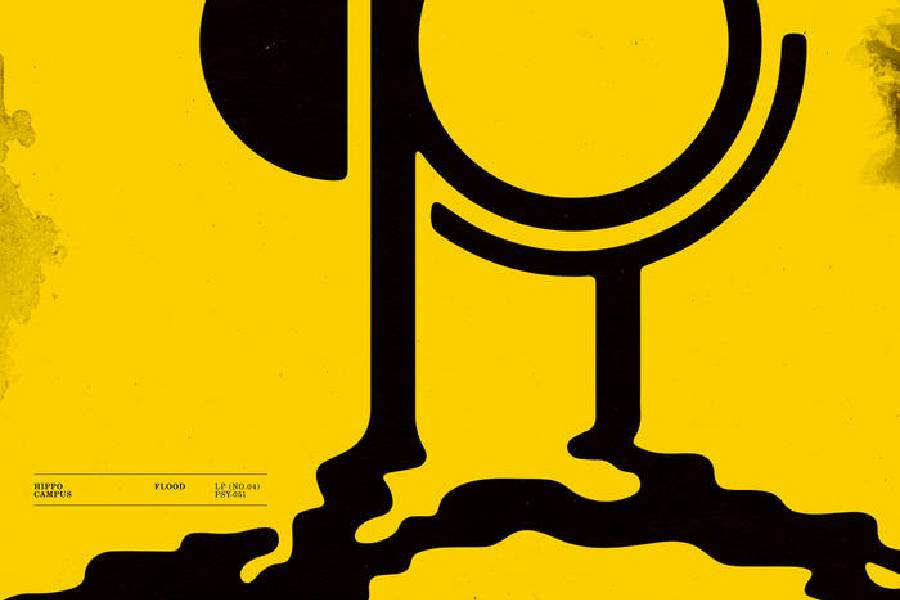

5.0 out of 5.0 stars

In “Manning Fireworks,” MJ Lenderman — an indie rock singer-songwriter most known for his distinct alt-country style — broke away from his folky, energetic strings. He tapped into a slower beat, letting his vocals carry him through nine well-composed tracks.

Although his gravelly voice was the most highlighted across the songs, Lenderman’s instrumentals were what made almost every song distinct. The album starts off strong with its title track, imitating a young Bob Dylan’s aching voice. The lyrics are pretty nonsensical, but as can be observed across the album, it is not about what is being said; it is about how it makes listeners feel.

“Joker Lips” is the only true ballad on the album, with heart-wrenching lyrics backed by a wistful guitar. Lenderman does not follow the typical verse-and-chorus format for any of his tracks on the record, letting repetitive instrumental melodies create the cohesive form of each song.

The latter portion of the album is more energetic than the first half, but “Rudolph” — the third track and one of the singles — is the exception. It is instrumentally upbeat and closer to the vibe of other indie alt songs. But it is clearly still Lenderman’s song, with deadpan singing and poetic lyricism as he longingly proclaims, “I wouldn’t be in the seminary if I could be with you.”

Of all the nonsensical lyrics on the album, “Wristwatch” was the hardest to comprehend. Yet it manages to emphasize the melancholy vibe of the album, reminding listeners that the words matter less than the feeling they evoke.

“She’s Leaving You” is most well-known, and his instrumentals are the catchiest so far, boasting hundreds of thousands more streams on Spotify than most other tracks, and for good reason. It is sung in the second person, but feels self-reflective because Lenderman seemingly tells himself, “It falls apart / we all got work to do / It gets dark / we all got work to do.” Unlike previous tracks, he does follow more of a typical song format for this. If it was not for the conflicting anger and defeat in his voice, the song could be considered pop.

With one final sad hurrah, “Rip Torn” is the tipping point for Lenderman’s dreamy depression. The guitar and vocals are reminiscent of past songs, but by throwing in some unique instrumentals in the background, Lenderman saves the song from becoming boring. The guitar solo is so beautiful it is almost disappointing when the vocals come in, but it is worth it for poetic lines like, “If you tap on the glass / The sharks might look at you / Damned if they don’t / And you’re damned if they do.”

If the spectrum of melancholy is paralyzing on the low end and motivating on the high end, the final three tracks are when Lenderman energizes the listener without completely ripping away the comfortable discomfort of the past six tracks.

“You Don’t Know The Shape I’m In” is transitionary, featuring hints of optimism in the background and conversational — rather than sing-songy — melodies sung by Lenderman. The groove is introduced and the next song, “On My Knees,” is the first time Lenderman inspires dancing rather than drowning. The kind of dancing the track encourages is not energetic, though, just dynamic and vibrant and — for the first time in nearly 30 minutes — the melancholy is motivating.

The lyrics are deceiving, with one line being, “And every day is a miracle” and the next being, “Not to mention a threat.” The drums hit harder and the guitar is more intense, even Lenderman’s voice springs to life. He keeps the lyrics ambiguous, and even the title carries different meanings: Is he begging? Praying? Expressing gratitude?

Lenderman rounds off the album with his best — and most direct — poetic lyricism yet in the lengthy “Bark At The Moon.” His voice dances smoothly with the swinging guitar and the reappearance of atypical instrumentals in the background bring reminders of the new wave genre, simplified. After spending so much of the album feeling weighed down, listeners can slip into a heart-lifting sweetness through lines like, “I could really use your two cents babe / I could really use the change.”

The first section of the track is essentially one song that lasts three and a half minutes, but with a sudden and striking dissonant chord, a whole new song begins. Purely instrumental, the next six and a half minutes of the finale are a series of discordant guitars and keyboards battling for air time. Lenderman exhibits angst contrasted by nostalgia, bringing back that thematic middle ground: melancholy. Although some parts are an assault on the ears, the whole concept is beautiful and raw. The track ends kindly as a soft synth fades out into the 10-minute mark.

Not only does Lenderman spend this new album shedding past personas, he challenges the standards of both pop and alternative music. In this melancholic masterpiece, he hints at longing and despair without ever needing to express those emotions verbally. He pulls listeners into a complex and emotional world and — with an aptly confusing send-off — pushes them back into the world with a few catchy chords stuck in their heads and a whole new feeling in their hearts.