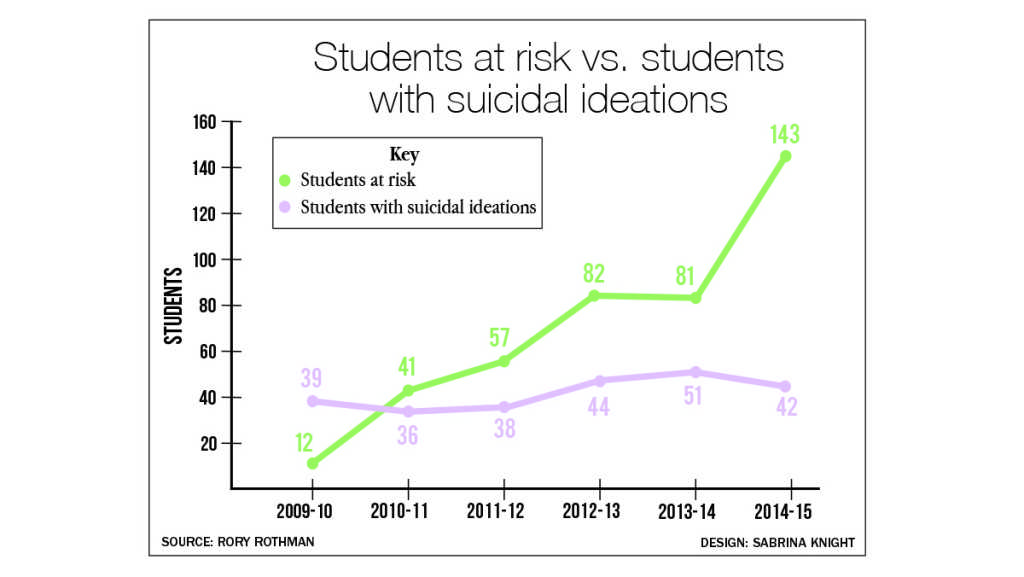

Ithaca College has seen a dramatic increase in the number of students who were reported to be “at risk” over the past five years.

Rory Rothman, associate provost for student life, said the college separates mental health cases into two groups: students at risk and students with suicidal ideations who pose an immediate danger to themselves. Students at risk show behavioral red flags such as absence from class or lack of motivation but don’t pose an immediate danger to themselves or others.

The number of cases of students with suicidal ideations has remained relatively steady over the past five years, with an average of about 42 cases per year. The number of students at risk, however, increased from 12 in the 2009–10 school year to 143 in the 2014–15 school year, a 1,092 percent increase.

Christina McMahon, student case manager at the college, is the head of iCare, which was rolled out in Fall 2015 to handle the increase in cases of students at risk. McMahon said iCare is made up of representatives from different areas on campus — the Office of Residential Life, the Hammond Health Center and all constituent offices, the Office of Public Safety and Emergency Management and the Academic Advising Center — who meet weekly to discuss cases and specific action needed for particular students. Rothman said the student case manager position was added to the Office of Student Affairs and Campus Life in January 2015 as a direct response to an increase in cases of students at risk.

ICare is not an emergency response system. Public Safety is the first line of contact for a student in a crisis situation, McMahon said. Instead, the iCare team handles cases that may have been given to them by Public Safety, a concerned friend, a parent, a professor or the student in question.

The week of Sept. 28–Oct. 5 yielded six mental health–related reports, including both Public Safety welfare checks and medical assistances due to potential or actual self-endangerment. Two of the people who were reported were taken into custody and transported to the hospital. The months of August and September had one and 10 reports in total, respectively.

Rothman said the increase in numbers does not necessarily mean the number of students at risk has increased — rather, reporting has. Rothman said the college follows a national trend in increased behavioral reporting and case management.

According to the Center for Collegiate Mental Health’s annual report in 2014, 70 universities and colleges across the country reported that, cumulatively, 12,010 case-management appointments were attended by students. Comparatively, the CCMH’s 2013 annual study showed that only 7,618 case–management appointments were filled. The 2013 CCMH study was the first report where case-management data was provided. During a case-management appointment, McMahon said she and the student would discuss the student’s situation and diagnose the best possible resources for that student’s future success.

McMahon said school shootings, like the one at Virginia Tech in 2007, showed everyone that mental health was something that had to be dealt with before it reached a crisis situation.

McMahon helps students navigate academic pressures, personal issues and physical and mental health problems, while also providing personal success strategies for the student.

“I’m not a therapist,” McMahon said. “Sometimes I’m providing case–management support to students that aren’t reaching the level of a crisis, but they could still utilize me as someone to talk to them to keep them out of that statistic.”

Rothman said the increase in cases has been a challenge for McMahon and her office, but they haven’t seen any backlogs or significant wait times.

Public Safety officers receive mental health education as part of their training at the New York State Police Academy in addition to a six-month training at the college that includes mental health and crisis response, said Bill Kerry, lieutenant in the Office of Public Safety.

Public Safety will investigate any evidence of a student in danger, no matter how small, Kerry said. Welfare checks usually hinge on conversations the officer has with the student at risk or others who are involved. Officers will use their training to deem if the student in question is a harm to themselves or others, Kerry said.

If the officer believes the student is an immediate danger to themselves or others, then the student will be taken into custody. If the student is deemed to be fine, then a report will be drafted and follow-up care administered. In both circumstances a report is given to the iCare team.

The college will not punish a student after being taken into custody for suicidal ideations, said Mike Leary, assistant director for the Office of Judicial Affairs. The policy was starkly different from the policy two years ago that punished students after hospitalization, he said.

“The old policy was outdated and didn’t reflect the values of the college,” he said. “Our main goal is the health and safety of the student body.”

Junior Natalie Grande, a former resident assistant, said she and her fellow RAs were trained to use the iCare system and were encouraged to report concerning behaviors to their residence director. However, Grande said she has never needed to fill out an iCare report.

“They really promoted the iCare system, early identification and really how to have conversations with the student,” Grande said.

Grande said the trainings she received prepared her for behavioral intervention and crisis situations.

McMahon said the program’s ultimate goal is to help students.

“Whatever we can do to alleviate that student’s pressure,” McMahon said, “that’s our goal.”