A survey of the service load of Ithaca College faculty members conducted in Spring 2018 indicates that faculty of color perceived they were doing more service work than their white counterparts and that female faculty reported slightly less service than male faculty. However, national experts and faculty on campus are questioning the validity of the survey results.

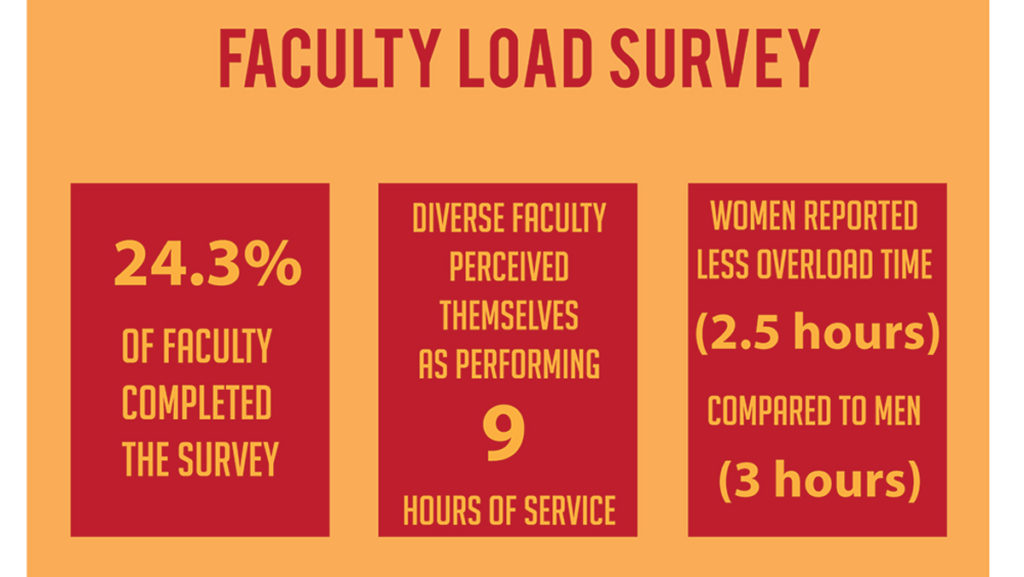

Approximately 25 percent of faculty responded to the survey, and the results were presented to the Faculty Council by David Gondek, associate professor of biology and member of the council. Of the 178 faculty members who completed the survey, 68 respondents were male, 95 were female and the remainder did not specify a gender. In addition, 156 respondents were white, and 22 were ethnically diverse. As of Fall 2018, there are 721 faculty members at the college.

The survey showed that faculty of color reported an average of nine hours of service a day, whereas the overall faculty average was 2.3 hours per day. In addition, the survey results showed that female faculty reported an average of 2.5 hours of service time while male faculty reported three hours. The Ithacan has previously reported that female faculty and faculty of color often spend large portions of their time working with students and providing emotional support for them.

Gondek said the council did not create the survey with a specific goal in mind, but the council did want to collect data on inequities in workloads. After the survey was created, it was reviewed by the Faculty Council Executive Committee. Gondek said the survey was available to faculty from Feb. 26, 2018, to May 31, 2018, through an anonymous link, and that Tom Swensen, professor and chair of the Department of Exercise and Sport Sciences and chair of Faculty Council, sent “multiple” reminder emails for faculty to complete it.

Gondek said the survey was initiated by 50 percent of faculty but was only completed by approximately 25 percent. He said the complexity of the survey was probably the reason for the low completion rate.

“The completion response rate was acceptable, but more would have been better,” Gondek said. “Faculty service is complex, and a simple survey, which might have received a higher response rate, would not be able to capture the many different activities that faculty complete for service on campus.”

Gondek said the results are not a perfect representation of faculty workload and do not prove anything conclusively.

“These data are a good place to start the conversation on service load for faculty as a whole,” Gondek said. “I do not believe these data are representative when subsets of faculty demographics are examined. Further work would be needed.”

“Cultural taxation” is a term coined by Amado Padilla in 1994 and describes the extra service burden that faculty of color have at predominately white institutions. Faculty of color have reported often feeling obligated to serve the institution on committees or in situations in which the institution needs to show recognition of racial or ethnic diversity. If the representation of diversity on the committees is higher than what is represented in the population of the college, the same faculty of color are repeatedly asked to serve on more committees than their white counterparts. In past reporting, The Ithacan found that women at the college experience a similar service burden.

Deborah Rifkin, associate professor in the Department of Music Theory, History and Composition, said the results of the survey pertaining to the reported amount of service work women faculty complete at the school was not what she had expected.

“I am very surprised to hear that one of the results of the survey is that women report less service,” Rifkin said. “I know that I have been put on committees with good intentions that they wanted gender balance on committees without having gender balance in the faculty.”

Rifkin said that unless the makeup of the faculty as a whole matches the makeup of the committees, there will always be uneven service burdens.

“It’s just a reality that if you want gender balance and the demographics don’t support that, then some people will be doing more service,” Rifkin said.

Tiffany Joseph, associate professor of sociology at Northeastern University, said her research about the experiences of female faculty and faculty of color show that they typically bear the burden of having to represent their genders or ethnicities in various roles on campus. Her research mainly focused on the experiences of women in STEM fields.

Joseph said that because faculty of color are typically underrepresented and the college is a smaller institution, the results from the faculty workload survey may be too small to be accurate.

“Given that you’re at Ithaca College and there’s likely a small number of faculty of color, I’m guessing the sample size is probably too small to have any statistically significant response from faculty of color,” Joseph said.

Cecil Canton, professor in the Department of Criminal Justice at California State University, Sacramento, co-authored a book called “The Politics of Survival in Academia: Narratives of Inequity, Resilience, and Success.” He said that when institutions continually request that faculty of color to do more service work, the faculty’s ability to focus on other aspects of their professional lives is diminished.

“If I am going to be evaluated based on my research and scholarships, but you’re putting me on every committee because you want to show that you have diversity, then I’m going to have a higher workload than folks who … don’t have that same burden,” Canton said.

Canton also said the small sample size might make it difficult to draw conclusions.

“That’s a very small number to base a sweeping generalization,” Canton said.

Gondek said it was possible the data was skewed because some respondents might have misinterpreted how the hours of service were measured. He said he intended for time measurement to be in credit hours, as it written in faculty contracts.

“In the contract, faculty are provided with a certain number of credits or their perception of how many credits of time they’re doing service,” Gondek said. “Some faculty misinterpreted that.”

Gondek also said there was a wide range of individual responses when it pertained to service.

“There’s a lot of variation,” Gondek said. “Some individuals are doing a lot of service; some individuals aren’t doing much. We didn’t want to look at it on an individual level. We wanted to look at the aggregate.”

Sergio Cabrera, assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at the college, said it is difficult to know if the results of the survey are accurate because the faculty’s reasons for completing the survey are unknown.

“It’s hard to know without knowing how that 25 percent reflects the faculty generally,” Cabrera said. “For example, if the 25 percent who did fill it out did so because they had time to fill it out because they weren’t mentoring or if the 25 percent filled it out because they felt they did a lot and wanted recognition for their work. In either case, it would be heavily biased, and add on top of that the fact that it was self-reported.”

He said he was not surprised to find that the survey reported that many professors at the college put in extensive service hours.

“It particularly doesn’t strike me as surprising as a sociologist because I know that there’s a certain amount of care work that gets wrapped up in mentoring or taking time to meet with students outside the classroom,” Cabrera said.

Cabrera said he feels as though he does care work for his students. He said students come to him to discuss personal topics like relationship issues, roommate problems, complicated family dynamics and their experiences as students of color at a predominantly white institution.

“It ranges from that to ‘My ex-boyfriend is stalking me. What should I do?’, ‘My roommate is bringing random people around. What can I do?’ or just sort of needing to vent,” Cabrera said. “It’s ‘My mom is on one of her episodes again, and I’m struggling to cope with that,’ ‘I’ve always been an A student, and this semester I’m getting C’s,’ or ‘It’s hard being the only black person, Latino person in class,’ to “I’m feeling a certain way because my professor is using the N-word.’”

He said it can be challenging to know when the formal work the faculty is paid for ends and the care work that faculty do for students begins. He said this is because faculty care about the well–being of their students and their success throughout their time at the college.

Cabrera said he thinks that in many instances, much of this work falls on the female faculty and faculty of color as well as younger faculty.“This kind of care work often falls to female faculty, faculty of color and younger faculty who tend to already be in more precarious positions in terms of job stability and pay, and so this kind of work can exacerbate already existing inequalities,” Cabrera said.