In Spring 2017 at Ithaca College, then-freshman Courtney Webster was taking 13 courses, worth 16 credits, to fulfill her music outside field major. The stress and exhaustion from her workload finally became too much while she was onstage performing for her oboe repertoire class.

“My whole body just started shaking,” Webster said. “I just burst into tears.”

She ran off the stage, and her professor followed. Webster said her professor told her that her body and mind had reached their limits. Her experience is not unique as a student in the School of Music.

“It’s very stressful, and it’s very exhausting,” Webster said. “It really drains you as a human, and it kind of takes away the things you enjoy, and you kind of lose what you enjoy a little bit, which is unfortunate.”

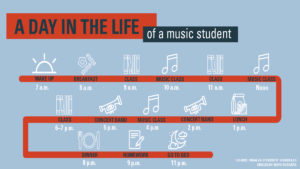

Many students in the School of Music have to take approximately 18 credits every semester, and some often petition to take over the 18–credit limit. The demands of students’ course loads put a strain on their mental health and well-being, as well as on their personal lives outside school. Many students also said that unhealthy competition, excessive criticism and exhaustion are common in the music school’s environment. As a result, students report having no time for activities and courses outside music or for basic self-care, like eating and sleeping properly.

Karl Paulnack, dean of the School of Music, said the number of credits per semester is necessary for students to obtain bachelor’s degrees, adding that any fewer requirements would leave students less prepared for music careers. He also added that the requirements at the college are similar to most other music programs.

The School of Music is the longest–running school at the college because the college was founded by musician William Egbert in 1892 as a music conservatory.

Sophomore Baily Mack, a music performance and education major through a four-and-a-half-year double major program the college offers, is taking 18.5 credits this semester. She said she has never taken fewer than 17 credits per semester.

On most days, Mack rarely makes it back to her Circle Apartment before 9 p.m. After these long days, she typically stays up until 1 a.m. finishing her homework. In between, she has little to no time to eat, exercise, socialize or even properly sleep. To pay the approximately $700 cost of taking an extra half credit, Mack said she works at least 12 hours per week between her two jobs.

Her schedule as a music student has come at the cost of taking care of herself, she said.

“Taking a break can be seen as laziness, especially in such a competitive environment,” she said. “As supportive as the environment is, it’s definitely competitive.”

Paulnack said the school’s staff and faculty struggle to find a line between accommodating students’ needs but also making sure the program prepares students for careers in music.

“If a student doesn’t want to be pushed to their limit and then five years later says, ‘You don’t really prepare me well for the profession,’ those things are in conflict with each other,” Paulnack said. “You have to be able to handle stress. … Life will not grant you that. You will not have flexible attendance when you’re in a job.”

Webster said the rigor of the coursework and the amount of time a student spends in the School of Music can be taxing. “With the course load, you don’t really have the opportunity to take classes that you would necessarily be interested in otherwise, like outside of the music school,” Webster said. “Music is great. I love music, but when you’re living and breathing music 24/7, it becomes very overwhelming.”

A study published in 2017 found that music students, similarly to student–athletes, strive for perfection because of the high expectations surrounding their performances from their teachers and others in their circle.

Liliana Araújo, professor at the Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, who contributed research to the study, said musician culture tends to push forth the idea that someone has to be best, which puts unrealistic pressure on musicians.

“There’s a culture that still focuses a lot on this idea that in order to be a musician you always have to be the best,” Araújo said. “To be in first place, you always have to strive for perfection.”

Sophomore Kerrianne Blum said it is difficult to hear constant criticism of her performance because being a musician is not just a career path but also a major component of her identity.

“You’re judged on doing what you love to do,” Blum said. “For a lot of musicians, it’s something they’ve been doing since they were little.”

The stress Blum felt made her slowly resent pursuing music, stress that made her question her career path, she said. She was previously a vocal performance major, and she now studies communication management and design in the Roy H. Park School of Communications.

Araújo said musicians tend to isolate themselves from their peers because of the internalized competition. This also makes it harder for them to come forward about their struggles and form meaningful bonds.

“There’s still this idea that you can’t really show your weakness because your peers can also be your competitors,” she said. “This culture of competition, constant evaluation, constant pressure to excel still exists.”

Mack said the competition can drive a wedge between friendships.

“The competitiveness can definitely put strains on relationships, like people who get a better part than someone else, and then someone’s salty about it, and then it really affects the dynamics,” Mack said.

Susan Waterbury, professor in the Department of Performance Studies, said students might be taking on too much to allow themselves to learn what they need for their careers. Waterbury maintains an active performance schedule while teaching at the college.

She said colleges are supposed to follow a Carnegie unit for college credit. A Carnegie unit, according to the Carnegie Foundation, is a measure of the time a student has studied a subject. The measurement means a one-credit class in the School of Music should only have three hours of outside work.

“What happens here is that many, many people, including me sometimes, we all — by wanting our students to have better experiences — sometimes accidentally add more than that,” Waterbury said.

Some professors in the music school said they notice when students are struggling, and they attempt to help students outside the classroom. Professors recognize the pressures and high expectations put on their students, they said. The School of Music brings a counselor from the Center for Counseling, Health and Wellness to Whalen weekly to talk with students without appointments through a program called “Let’s Talk,” Paulnack said.

Paulnack also said that counselors like Ron Dow, social worker for the Office of Counseling and Wellness, talk to faculty members about how they can best approach students when they are in high-stress situations.

The need for more discussions about mental health among music students led Mikaela Vojnik ’19 to create the Mental Health Awareness for Musicians Association (MHAMA) in 2017. The group aims to promote dialogue and relaxing events for music students to incorporate self-care practices into their college routines.

Sophomore Caitlin Glastonbury, an officer for MHAMA, said the club tries to hold one big event a semester along with smaller community events. Bigger events hosted with other organizations tend to have 10–15 people, but smaller events sometimes only have one or two, Glastonbury said.

“It’s assumed that if you have free time, it’s your practice time,” Glastonbury said. “There’s a stigma about taking a break.”

The School of Music is currently making curriculum adjustments, which will include restricting students from taking over 18 credits, Paulnack said. He said approximately 25 students per semester request to take over the 18–credit limit. Starting next year, he said, students will no longer be able to commit to ensembles for zero credit.

Paulnack said he strives to find a middle ground of pushing students to do their best but also making sure they are taking care of themselves and have balanced schedules.

“There’s challenging students and comforting students, and I kind of want to do both,” Paulnack said. “I say, ‘This is tough, and you’ve got to want to do this, and you have to take care of yourself, and don’t go over 18, and don’t take the class for zero credits, and don’t go do it with three extra things downtown.’”