ago, the use of his texts, writings and even interview clips turns Baldwin into his own prescient character in the film. Director Raoul Peck made a wise decision in building the documentary around Baldwin instead of building Baldwin around the documentary. In this way, Baldwin becomes the driving force of the film from start to finish. It is evident that, from the beginning, the film was about Baldwin and his ideas rather than the idea of race relations itself.

The texts that were picked from Baldwin’s collection do more than merely expose the audience to uncomfortable, sorely needed truths about race in the United States; they go a step further in making the audience truly think about the issue. The unapologetic nature of Baldwin’s words in particular influence white audience members to reconcile with their own morality and blindness to the operations of race and systemic oppression. It is their blindness and immaturity, Baldwin says, that causes and fuels the destruction of black and brown bodies. It has created an illusion of progress and equality, one that has only exacerbated the oppression of black people even further.

The documentary expertly uses a slew of films featuring black and white actors to comment on the relationship between the oppressed and the oppressor. Many film clips portray a respectful friendship between a white character and a black character. Their relationship is cordial, with not much said about the power dynamics that exist between their racial identities. But the film juxtaposes these friendly interracial relationships with the reality of race relations in the U.S. This focus on race in popular culture forces white viewers to realize that films can operate as a medium of denial and a way to convince white people that relations with people of color are cordial, respectful. They are part of a greater scheme to induce white people into believing that they have no responsibility in mending race relations. The documentary points out that this only influences white people to believe that race is no longer a problem in a way that blinds them to the very stake they have in white supremacy and oppression.

“I Am Not Your Negro” draws many of its visuals from history, many of which show graphic beatings of black people at the hands of white people, giving the film a brutally honest and gritty tone. These clips stretch from the mid-1900s up to the 21st century, when hundreds of black men and women became victims of police violence. The graphicness of these images forces the viewer to truly reckon with the physical and psychological violence waged against black people for centuries. Juxtaposed to the narration of Baldwin’s work, the images bring the writer’s message to the present. These images makes audiences wonder why this violence has happened and when it will stop.

This is where Baldwin provides a potential answer: The violence will not stop until the white population wakes up from its perfect dream and acknowledges the carnage lying at its feet. It is clear throughout the documentary, from the narration of Baldwin’s texts to his interview clips, that for too long, white people have comforted themselves with blindfolds to avoid the truth of their stake in white supremacy — engaging in what Baldwin calls “moral apathy.” It has led to the creation of a white American innocence that juxtaposes itself to the stereotype of black criminality and incivility. And although Baldwin died in 1987, the release of this film in 2017 effectively transposes his ideas into the present, conveying the insidious cycle of denial and immaturity that repeats itself time and time again.

“I Am Not Your Negro” presents a poignant and powerful analysis of race relations in this country that goes unmatched by any other film. The documentary leaves viewers grappling with their complicity in racial power structures. “I Am Not Your Negro” creates a discomfort that is sorely needed if the United States ever wants to understand race. Baldwin’s words make the audience ponder the fundamental question: Why do we have race, and why do we need it? The documentary asks its white viewers to wake up and answer this question for themselves.