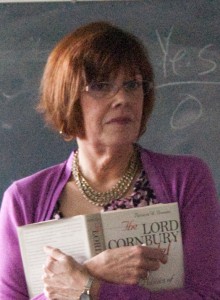

Below is an excerpt from an essay titled “‘There Is Graite Odds between A Mans being At Home And A Broad’: Deborah Read Franklin and the Eighteenth-Century Home” written by Vivian Conger, associate professor and chair of history. The essay appeared in “Gender & History” Volume 21, Issue 3 (published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd.) in November 2009.

During the 44-year marriage between Benjamin and Deborah Franklin, his work frequently took him away from home for long periods of time. On Nov. 8, 1764, Benjamin departed from Philadelphia for England, their longest and final separation (she died six months before he returned). It was a separation in which she increasingly assumed the male persona of the Franklin household. Luckily for historians, they carried on a steady correspondence. It is through these exchanges that we glimpse a normal give and take between husband and wife. But more importantly, this correspondence reveals several literal and figurative gendered reconstructions embodied in their home.

The Franklins began building their own house in the spring of 1763. By the time Benjamin left for England in late 1764, the framework had been erected. The house represented two spheres: exterior and interior, public and private, strength and weakness, masculine and feminine. Deborah turned that order upside down.

The most radical re-gendering of the house came on the night of Sept. 16, 1765, when the house took on an overtly political and military significance. Angry responses to the Stamp Act occurred throughout the colonies, but many in Philadelphia blamed Benjamin for supporting the act, and mobs threatened to retaliate. From Deborah’s description of the situation, one can feel the tension and perhaps even fear she felt, but also more palpably the strength, control and bravery she exerted. For nine days people kept warning her of the danger she and her family faced. Tensions reached the boiling point when the mob threatened to pull down the newly built house. But she did not face them alone. “Cusin [Josiah] Davenporte Come and told me … it was his Duty to be with me,” she said. She seemed to have control of the situation, however, for she ordered Davenport to “fech a gun or two as we had none.” It is not clear which one of the elegantly furnished and decorated rooms became an armed fortress, but clearly all of the second-story private bedrooms became more than feminine domestic spaces. Later that evening, more than 20 relatives and neighbors helped guard the house. Despite their offers to stay the night with her, she sent them away.

As her supporters left, they urged her to leave with them, but she refused, adamantly asserting, “I had not given aney ofense to aney person.” Refusing to be intimidated and putting on a brave face to the outside world, she proved she could protect her household. When Benjamin’s reply came several months later, it was notably brief; he wrote simply, “I honour much the Spirit and Courage you show’d, and the prudent Preparations you made in that [Time] of Danger.” Then he added this intriguing comment: “The [Woman] deserves a good [House] that [is] determined to defend it.” In Benjamin’s mind, had Deborah finally demonstrated enough courage and enough masculine qualities to begin defining the house as hers?

The image of armed women protecting themselves was not new, but the “female soldier” lived at the margins; she was not a genteel lady living in the heart of a city in a newly constructed house designed to prove her family’s status to others. Historians have argued that because men’s houses symbolized their authority and their manhood, those structures “became target[s] of popular anger” when leaders attempted “to enforce what the people considered to be illegitimate laws.” Defacing the most visible symbol of their political manhood, the mob demonstrated their disrespect for revolutionary leaders. When defending the house, Deborah was not just protecting her household — her feminine private domain — she also was defending her house — her masculine public domain.

Vivian Conger is an associate professor and chair of the history department. E-mail her at [email protected].