Amii Omara-Otunnu, the UNESCO chair for the U.S., visited Ithaca College on Monday night, where he discussed contention between government and human rights in the 21st century.

Omara-Otunnu has worked in Israel, Western Europe, North America and other regions. He is the founder and executive director of the Institute of Comparative Human Rights at the University of Connecticut, where he is also a professor.

About 30 students gathered to listen to Omara-Otunnu in the VIP room of the Athletics and Events Center. Sonali Samarasinghe, scholar in residence at Ithaca College, organized the event as part of a lecture series connected to the course she teaches on Human Rights Litigation. The Honors Program and the departments of history and health promotion and physical education co-sponsored Omara-Otunnu’s lecture.

Robert Sullivan, director of the Honors Program, introduced Omara-Otunnu’s academic interests and work before inviting him to speak.

“Otunnu is more than a successful academic, he is also a practical visionary,” Sullivan said. “He has devoted his life to the cause of human rights, to promoting democratic pluralism, equitable development and social justice around the world.”

Omara-Otunnu walked up to the podium with no papers or notes. He said he did not prepare a speech out of respect for the audience.

“In the spirit of the conversation, [I want] to speak as the spirit moves me,” Omara-Otunnu said.

The interdependence of global community, which he said is also the foundation of the globalized ethical value he envisioned, was the first thing Omara-Otunnu talked about.

“Today we live in a world that is increasingly interdependent, a world in which ‘global village’ is no longer a metaphoric expression, it’s a practical reality,” Otunnu said. “We are only one human race, not many races. The challenge of [the] 21st century is how do we conduct ourselves in a way which is commensurate to the reality of this world we live in.”

Omara-Otunnu said the poor understanding of the interdependence of the global community results in the lack of sympathy for the victims of human rights violation.

“There is a gap between the rhetoric of what we say and how we conduct ourselves, ” Omara-Otunnu said. “We use human rights to measure how government conducts their affairs, but unfortunately we conduct ourselves in a way as though human rights is not attached to our own lives. ”

Omara-Otunnu said sometimes the way people approach human rights issues is problematic, because they do it out of pity. He said “informed empathy” needed to be achieved first as a better approach to human rights issues.

“We manage to focus our attention on globalized maximization of profit, globalize everything except for ethical values,” Omara-Otunnu said.

He also elaborated on how “informed empathy” helps solve human rights violations.

“We can develop it by opening an imaginative mind,” Omara-Otunnu said. “We can develop a capacity to put aside our own interests and put on the interests of others to be in their shoes. If any of us develop this informed empathy, any of us would know that woman that was raped could easily be my daughter, my mother or sister and what do I do about it. ”

Omara-Otunnu then made the connection between violence and power, saying the only way to domesticate power is to globalize ethical values.

Toward the end of his speech, Omara-Otunnu brought up his expectations for the younger generation.

“To begin to live with empathy towards one another, to keep on dreaming,” Omara-Otunnu said. “Dreams are the essences of human existence. Too often in history, people who were thought to be dreamers are the ones who change the world. The pragmatists are the ones who allow the status quo to continue.”

Following the speech, Omara-Otunnu answered some of the audience’s questions. Matt Mogekwu, associate professor of journalism, expressed his concerns about the globalization of values, as he thinks such processes will take too long, and it’s hard for all people to reach a consensus on one globalized ethical value.

“[The globalization of values] is going to take two, three, four, five, even six generations to bring about, not because it is impossible, but because those who have developed theories about ethics have given us theories to justify whatever they do,” Mogekwu said.

Omara-Otunnu said he thought the point Mogekwu was raising was an important one.

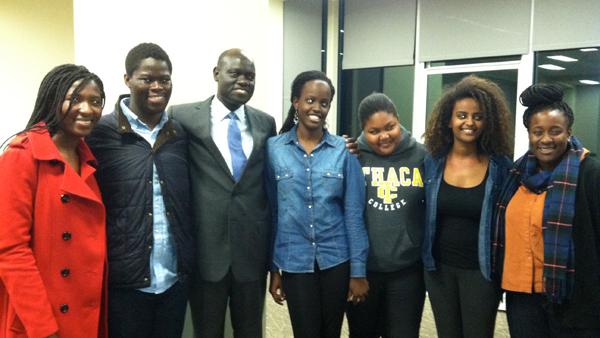

He also lingered after the lecture to speak with students and faculty members.

Sophomore Anna Gress said the speech was motivational, because it made her think about issues that are broader than her own self.

“It makes you think outside of your selfishness, that there is a bigger problem in the world that needs to be addressed, and it makes you want to go out there and do something,” Gress said. “It definitely gives you a lot to think about. ”