Josh Ritter follows the journey of a World War I veteran in his debut novel and shows he can change artistic mediums without losing his way with words.

Ritter’s “Bright’s Passage” tells the story of Henry Bright, a veteran who has to leave his West Virginia home with his newborn son to escape a forest fire.  An angel Bright meets at war speaks through a horse to guide him through his travels.

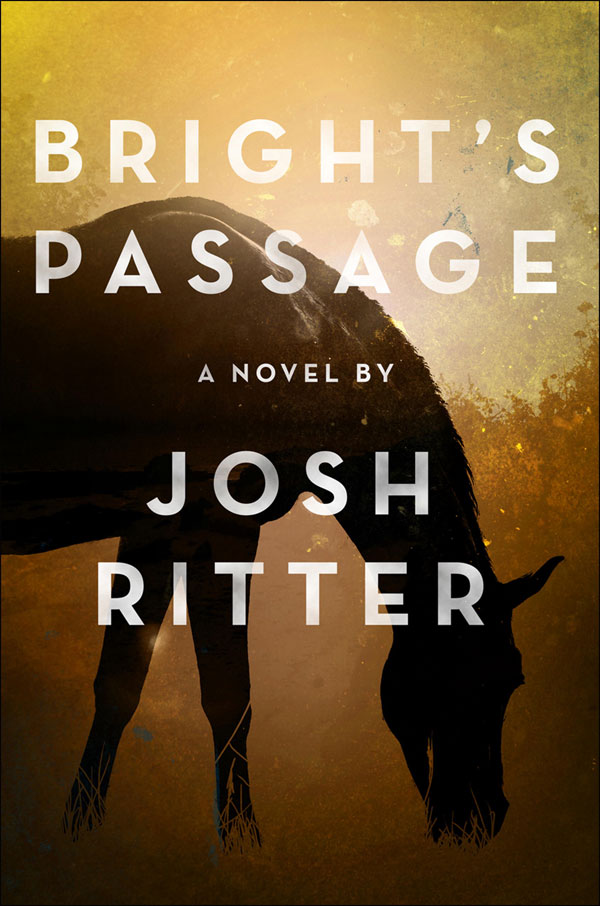

An angel Bright meets at war speaks through a horse to guide him through his travels.

For anyone who has heard Josh Ritter’s music, it is impossible to read “Bright’s Passage” without comparing it to his songs. The similarities between the novel and the music lend themselves to an enjoyable experience for fans of both.

“Bright’s Passage” echoes the sparse, lyrical nature of Ritter’s best work, like the storytelling songs on his 2006 album “The Animal Years” or his most recent work “So Runs the World Away.” It creates an atmosphere that fits the long, arduous journey Bright must make. The content is also familiar as Ritter’s music often features angels — particularly those of questionable morality.

The novel is not laid out chronologically, but with multiple parallel timelines. Alternating chapters depict Bright’s time at war, the year he spent with his young wife before she died giving birth to their child and the present, where he takes orders from the angel he is not certain he can trust.

The flashbacks to Bright’s time as an American soldier in the French trenches during World War I are the highlight of the multiple narratives that weave in and around each other throughout the novel. The war-torn landscape and low morale of the soldiers create a stark, realistic background for Bright’s introduction to the angel and the beginning of his journey.

In the story’s weaker moments, it seems like the author tried to stretch a five-minute song into a book of about 200 pages. Some passages become heavy with unnecessary description. Luckily, these moments are rare and in most instances Ritter’s longer passages describing the trek through the forest, and the anticipation of battle during the war, make the reader feel as tired and weary as Bright himself.

Despite this, the majority of “Bright’s Passage” is a tightly written, quick read that delves deep enough into Bright’s past to create a character who is stubborn, headstrong, rational and just faithful enough to trust the angel who tells him he has a destiny to fulfill.

Even with an angel giving guidance through an animal, the focus of “Bright’s Passage” is on feeling, not fantasy. Bright struggles with the morality of war and fitting into his old life after his return from Europe. He suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder and the grief of losing his wife, but is forced to move forward in order to take care of his child.

The angel — who is never assigned a name — remains aloof throughout the story. This makes the humanity of Bright’s struggles — which are vivid and detailed unlike the angel’s mysterious history — more realistic in contrast to the angel’s otherworldly nature.

There is nothing particularly groundbreaking about “Bright’s Passage.” It’s not the first story to feature a post-war time period, angels, talking animals, journeys or moral conflict. And it certainly isn’t the first novel to be written by a folk-rock musician as Ritter joins the ranks of Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan and several others who have attempted to translate their stories from song to passage.

What makes Ritter’s novel worth reading is its emotion. The novel is a promising first look at a writer already known for his ability to tell stories in another medium, and to peruse its pages is a journey worth taking.

Visit http://joshritter.com/music to listen to song clips from Ritter’s albums “The Animal Years” and “So Runs the World Away.”

3 out of 4 stars