Standing at the front entrance to the Campus Center at Ithaca College on move-in day, in August 2013, Mohamed Shaw was far from home. He could overhear other new students and their families talking about the private schools they attended or how accomplished their parents were, while he thought of the countless times he had walked through a metal detector to enter his Brooklyn public school. They spoke in ways he understood but didn’t speak with his family or friends. And, most noticeably, he stood out among a sea of white.

What did I get myself into?

“You gon’ be OK?” his mother asked.

“We gon’ see, Ma.”

Getting in

Shaw’s high school had basic textbooks and a few sports, but after-school programs were cut. There’s a gun shop across the street from the school, and there was some gang violence. Fast–food restaurants line the avenue. His father is a construction worker, his mother unemployed.

If it weren’t for a certain teacher and an influential principal, he might not have considered a private institution like Ithaca College.

Colleges are faced with a conundrum: how to enroll an academically competitive class while meeting students’ financial needs and balancing the institution’s budget in a country with inflated costs of higher education with relatively little public support. A college’s reputation is measured, often, by how many students it turns away.

Students from low-income backgrounds historically have had difficulties fitting into this equation, excluded first by the ballooning costs of college and then by cultural differences between them and their middle- or upper-class peers.

But even before tuition costs become a concern, it takes considerable time and money to apply to schools and to take standardized tests — both processes that affect chances of acceptance and receiving scholarships. A 2015 U.S. News & World Report survey found that the average cost of a college application is just over $40, but the most common fee charged among the colleges surveyed in 2015 was $50. Some colleges waive this fee for students who apply online, should they have easy access to do so. The College Board suggests students apply to five to eight institutions. With the writing portions included, it costs $57 to register for the SAT and $58.50 to register for the ACT.

Dongbin Kim, associate professor in the Department of Educational Administration at Michigan State University, said the likelihood of a student’s making the effort to undertake this process — and make tough decisions about diverting financial resources to it — is affected by the de facto tracking system that pervades all levels of education in the United States. One has to be better prepared in elementary school to get into advanced math classes in middle school, and better prepared in middle school to be in the honors courses in high school, where attention and resources are most often diverted. Some families, she said, believe college is automatically out of reach since they look at how the news media focus on soaring costs, leading them perhaps not to focus as much on studying and preparing for that path.

In Europe, students are tracked at much younger ages into certain paths of higher education, determined by standardized tests during or before high school. Postsecondary education is free in many European countries, and there is a much tighter correlation between education credentials and occupation, as David Karen said in the journal Sociology of Education.

But because of that tracking system, Kim said, there is a smaller number of students who are siphoned into the college path in Europe. The percentage of postsecondary enrollment in European countries — 64 percent in France, 65 percent in Germany — are significantly lower than that of the U.S., which is 87 percent, according to the World Bank. Thus, finances are less of an issue for individuals — taxes are significantly higher in Europe, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. But this system could exacerbate inequality in society, Kim said.

“Once you’re in a track, you’re stuck there,” she said.

From the policy level, then, the system in the U.S. appears more open and equitable, but as Karen writes, the U.S. system’s “client power” tends to give greater advantage to the already privileged.

The difference comes down to how the public treats higher education: whether it should be a public good, in which the benefit goes to everybody, or a private good, in which the benefit goes to only those who buy into it. Here, Kim said, in practice, the latter applies.

“In Europe, the general public still believe higher education is a public good,” Kim said. “If higher education is a public good, the general public should pay a portion of it. In the U.S., we don’t believe higher education is a public good.”

Jamey Rorison, director of research and policy at the Institute for Higher Education Policy, said the IHEP believes it’s a myth that students from low-income backgrounds are always less academically prepared or less likely to succeed in college, and that this assumption feeds into these students’ disadvantage.

“We think it’s really important — viewing this through an equity lens — we need students from low-income families to be served by the best colleges and universities,” he said. “If we continue to usher them into less selective institutions, that’s going to potentially harm their chances.”

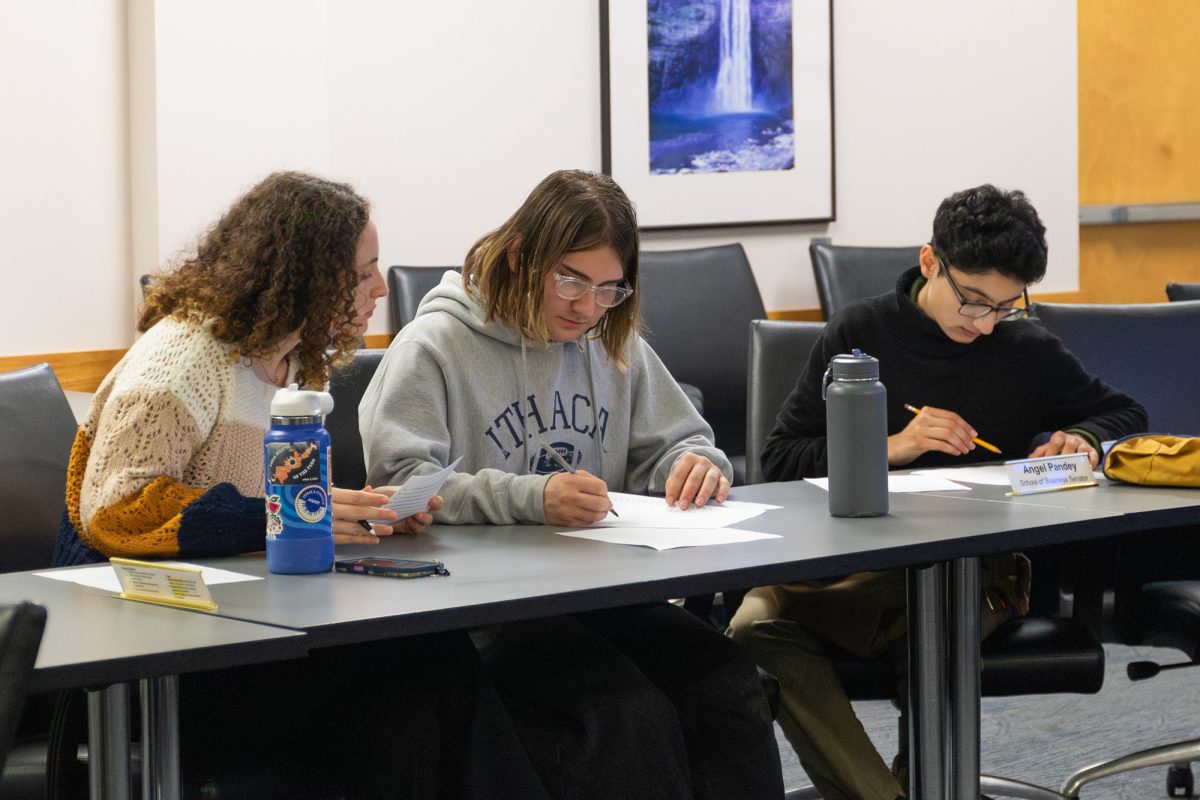

Brooklyn-raised senior Omar Stoute, for example, helped found The First Generation Organization, a student club for first-generation students to gather and discuss their experiences. Shaw said he plans to go to law school and become a civil rights lawyer.

Shaw carried his experience in high school on his shoulders through his first and second year of college.

“Going through that public school system makes you question yourself,” he said. “[Going to college] was a feat, but a lot of pressure to make it, for other people of your background.”

Paying for it

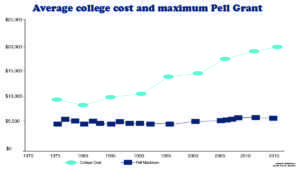

Affordability, Rorison said, is a two-pronged problem: insufficient financial aid and soaring college costs. He said there should be a shared responsibility among all levels of policymakers to aid in improving affordability, most notably through increasing Pell Grant caps and the number of recipients. Pell Grants are federal grants targeted at students from low-income backgrounds.

Pell Grants could previously cover over half of a student’s education, but over the past three decades, their purchasing power has sharply declined, Rorison said.

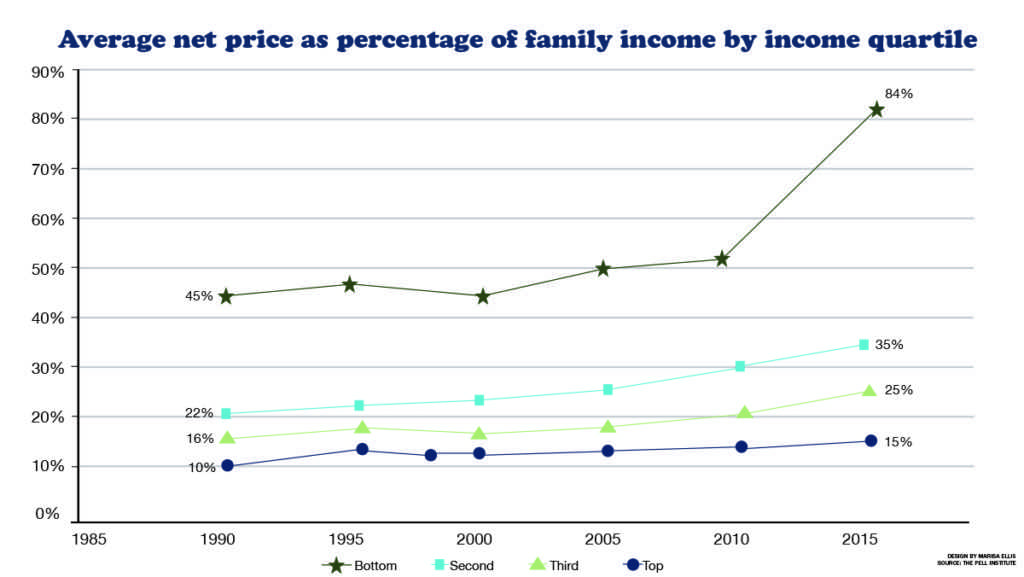

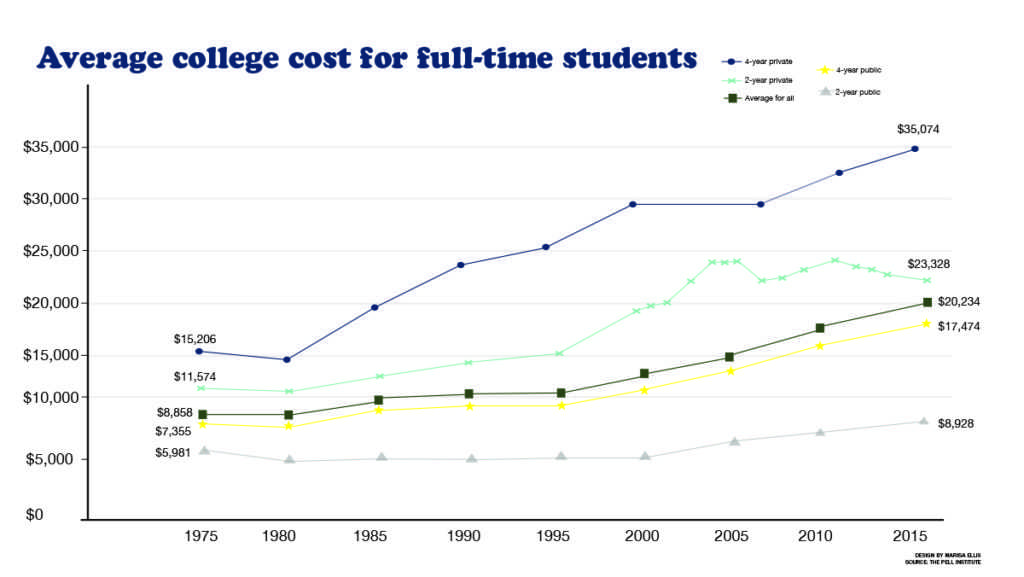

Indeed, the percentage of college costs covered by Pell Grants has decreased from 67 percent in 1975–76 to 27 percent in 2012, according to the Pell Institute’s “Indicators of Higher Education Equity in the United States” 2016 report. In constant Consumer Price Index dollars, the maximum grant only increased by less than $1,000, or an 18 percent increase compared to average costs of college, which increased by 128 percent.

Cutting Pell Grants — which the Trump administration has proposed doing — would seriously disadvantage private colleges in recruiting low-income students, said Stella Flores, associate professor of higher education at New York University.

“If students don’t have additional funds, they’re going to end up working,” she said. “There’s no way to pay for tuition on 20 hours of work.”

In constant Consumer Price Index dollars, average college costs were 2.3 times higher in 2012–13 than in 1974–75, according to the “Indicators” report.

As it is right now, low-income students find out too late how much they will have to pay for college, she said, and every college varies widely with little predictability.

Tom Mortenson, a senior scholar at the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education said he believes wealthy students should be expected to pay most or all of the cost of higher education. Right now, politicians feel the pressure to keep tuition low enough for wealthy people because that’s whom they most hear from, he said.

In the past two decades, more undergraduates have received financial aid in general across all institution types, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. But this aid tends to benefit students disproportionately to their need, revealing inequitable patterns and impediments to access for low-income students.

The New York State Arthur O. Eve Higher Education Opportunity Program at Ithaca College provides grants and academic support for about 60 students from low-income backgrounds each year, like sophomore Woizero Jarvis — who, as one of six children with a single mother, wondered how she would pay for any school — and Stoute, the son of a schoolteacher and a retired nurse, who is on food stamps and works in the college’s Office of State Grants.

Of students at the college who were awarded any need-based aid, on average, 90.4 percent of their need was met through financial aid, according to the 2016–17 Common Data Set. Of the 1,138 freshmen in Fall 2016 who were awarded any financial aid, 632 had their need fully met, based on the need determined by the FAFSA.

For sophomore Jonelle Orsaio, from a suburb of Utica, New York, college would have been impossible were it not for having most of her tuition covered.

“I looked at the price and said, ‘Absolutely not,’” she said.

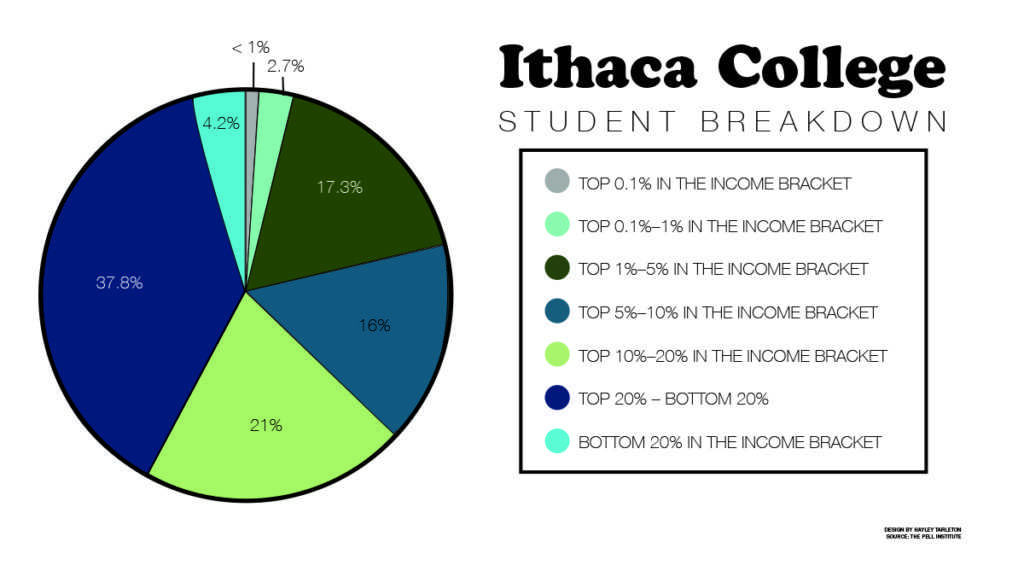

But only 4.2 percent of the college’s population is from the bottom 20 percent of the income bracket, compared to 58 percent coming from the top 20 percent, according to data from The Equality of Opportunity Project and compiled by The New York Times. The study caps the 20th percentile at an annual family income of $25,000, and the top 20 percent has an income above $111,000.

Gerard Turbide, vice president for enrollment management at the college, said 20 percent of the student body is eligible for Pell grants — a federal need-based grant for which students with family incomes less than $50,000 can qualify — 14 percent are first-generation students, and 86 percent attended public schools. However, 92 percent of the college’s revenue comes from student tuition, creating a demand for students who can pay.

Overall, the growth of merit-based aid has outgrown that of need-based aid, and at the same time, students of high-income backgrounds have benefited more from merit-based aid than students of low-income backgrounds have, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

The percentages of undergraduates receiving both need-based and merit-based institutional aid has increased from 1999 to 2012, but merit-based aid increased twice as much — by 10 percent — and benefitted only 3.4 percent of the lowest quartile of income in 2012, whereas need-based benefitted a greater proportion of the lowest quartile: 22.4 percent.

Among all types of institutions, the percentage of students receiving merit aid who were high-income increased from 23 percent in 1995–96 to 28 percent in 2007–08. The percentage who were low-income shrank from 23 percent to 20 percent in those years.

Crystal Coker, a postdoctoral research associate at the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation — a private foundation that awards scholarships to high-achieving, low-income students — said this shift toward merit-based aid can be explained by colleges’ desire to entice higher-achieving students and higher-paying students who can help the institution sustain itself while boosting its profile and ranking.

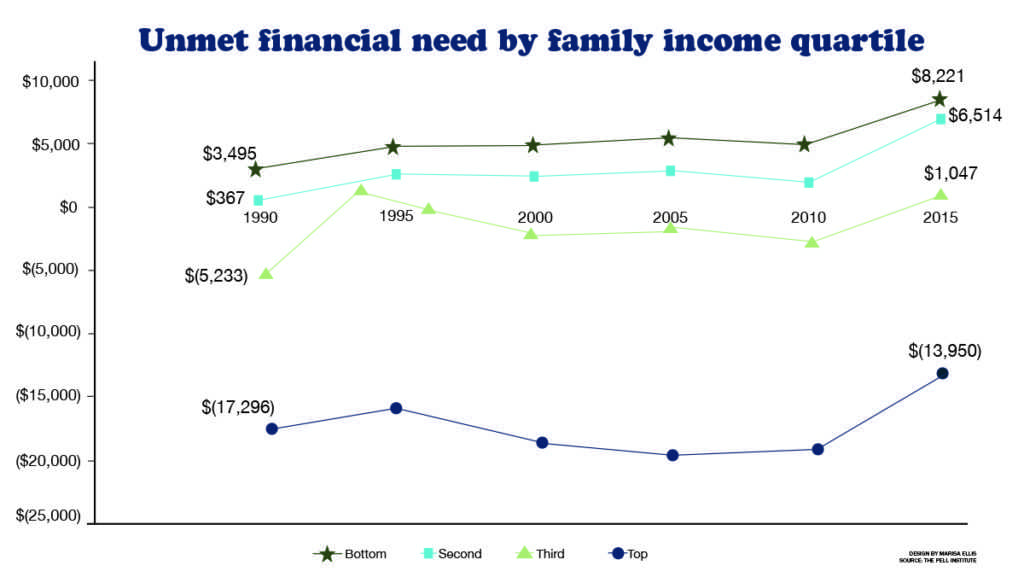

“By awarding merit scholarships, these high-income students are provided with higher than their need, while low-income students still have unmet need,” Coker said.

In 2016–17, Ithaca College awarded about 77.5 percent of its institutional aid budget in the form of need-based aid and about 22.5 percent in the form of non-need-based need, though these numbers are not absolute, and both include some portion of extra non-need-based aid necessary to meet students’ need. Of the 1,630 first-time full-time freshmen in Fall 2016, 70 percent were determined to have financial need, and of those 1,138 students, 97.2 percent received need-based aid and 33.4 percent received non-need-based aid — a significant overlap.

Ivy League schools refuse to give financial aid in the form of merit scholarships to students who don’t have a demonstrated need for them, Mortenson said. These schools can afford to do this, but most schools need to consider the factors Coker highlights more heavily.

“What you end up with is the lowest-income students face enormous financial barriers to higher education, and wealthy students whose Expected Family Contribution exceeds cost of attendance still receive financial aid — that, I don’t see as anything more than a bribe,” Mortenson said.

After financial aid was accounted for, in 2012, families in the bottom quartile were left with more than $8,000 of unmet need on average in paying for one year of college. Families in the top quartile of income were left with a nearly $14,000 surplus, according to the Pell Institute’s “Indicators” report. Unmet need is defined as the amount of financial need that remains after the Expected Family Contribution is calculated and grants are taken out.

The criteria for merit scholarships, Mortenson said, usually combine test scores, high school grades and class rank — all academic measures that are correlated with family income.

A study by the College Board in 2013 documents a strong positive correlation between family income and SAT scores: higher income, higher scores.

It’s a cycle that trickles down from wealthy parents to wealthy children, and so on, said Patricia Albjerg Graham, Charles Warren professor emeritus of the history of American education at Harvard University.

“Children of affluent families are just vastly more likely to be tracked through their school into a curriculum that prepares them for college,” she said.

“Often” and “more likely” are keywords most researchers use because, as Rorison points out, merit scholarship still has need-based components. Merit-based versus need-based is not a complete dichotomy, but it’s true, he said, that merit-based is often not equity-focused.

“We definitely feel that merit-based aid is less effective in achieving equity goals,” he said.

But making sure the process is as equitable as possible for selecting recipients of the Park Scholarship, a full merit-based scholarship for applicants to the Roy H. Park School of Communications at the college, is Park Scholar Director Nicole Koschmann’s goal.

It’s a challenging goal because the goal of the merit scholarship is to attract the best students, but as far as a student’s financial circumstances and family background goes, the selection committee only knows what the student tells them in a cover letter, for example.

Koschmann said her goal is to look at the breadth and growth of an applicant from one point to another, and not to compare students’ differing starting points. Though this analysis can also be influenced by her bias, she said the benefit of a selection committee of 10 people is to have a system of checks and balances on this process.

“My goal is not to penalize students for their circumstances,” she said.

The college is a moderately selective institution, Turbide said. Its financial aid office seeks to reconcile the financial-need gaps of incoming students with the college’s budgetary needs, as well as the desire to fill in balanced academic programs — all in a large balancing act. Much of the merit aid the college awards, he said, is used to fill in the gaps left by need-based grants.

“In an ideal world, we would only offer need-based aid,” Turbide said.

But given the inflated costs, the stakes remain the highest for students of low-income backgrounds. Jarvis said she feels she always has to be on top of her game, perhaps more than some of her peers.

“I can’t afford to fail,” Jarvis said. “I can’t afford to take an F, a C, a W — I can’t afford any of that.”

Staying in school/social cost

Beyond access, success in college is often another hurdle, Flores said. Low-income students are surrounded by a college community populated mostly by students of middle- and upper-class backgrounds. Students from the bottom quartile of the income bracket — less than $35,000 a year, which is the income used in the “Indicators” report — represented 10 percent of bachelor’s degree recipients in 2014. That year, about 33.6 percent of the population had household incomes below that threshold, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“If we don’t improve academic prep and opportunities for students to be prepared in college … then we’re addressing the wrong problem,” Flores said.

It wasn’t until his junior year, Shaw said, that he felt he got into the swing of college. He brought habits with him that did not serve him well his freshman year — issues with punctuality and core critical-thinking skills. He was always a step behind his classmates.

“High school didn’t prepare me for college at all,” he said. “College ripped me to shreds.”

This was also the case for Jarvis, who grew up in the Bronx and attended a small public school on the Lower East Side. No after-school activities, some Advanced Placement courses — the focus was more on fun than academics, she said. High school was a breeze, and it didn’t prepare her for college work.

“Freshman year was hard — I didn’t know how to get through it,” she said. “It still feels like a competition.”

The difficulty of the first year of college is compounded by the pressure of making ends meet, a cycle that persists throughout the educational career of students from low-income backgrounds, Kim said.

“You go to college, but you get loans, and you have to work to make money to survive, and while you are working, you cannot study, and rich students can afford to not work,” she said. “You can’t get a good GPA. … It’s a bad, bad cycle. The poor get poorer; the rich get richer.”

Stoute matriculated through the Beacon School in Manhattan — a public school with 86 percent of students qualifying for free and reduced lunch — and he figured he would end up at a CUNY school due to his financial situation.

He found out about the HEOP program through a guidance counselor and started out in college as a biology major.

But when the professor gave directions in class, listing the names of various tools and equipment, he had to spend extra time figuring out what to grab and where to go. He had never seen the equipment before, whereas most of his peers had been doing those experiments in high school.

“There was a psychological factor there, too, because I’m just like, I’m not as good as the other students here,” he said. “There’s a variety of reasons why someone might be underprepared for school. It doesn’t mean they’re not as smart.”

Part of the access problem is not only financial, but psychological: the obligation to stay close to home or the difficulty to see what might be possible outside of one’s community.

Then there’s an added psychological burden attached to stereotypes of poor people and students, Shaw said.

“‘People should try harder,’ or ‘They don’t deserve certain things’ — We don’t have certain things,” he said.

Outcomes

For Stoute, the pressure didn’t subside after getting into college. He can’t take his post-college plans lightly — he needs a job right away. His father retired recently, leaving Stoute to rely on the college’s health insurance, which he said is inadequate and expensive — so he’s one illness or injury away from being set back.

“I play the don’t-get-sick game,” he said. “Now I don’t want to go to the doctor.”

He might be treated differently for not having money on-hand to socialize when others want him to, and the decision to travel home to New York City for short breaks is one that carries financial weight.

“Some people don’t have the understanding that just because you have money to do something right now, doesn’t mean I have money to do something right now,” he said. “People don’t have the understanding that if they make a mistake, they have a backup. I don’t have a backup. It’s like living your life on the edge, especially when you’re in a college environment. The stakes are always very high.”

There is a growing hypothesis among researchers that there will be a cascading of students from one higher education sector to the other as costs keep increasing at some schools while others push the free-college movement — for example, low-income students will continuously filter themselves into the public sector, and higher-income into the private, further widening class divisions.

However, Flores said that if college is made more affordable, not only will more low-income students attend, but the sheer number of students who graduate from high school may also increase because of the hope for access.

“That promise of affordability helps students move through the pipeline who may have previously been inclined to not go to college,” she said. “I’d like to think that there’s a lot of hope in that movement.”

But Kim said she does not believe public support is heading in that direction — toward considering higher education a public good that should be publicly funded, hence lowering costs and improving access.

“I think it’s going to get worse,” she said.

Should everything stay the same — public support of higher education does not increase, and, therefore, federal and state governments cannot increase funding for it — one way to ameliorate the situation is to make financial aid much simpler, Kim said.

Shaw doesn’t harbor resentment toward others of different socioeconomic status. They have their perspectives, biases and backgrounds, and his mother always taught him not to be jealous of others. It’s easy for him to gauge, though, who in a class is more prepared and who had more access to resources growing up.

“I would hear in class still to this day, students talking about ‘I don’t really know what that’s like; I grew up in a predominantly white neighborhood, blah blah’ — I don’t even get mad anymore, I’ve heard that so many times,” he said. “I understand where you’re coming from. You don’t have to rub it in other people’s faces. We weren’t lucky enough to grow up in the same places you did.”

When he goes back home, he notices more aspects of his neighborhood he hadn’t before: the fast–food restaurants, the gentrification, the fact that the city’s snow plows don’t go to his street.

When he leaves college, he said, he wants to pursue a law degree and become a civil rights attorney to advocate for policy change that will help people’s voices be heard.

“People of low-income, people of color, already suffer enough as it is, so I want to be that [helping] hand,” he said. “We aren’t taught to believe in ourselves as much.”

This is what Jarvis said she wants to do in the future — to teach young people to do this, to give back to HEOP and her family.

“I try to give people the benefit of the doubt — it’s because my lifestyle was way different, and I know what it is to struggle, and I know what it is to not have a support system all the time, but to make a support system for yourself,” she said. “Sometimes you can’t rely on other people. You have to start with yourself. My struggle has shaped my progress.”