September is National Suicide Prevention Awareness Month and the same month as the birthday of my father who took his own life. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevetion, suicide rates continue to rise in the U.S. Suicide has ranked as the 10th leading cause of death since 2008 — and, in 2016, suicide ranked as the second-leading cause of death for people aged 10 to 34 and the fourth for individuals aged 35 to 54. Although each suicide gravely impacts at least six people left behind, I rarely hear or read stories of the suicide loss survivors. This is my story that I would like to share.

Self-inflicted (adj.): “a self-inflicted injury, condition, etc. is one that you cause yourself.” When I was 7 years old, my childhood friend and I struggled to figure out the meaning of “inflicted” as part of “self-inflicted wound” while looking up the word in the dictionary. We understood “self” and “wound” (although we couldn’t figure out what type of wound it was), yet the definition of “inflicted” was daunting. We were confused by the cause of death stated in my father’s death certificate that we found in an old briefcase under my mother’s bed. It was a rainy day, so our bicycling plans changed to rummaging around my mother’s cluttered bedroom. And the cause of his death was quite different from the car accident my mother had told me about.

I never knew my father; he died when I was 3 months old. However, I’ve known his absence all my life. Remnants of his life survived in the battered briefcase and two trunks in the attic, along with some gifts he gave my mother, their wedding album and faded snapshots.

My mother talked about what life would’ve been like if he were alive. She painted fantasies of a lovely house overlooking the ocean in Monterey, California, where they were planning on moving to. And I could see myself as a surfer girl mastering the waves. And when the reality set in that we would continue living in her parents’ old two-family house in a small Hudson Valley town, my mother began lecturing with the mantra, “don’t rely on anyone but yourself.” As an undereducated high school dropout, my mother was once proud to have married someone with a college education, a steady job and a seemingly promising future.

My family discussed my father as if he never existed. The exception was when a few relatives visited Hawaii, where I was born and where he died, and brought back photos of his gravesite. My mother broke the news to me when I was 14, figuring that I was old enough to understand the truth. I had never told her about my discovery on that rainy day. I think she was surprised that I was not upset, while not realizing that I had seven years to reflect on it. Frankly, it took me years later to be honest when people asked me about how he died. The answer “suicide” was not a conversation starter; the answer “car crash” was easier.

My father’s father never talked about it either. He lived thousands of miles away and only visited us in New York once. He lived the life of a recluse who seemed to still be in mourning over the loss of his only child. He symbolized walking sorrow.

When I turned 27, the same age that my father died by suicide, I was struck by how young I felt, full of hope and optimism for the future. I found it even harder to image how he arrived in his office early one morning, locked the door, sat at his desk and shot himself in the head.

After my grandmother died when I was in my 30s, I was helping to clear stuff out of the basement when the house was about to be listed on the real estate market. I found a stash of old letters that my father wrote to my mother because he traveled often, and they lived apart from time to time. The letters reflected waning optimism with every year and increasing themes of discontentment and disappointment yet no threats of taking his life. He did, however, provide a colorful description of where he wanted to be buried under magnolia trees in a specific cemetery.

The topic of suicide brings up many ifs — if only I had known he was so unhappy (said one of his childhood friends), and my mother told me many variations of if he were still alive. I really wish I had known him, and I always wanted to hear what his voice sounded like.

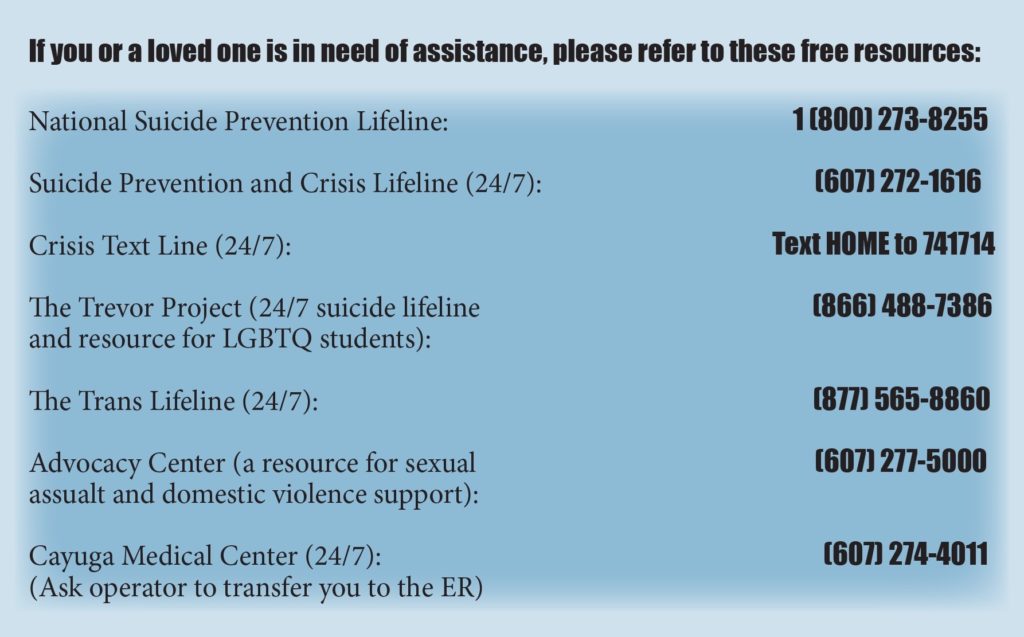

Suicide doesn’t only affect one person; it leaves a lifelong shadow over the immediate family, relatives and friends. The American Association of Suicidology states that approximately 1 million new people annually directly face losing someone by suicide, with a third of the survivors of suicide loss needing help or intervention. Other support services for survivors include the Alliance of Hope for Suicide Loss Survivors, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the Survivors of Suicide. If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, contact CAPS on campus or call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline available 24/7 at 800-273-8255 right away.