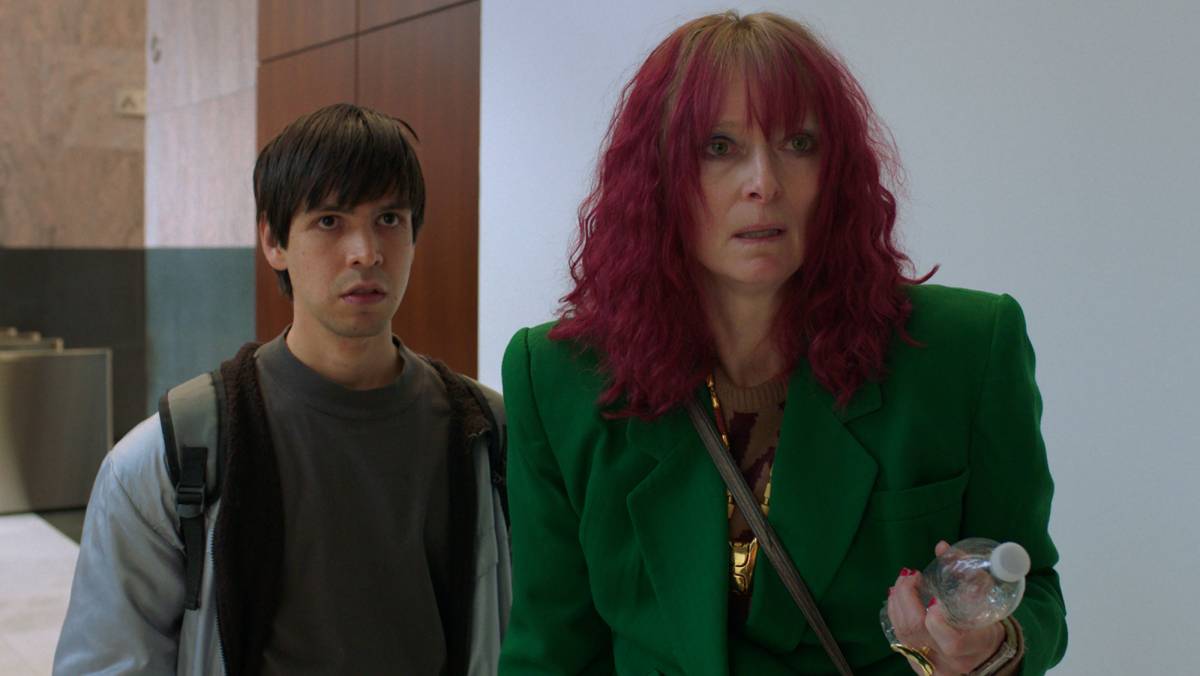

In “Calvary’s” opening scene, a priest is told through a confessional’s dividing wall that he will be killed in one week’s time. It’s a blunt statement, made even more jarring by the motivation and rationale attached to it: The act is revealed to be retribution for past abuse, but the threatened priest has no such wicked backstory. As the prospective killer sees it, there’s no use in murdering a bad priest but killing a good one is bound to get attention.

With “Calvary,” writer and director John Michael McDonagh takes a bold step into new territory. A far cry from his uproarious, buddy-cop debut, “The Guard,” the film plays as a solemn drama. Scenes are often tinged with black humor, but the aim is consistently set upon achieving greater philosophical weight. Outdoor sequences are accompanied by overcast skies and subdued color tones. Brief moments of broad hijinks are countered with stern looks as a portentous score looms over the picture, suggesting a journey of religious overtones and moral heaviness. McDonagh wrote the script for “Calvary” prior to directing “The Guard,” and the finished product bears the trademark of a newcomer’s passion project. Ambition often welcomes greater thematic troubles than the likes of McDonagh’s previous summer romp, and while it would be a stretch to call the director’s sophomore outing a misfire, it must be noted that some of its ideas lack coherence.

After the initial confessional conversation, the film follows our protagonist, Father James (Brendan Gleeson), in his day-to-day travels. He’s been given a week to put his house in order, and he uses the time to engage with the numerous abrasive personalities that populate the Irish seaside village. A long string of dialogue-heavy scenes comes from this, and McDonagh doesn’t allow the film much room to breathe in between the incessant chatter.

One-on-one exchanges concerning topics of suicide, self-worth, loss, regret and surrender among other things take up the majority of the runtime. After nearly an hour of it, the effect is more monotonous than fascinating. The last act offers a handful of intriguing dream sequences and striking images to break up the sameness of the conversation setups, but by this point, the necessary story development is somewhat lost, so the finale lacks the proper impact.

Despite the endless encounters with quirky characters and a tendency to cover all bases with a broad array of themes, “Calvary” remains mostly engaging due to Gleeson’s central performance and the application of the film’s prevailing message. The role of the good-hearted, but troubled clergyman is one that has been seen before, but it takes a certain quiet, yet commanding type of screen presence to pull it off. Thankfully, Gleeson is perfect for the part. He plays Father James with a world-weariness that only amplifies as the film progresses. The character possesses sharp wit, but he resorts to kind consideration more quickly than cynicism. His resolve to positively affect the community is gradually worn down as the people around him rarely take his words seriously. Playful derisions abound, and there’s a general apathy and distrust of the cloth that was once strictly respected.

In these characters, McDonagh presents a country that has become disillusioned with the church and wants little to do with it. They’re all sinners, but they care not for the one man that tries to save them. Father James isn’t a saint, but as alluded to in his frequent visual juxtaposition with a prominent mossy landmass, he stands out among the last of a dying breed in a nation requiring absolution.

“Calvary” is a film of resounding bleakness. Most of its attempts at levity fall flat in the wake of the depressing narrative, but cinematic joy is easily found in the mastery of Gleeson’s performance, the thoughtfully composed visuals and a few of McDonagh’s thematic musings. Like Father James, the film is imperfect, but it represents an interesting new direction for a still-budding filmmaker and is worth seeing for the promise it holds.