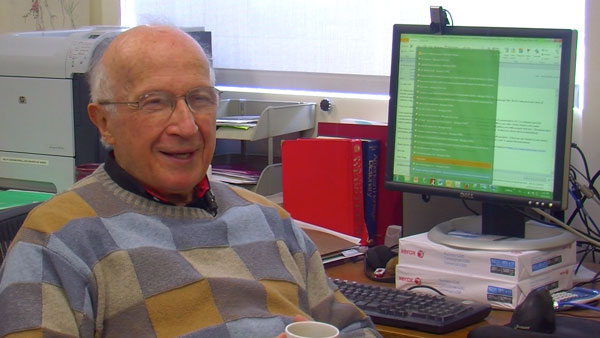

Roald Hoffmann, winner of the 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, will visit Ithaca College next month to discuss his work with protochemistries, a branch of science that explores chemistry before chemists existed.

Protochemistry includes the manufacture of dyes, medicines, metals for hair curling and extracting metals from their ores before chemistry became a science about 250 years ago, Hoffmann said. He will speak at 4 p.m. Feb. 13 in the Center for Natural Sciences, room 112.

Hoffmann, who is also the Frank H. T. Rhodes Professor of Humane Letters Emeritus at Cornell University, left Poland in 1946 with his mother after his father was killed by the Nazis. He came to the U.S. in 1949 and earned his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1962.

Hoffmann has been interested in art and poetry since his undergraduate years, having published several collections of his poems.

News Editor Noreyana Fernando spoke to Hoffmann about his work in protochemistry, his interest in art history and poetry, and his advice to students about making choices in college.

Noreyana Fernando: What aspect of protochemistry interests you the most?

Roald Hoffmann: One reason I am interested in it is because it’s ingenious and anonymous, and it’s interesting to find out how those things were [made]. So it takes a current detective story to unravel what was done in the past. I am also interested because this chemistry is so ingenious, done by ordinary people, families of craftsmen. Somehow, these stories humanize chemistry. Chemistry is not done by people in white coats out there who have to study for X years before they can do it.

NF: How has the role of chemistry changed in society today?

RH: Chemistry has always been there. It looks like we have been put on this earth to transform it. Just the basic winning of metals from their ores, making the raw stuffs of our world, whether it is metals or paint or concrete, you take something that is natural and you transform it. That always was there. It is there, and it always will be there.

NF: What role has art played in your journey?

RH: One way of summarizing what happened to me in college was that I worked up enough courage to tell my parents that I didn’t want to be a real doctor. It was a lot of pressure. I am the only child in an immigrant family, but I didn’t work up enough courage to tell them that I wanted to study history of art or journalism. I just didn’t have it, but I was interested. So I went into chemistry. It was a compromise. I didn’t decide on being a chemist professionally until halfway through my Ph.D. in chemistry. But I have kept alive these other interests in writing, so I feel that I am a writer also, and I write poetry, plays, novels, nonfiction.

NF: What are your inspirations for writing?

RH: In poetry, I write about the things that poets usually write — of love, of nature, about emotions. I also write about science, and that is not perhaps typical, and it’s the hardest thing. I thought it would be easy. It’s part of me, after all.

NF: Why is science so hard to put into a poem?

RH: A lot of science is inherently prosaic, not poetic. It’s all about all the conditions that have to be met in order for the regularity or law to hold. But it’s all about the exceptions. That’s why we have all these footnotes and endnotes in scientific paper. That’s not what poetry is about.

There are other things which are difficult. A lot of science is about the universal, so you want the equations like e=mc2. A lot of poetry is about particulars — you see a drop of dew on a blade of grass when you go out in the morning, and it’s that particular blade of grass and that drop of dew. You couldn’t care less about the biochemistries of the grass or what goes into farming the water.

NF: You once said chemistry is art. Do you think interdisciplinary studies are important?

RH: First of all, at university or college, your world is opening up before you emotionally, in personal relationships as well as in these courses. You can do much more reading than you can do later in life. It’s a wonderful time for exploring the universe. The world is opening up. You might have read a novel by Ernest Hemingway in high school. But reading it at age 21 in college, it means something different. Probably, you have been in love since that time. A few years can make a world of a difference in your emotional perception of a work of art. Those distribution requirements are the greatest thing that’s happening to you.

NF: What advice would you give to college students making life decisions?

RH: It is much easier to make a living as a chemist than as a poet. You do have to take that into consideration. Your parents, especially if they are immigrants — which is true for many students — they are very concerned about having an education that’s portable. But you have to do what you like doing. And you also have to satisfy a need that every human being has for some passion, something spiritual in their lives. It could be a religion. It could also be reading or writing poetry, listening to music, taking care of a sick parent. But all of these things make you a complete, whole human being.