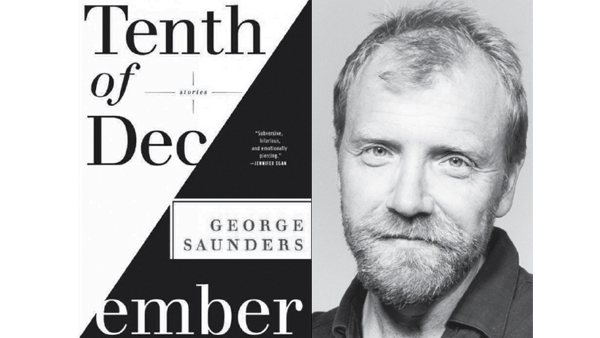

If the creative muses of “Catch 22” author Joseph Heller and “A Clockwork Orange” author Anthony Burgess got pathetically drunk and had a one night stand, the result would be something like George Saunders’ new book “The Tenth of December.” Mark Twain would serve as a fitting godparent.

“The Tenth of December” is a collection of 10 short stories that create a timely social satire and a nearly complete guide to being a decent moral person. In the book, Saunders tackles the basics: love, lust, patriotism, fear, relatives that don’t care enough and friends who care less. He attempts to drive home the flaws of the American characteristics with short words and simple characters — a tall task to say the least.

Saunders doesn’t waste time creating thick, intricate plots. For the most part, his characters are easy-to-digest silhouettes of the stories we all know. In “Victory Lap,” a suburban daughter is abducted and then saved. Her story includes all the normal violence associated with modern search and rescue missions. In “Al Roosten,” a former high school loser struggles with unyielding envy of the richest man in town.

The narratives, in their predictable simplicity, provide a base for a collective idea of what’s right and wrong. Saunders allows the reader to insert context and build personal meanings from the stick-figure characters he uses as puppets to illustrate human shortcomings. Even the characters meant to represent the moral downside of typical American life, like the jealous neighbor, have a tragic element that inspire more sympathy than disdain. Rather than encouraging his readers to hate the people who fall short of moral goodness, Saunders gives a reminder that moral flaws are human and natural.

One exception to Saunders’ trend of creating simple stories is “Escape from Spiderhead,” a dystopian futuristic story in which scientists develop drugs that create overwhelming emotions of love, lust and despair with trademarked names like Darkenfloxx and Vivistif. The narrative calls into question the ability for science to triumph human emotion and the legitimacy of love and loss. The short story ends in a voluntary emotional breakdown of its main character.

Saunders managed to write a full book without producing one possible plot spoiler. Nothing shocking happens and nobody is worse-off for it. The returning war veteran loses his temper with his dysfunctional family, a suicidal man is inspired by the opportunity to save a youngster and a neighbor acts on his jealousy of the rich former high school bully that now lives in a mansion in town. Because we’re not waiting around for something to go bump in the night, the narrative begs the reader to fill in the gaps and realize these stories, told again and again, are the cultural backbone of American moral behavior.

In “Home,” war veterans gather to talk about their time in combat. One former soldier admits he accidently hit a dog with a forklift. He assures his friends the dog survived and forgave the soldier enough to ride alongside him again in the forklift. The soldier then admits he was the reason a comrade was hit with shrapnel — he again assures his friends no lasting harm had come from his accidents. His friend responds he’s glad the wounded comrade survived and says, “Probably he even sometimes rides up alongside you in the forklift.” By calling attention to the soldier’s trivial approach to violence and forgiveness, Saunders highlights a flaw in the American mindset regarding the social treatment of people in combat. The desire to deem injured soldiers healthy when it may not be that simple is examined.

Though “The Tenth of December” is a worthwhile read, Saunders fails to produce a work that will leave a new mark on the face of good satire. The book is more of the same witty, dark humor Saunders is known for. While it shows traces of the genius inspired by writers like Heller, Burgess and Twain, this book isn’t likely to become a quick classic in an already cluttered genre.