Editor’s Note: This is a guest commentary. The opinions do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial board.

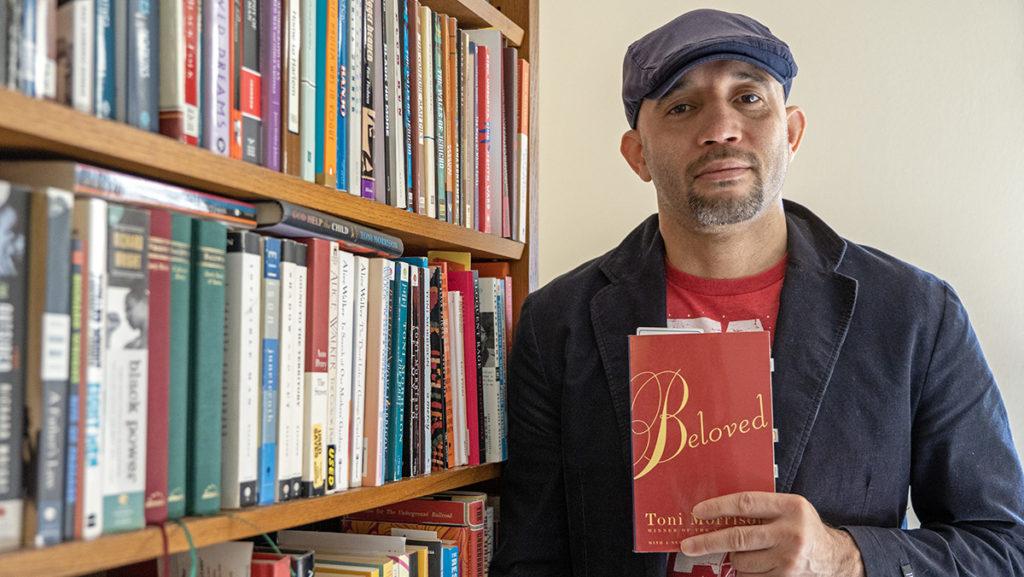

Last March, I was invited by Christine Pearl ’11 to facilitate a book club session on my second favorite Toni Morrison novel, “Beloved.” The session was an extension of the efforts of the nonprofit organization Red Wine & Blue, whose mission is to empower and educate suburban women to fight back against book bans across the U.S. Hundreds of members attended the virtual meeting held at 8 p.m. March 22, 2022, all of them eager to hear about and share their own feelings on the majesty of Morrison’s Nobel Prize-winning masterpiece. These women set aside important obligations, sacrificing time and making space to grapple with a profound, complicated novel that centers our collective reckoning with the enduring ramifications of enslavement on the enslaved. Their enthusiasm and commitment to do this work as part of a book club makes me wonder why anyone would attempt to ban such an important work of literature. The novel is demanding of readers; we all could have shied away and claimed to have better things to do. Not one of us chose to. Proponents of book bans fail to understand a paradox that censorship creates: Attempting to restrict access to any book has the potential to set ablaze an even greater interest in it.

Recently, Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law and other similar efforts at all levels of government to restrict access to LGBTQ+ stories in schools have continued the decades-long effort to diminish those whose lives do not conform to cultural norms around gender and sexuality. One oft-cited argument is that exposure to such stories will turn the children reading them gay. To be clear, reading LGBTQ+ stories has not, and will not ever, be what turns someone gay, queer or trans, just as reading “Atlas Shrugged” did not make me into a libertarian, nor “The Handmaid’s Tale” into an incel. No story has ever had such power. But LGBTQ+ stories can show someone who is contemplating the contours of their gender and sexual identities a variety of expressions of attraction and forms of relationships that create an even greater possibility for their personal joy and intimate fulfillment.

LGBTQ+ stories also give us a much more holistic account of the human experience, which lies at the heart of why we read stories. Proponents of book bans lean heavily on the rhetoric of a parent’s right to choose; in this case, they argue that parents should get to determine how their child is exposed to issues connected to gender and sexuality. The problem with this idea is that every child is exposed daily to these identities: nuclear families on TV and in film, couples hand-in-hand walking down the street, product packaging, advertisements, classic children’s books. Cisgender heterosexuality is in everything we do, including the language we use to communicate. Yet, it is only one story of identity we are privileging when there are so many others for us to know. I am a cis-(mostly)hetero man who reads and teaches several texts with LGBTQ+ characters and storylines, primarily because they bring me joy. These works also provide me a window into the lives of people who identify differently than I do, which I sincerely believe continues to grow my capacity for empathy. In opening myself to the works of James Baldwin, Kacen Callender, Alison Bechdel, Carmen Maria Machado, Audre Lorde, ZZ Packer, Akwaeke Emezi and dozens of others, I have learned how writers different from me understand, center and articulate the humanity of the characters they imagine into existence. Immersing in their “banned” books is personally transformative. Reading them, I feel self-reflective and am eager to seek out new connections. It makes me less afraid of what I don’t already know. At this point in our history, it is difficult to imagine anything more important than connecting across boundaries and opening ourselves up to different points of view.

It should go without saying that a restriction of available choices never serves as protection of the right to choose. What we know for certain is that reading a book only makes one a reader. To think otherwise is to view reading passively, as something the writer does to a reader through their book. Rather, reading is something done actively; readers and books work in tandem to explore the nuances of being human.

Reading is a foundational element of my relationship with my two sons. We read LGBTQ+ books together because they illustrate stories of people they may become, people they may love or befriend and people they may never meet. Each is as important as the other.