Music has a way of representing and preserving certain moments in a person’s life in a way far different from the way other memory cues do. In the same manner that music can work as a memory aid, music can work as medicine, as one new service-learning program at Ithaca College shows.

The Music as Medicine Project — a collaboration between the School of Music, the Gerontology Institute, the Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies, the Office of Civic Engagement and the Center for Faculty Excellence — highlights the therapeutic power of music and the importance of service-learning. The initiative emerged from conversations between the Gerontology Institute and the School of Music during the fall semester.

According to the national organization Music & Memory, the brain and music are tightly linked. Music is often associated with certain episodic memories and acts as a recall cue for memory. For older adults and those struggling with diseases of memory impairment, such as dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, music can act as a powerful memory aid and bring comfort and healing to affected individuals.

The science behind this link has been verified over the years, and the practice of the therapeutic benefits of music dates back to just after World War I and World War II, when practitioners used music to heal and engage veterans.

According to the American Music Therapy Association, music can help increase or maintain patients’ physical, mental and emotional functioning. Music stimulates the senses and cognition and can be used to heal people across many spectrums, including those with Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Renowned neurologist Oliver Sacks conducted notable research dealing with music and memory. In a video discussing his book “Musicophilia,” Sacks said despite severe memory impairment, virtually everyone’s memory responds to music, and music can be a reawakening for those who have lost their pasts and their identities.

“A common thing in Alzheimer’s is to lose one’s memory for events and really to lose one’s autobiography, to lose one’s personal memories, and they can’t be accessed directly,” Sacks said. “But personal memories are embedded in some extent in things like music. … People can regain a sense of identity, at least for a while.”

Sacks said this is because music, especially familiar music, can trigger memory and communication in the brain for those who have lost the ability to tap into their former selves.

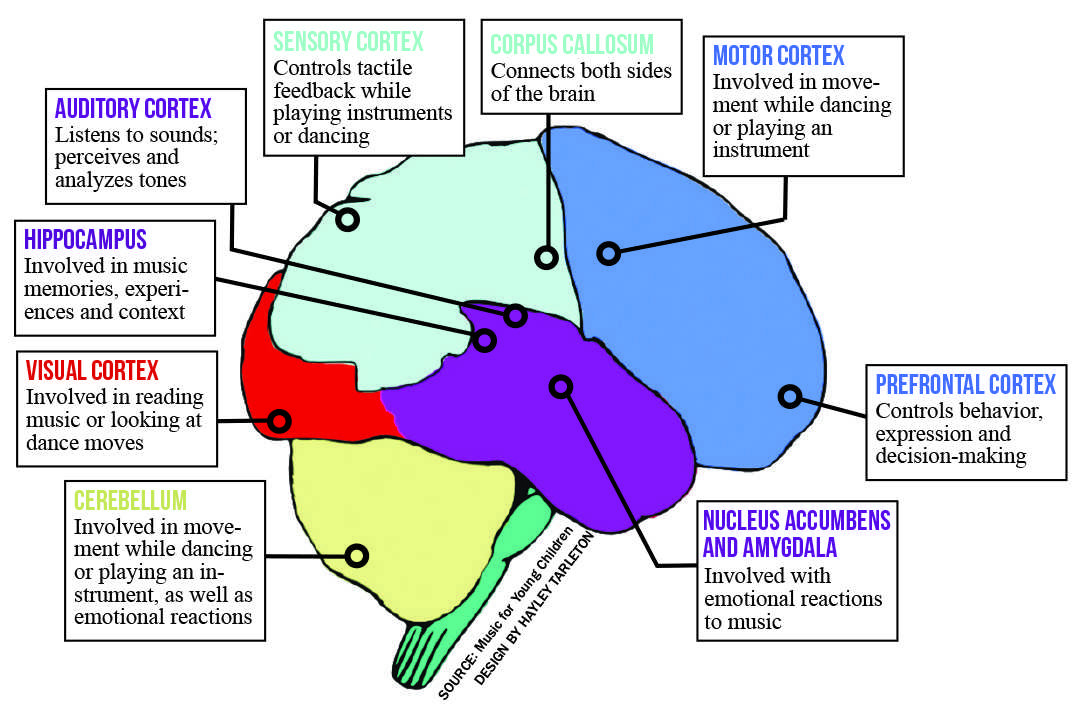

“The parts of the brain which respond to music are very close to the parts of the brain concerned with memory and emotion and mood, so familiar songs will bring back memories,” Sacks said.

Patricia Spencer, assistant professor and faculty director of service-learning in the Office of Civic Engagement, said music can be an integral key to connecting with older individuals in a way that other therapies cannot.

“One of our last memories that we hold on to is our musical memory,” Spencer said. “Even as seniors start to lose some of their ability to communicate, if you can reconnect with musical memory, they sometimes will find language again, and they can talk about that music or where they were at the time they heard that music, why they love that song.”

The Music as Medicine Project works with this knowledge to substitute overmedication of patients in favor of music therapy.

The initiative emerged from conversations among the three academic departments about the work of Music & Memory. That idea has since blossomed into three classes in the separate disciplines, a student organization and several other service-learning pro grams.

grams.

Students in both the Service Learning II course taught by professor Linda Heyne within the Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies and the Gerontology Institute’s course Fieldwork in Gerontology work with senior citizens with dementia and Alzheimer’s using recorded music and iPods to create personalized playlists as a form of musical therapy. The School of Music’s course for this program was Exploring Music as Medicine — Using Music to Benefit Health Care Settings, taught by associate professor Elizabeth Simkin. During the class, students engaged patients in performances, sing-alongs and sharing musical memories.

“We focus on using live music to shift the energy of people we bring it to. We’re trying to restore a sense of wholeness, whatever that means for them,” Simkin said.

Ryan Mewhorter, a freshman voice performance major, has seen the effects of music therapy firsthand.

“When I was younger, my grandfather was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and could not remember much but could sing every word to Ave Maria and would light up when he did,” he said.

Mewhorter is president and founder of the student organization Music as Medicine, which emerged from this initiative and was officially recognized at the beginning of this semester. Mewhorter said he was inspired to create the group in response to an event held by Music & Memory at which the organization presented.

Like the overarching initiative, the student organization works with music as a form of medicine for those with dementia and Alzheimer’s, as well as autism, and he said he hopes to see the program and research spread to other contexts and have an impact beyond the college.

“It is in my opinion that this project will be something that will seriously affect the way that we look at diseases that affect the brain, and I think it will show the importance of music as a part of education either as a performance aspect or even looking at it through a scientific view as well,” Mewhorter said.

Along with the rest of the Music as Medicine initiative, Simkin’s course will be expanding next year and continue to allow music students to push beyond themselves and make a greater impact on the community through service-learning.

“People need music desperately, and I think the community is getting the richness of this benefit, and equally, our students are having the experience of what music can bring,” Simkin said. “Sometimes, when we don’t get out and share it with people who are hungry for it, music can have a lot of concern for the self. But when we have this experience of sharing music with someone who needs it desperately, we say, ‘Wait, this isn’t about me, not at all.’”