There is power in the collective,” POC at IC posted on Facebook after President Tom Rochon announced Jan. 14 that he would step down July 1, 2017. “We did it!”

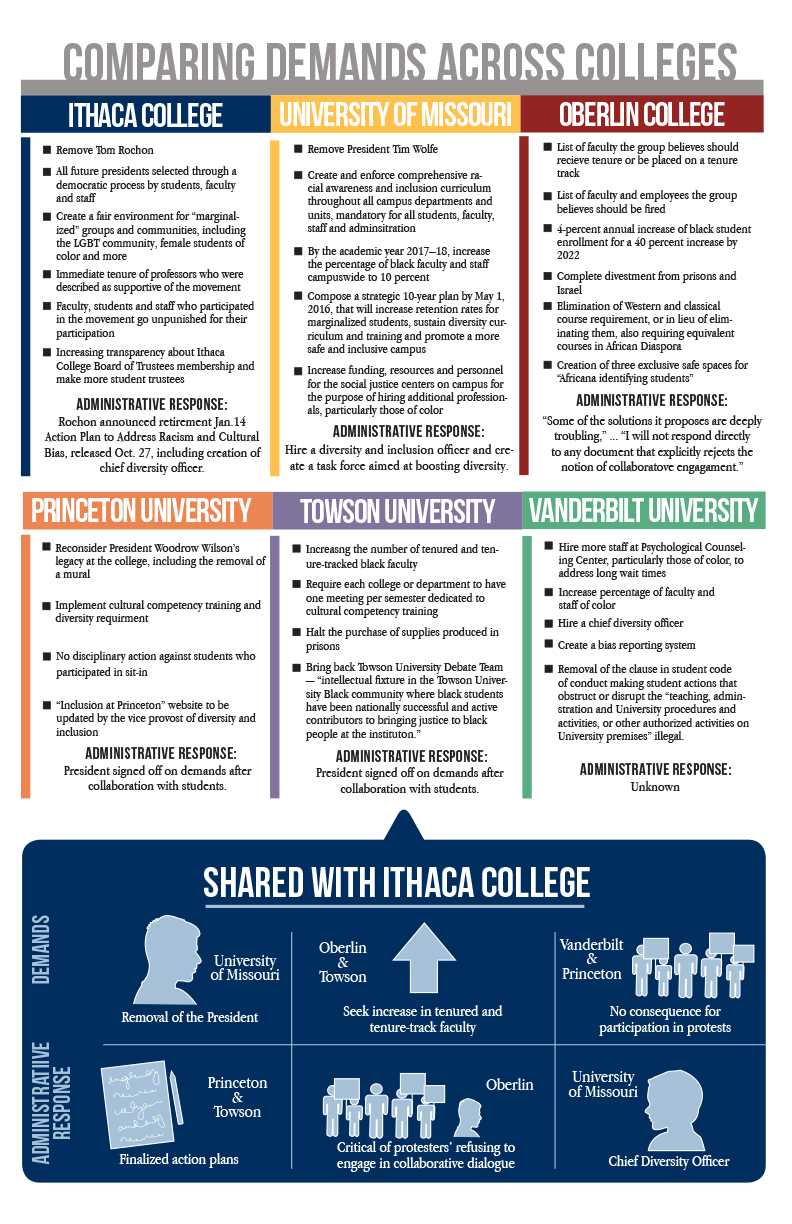

Students protesting the racial climate at Ithaca College are not the only ones finding a collective voice with which to address institutionalized racism. In a tumultuous fall semester, at least 75 other colleges and universities have begun bringing their demands for change to their administrations.

While every campus has a unique approach to initiating change, the overall message is clear: Campus communities believe long-standing, underlying racial tensions cannot be swept under the rug anymore.

Issues and Demands

While students of color at several colleges said racial and diversity issues are nothing new, there were specific events in the fall that triggered their student activism.

Concerned Student 1950, the University of Missouri’s student protest group, formed after numerous racial incidents in the fall: Payton Head, the president of the Missouri Students Association, posted on Facebook that racial slurs had been yelled at him; a student group was preparing for the Homecoming Parade when a white man called them the N-word; and when students confronted President Tim Wolfe at the parade, he didn’t acknowledge them, leading to accusations that he was dismissive.

People of Color at Ithaca College emerged in October, citing a history of racist events at the college and longstanding issues with microaggressions both inside and outside the classroom. Insensitive comments made by Public Safety officers to resident assistants, the planning of a racially themed party by off-campus fraternity Alpha Epsilon Pi, and racial remarks made by alumni at the Blue Sky Reimagining Kick-Off event Oct. 8 all catalyzed the group’s protests.

In early November at Claremont McKenna College in Southern California, students were upset over an email from Mary Spellman, dean of student affairs, to a Latina student, saying she would work to serve those who “don’t fit our CMC mold.” A woman of color at Claremont McKenna, Casey Garcelon, also posted a photo of students wearing culturally insensitive Halloween costumes on Facebook. Garcelon said these events were part of an underlying institutional issue.

“It’s not something that’s new, and I think that’s what people forget. It’s a history,” Garcelon said. “I think there is a lot of institutional amnesia in the cycle of [students] coming in and moving out.”

In mid-November at Yale University in Connecticut, protests began after allegations that a fraternity held a “white girls only” party. Additionally, a Yale lecturer, Erika Christakis, responded to student concern over racially insensitive costumes by writing in an email: “Is there no room anymore for a child or young person to be … a little bit inappropriate or provocative or, yes, offensive?” according to Time Magazine.

Kendra Farrakhan, a student at Oberlin College in Ohio, said students of color began organizing after a string of events in 2013 in which racial slurs and swastikas were posted around campus. Farrakhan said she does not feel Oberlin’s administration addressed these events adequately. In the fall, Farrakhan and other members of Abusua, a black student organization, created a 14-page document laying out 58 demands that was given to the administration.

The demands include a 4 percent annual increase of black student enrollment; the elimination of Western and classical course requirements, or also requiring equivalent courses in African Diaspora; the creation of three safe spaces for “Africana identifying students”; and a list of faculty to receive tenure or be placed on a tenure track.

Missouri protesters, in a list released in October, demanded an increase in the percentage of black faculty and staff campuswide to 10 percent by the 2017–18 academic year. Rebekah Hurley, a Missouri student, said having more faculty of color would positively benefit her college experience.

“I can say from a personal standpoint that when I’m going through something particularly difficult in my life … it’s often easier for me to speak to somebody that almost looks like me,” Hurley said.

Tenuring faculty of color and increasing diversity at colleges is a common demand among protest movements. At the Nov. 11 Ithaca College walk-out event, members of POC at IC introduced the group’s demands.

In addition to tenuring faculty members who were supportive of the movement, the demands included allowing all future presidents to be selected through a democratic process by all constituencies; creating a fair environment for “marginalized” groups and communities of all kinds; that no one be punished for participation in the movement; and increasing transparency with Ithaca College Board of Trustees membership while appointing more student trustees.

Activist Strategies

In response to these events and continuing underlying grievances with campus climates, students have united into groups and used a

combination of sit-ins, walk-outs, hunger strikes and boycotts to make themselves heard.

Missouri was the first in the nationwide sweep of college protests to attract national media attention. The combination of a weeklong hunger strike, a student encampment on a quad and refusal from the football team to play resulted in national attention.

Students at Oberlin, like those at Ithaca College, were not interested in discussions with administration. Protesters claimed their demands were non-negotiable and said there would be “a full and forceful response” if they were not met.

From early on, members of POC at IC were clear they had little interest in discussions. At the group’s first major protest Oct. 21, participants chanted, “No more dialogue: We want action!”

In addition to their stance against “empty dialogue” with administration, POC at IC also held large-scale protests and rallies, including demonstrations during the Oct. 24 Fall Open House, seizing the Athletics and Events Center stage from Rochon at an Oct. 27 forum and holding a “die-in” protest Nov. 11 that drew approximately 1,000 participants.

Keisha Bentley-Edwards, an assistant professor in the Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Texas at Austin, focuses on the racial experiences of youth and the outcomes of racism stress and aggression on youth in the black community. Responding to the widespread protests here at the college and across the country, Bentley-Edwards said a community dynamic often defines the protests that will be successful

from those that tend to fade away.

She also said pressure from faculty advocating for students can be influential in a leadersstepping down.

“I think that a big thing is communicating, having the smaller conversations,” Bentley-Edwards said. “So at Missouri, you had graduate students, athletes as well as the faculty, coaches and alumni. At Ithaca College, you had faculty recognizing the issues and being active in the college community. … You talk about what your concerns are and what can be done.”

Unlike POC at IC, students at Towson University in Maryland stayed open to discussion of their grievances with administrators.

According to a statement from Timothy Chandler, interim president of Towson, students arrived Nov. 18 at the president’s office to present their concerns and a list of demands, and together they reworked the document for nearly 10 hours.

A different approach was used at Claremont McKenna College. Along with the photo of perceived culturally appropriative Halloween costumes posted to Facebook, Garcelon wrote: “For anyone who ever tries to invalidate the experiences of POC at the Claremont Colleges, here is a reminder of why we feel the way we do. … If you feel uncomfortable by my cover photo, I want you to know I feel uncomfortable as a person of color everyday on this campus.”

Garcelon said media attention was a key factor in putting pressure on the administration to meet their demands.

Bentley-Edwards said social media and the media’s spotlighting these protests in general have helped students connect and define their shared experiences and have even resulted in sharing aspects of protests that other schools can employ in their own demonstrations.

“Media … influences whether or not students feel isolated as they realize that this is a culture not only at their university, but other schools that are accessible,” she said. “They learn from each other and share experiences that define them, as well as sharing strategies that are also happening in real time.”

Outcomes

To date, the resignation of top administrators has occurred at three schools: the University of Missouri, Claremont McKenna College and Ithaca College.

At Missouri, Wolfe stepped down Nov. 9 under the pressure of the student’s hunger strike and the football team’s refusal to play. At Claremont McKenna, Spellman resigned Nov. 12 following student protests over her “CMC mold” comment. Rochon said Jan. 14 he would retire early, effective July 2017, having reflected on the events of the fall semester over winter break.

Hurley said she thinks the campus climate has improved since Wolfe stepped down.

“I would say it made me feel closer, not just to the black community, but students as a whole,” Hurley said. “I have a lot of friends that aren’t students of color that have wanted to be more educated on the topic.”

Despite only three schools experiencing a change of leadership, Sean McKinniss, a graduate from the Ph.D. program in Higher Education and Student Affairs at Ohio State University, said student protests result in changes in leadership most of the time, although they may not be the immediate effect protestors often call for.

McKinniss is the creator of some of the most comprehensive research and a database compiled on no confidence votes against leaders in higher education. Out of the 138 cases he has studied, a pattern has emerged regarding the length leaders stay in their office following votes and protests.

“Usually presidents leave, and that could be anywhere from a few days up to a few years … because when you lose the support of your key constituency, it just creates a really nasty culture and environment on your campus,” McKinniss said.

Although Yale students did not call for the resignation of their president, other demands are being met. Following student protests, Yale President Peter Salovey announced plans for the creation of an academic center focused on race, ethnicity and social identity, in addition to four new positions for scholars working in those fields. Salovey also pledged to increase resources for existing centers serving students of color, and he also said top administrators would undergo training to intervene in racism or discriminatory behavior, according to The New York Times.

At Towson University and Princeton University, students collaborated with administrative officials on demands resulting in their president’s signing documents that both parties agreed on.

The final document at Towson featured 12 requests, 11 of which would be implemented by Fall 2016. They include increasing the number of tenured and tenure-tracked black faculty and requiring each college or department to have one meeting per semester dedicated to cultural competency training. Chandler signed off on the document, agreeing to resign if unable to meet the requests.

“The resulting final document was a list of commitments that are completely aligned with Towson University’s core values,” Chandler said in the statement. “We feel confident that we can move forward with the list of commitments.”

A demand unique to Princeton that was written into the final agreement signed by President Christopher Eisgruber was the decision to review President Woodrow Wilson’s legacy at the university. Wilson was the president of Princeton from 1902–10. During his time in the Oval Office, Wilson resegregated federal agencies and expressed his support for the Ku Klux Klan. Princeton student activists hope to replace Wilson’s mural with “greater ethnic diversity of memorialized artwork on campus.”

As for students at Oberlin, who asserted that their demands were non-negotiable, Oberlin’s president, Marvin Krislov, said in a response Jan. 20 that while he “resonates with” some of the challenges outlined in the document, “some of the solutions it proposes are deeply troubling.”

“I will not respond directly to any document that explicitly rejects the notion of collaborative engagement,” Krislov said. “Many of its demands contravene principles of shared governance. And it contains personal attacks on a number of faculty and staff members who are dedicated and valued members of this community.”

Farrakhan said due to a lack of support from Oberlin and the uncomfortable campus climate, she would not be returning for the spring semester.

“It’s really disheartening. … Every single year I watch freshmen come in who were so excited to be here, who were so excited about Oberlin’s reputation of being a progressive institution and being concerned with social justice and … everything that they put in the brochures, and to find out that that is just a marketing scheme — it’s not reflected in the values of the day-to-day operations,” she said.

In response to initial POC at IC protests, the college released a plan Oct. 27 with proposed actions to address racism and cultural bias before the activist group had formally announced demands. According to the action plan, an outside firm, Rankin and Associates Consulting, will develop a campus-climate survey this spring, and the survey will be administered in Fall 2016. A retention program for African, Latino, Asian and Native American faculty will be developed, and an independent external review of the Office of Public Safety and Emergency Management will be conducted, both during the spring.

The plan also calls for an increase in enrollment of ALANA and international students. Beginning in February, all new college employees will be required to participate in a cross-cultural awareness training program within three months of being hired. Employees hired prior to February will have until May to complete the training.

According to a Jan. 14 statement from Tom Grape, chair of the board of trustees, the search process for Rochon’s replacement will include input from students, faculty, staff and alumni. However, the board of trustees will still maintain ultimate deciding power, contrary to POC at IC’s demand that the president be elected democratically.

Nothing has been announced in response to the demand for increased transparency with the board of trustees or granting tenure to specific faculty members.

Roger Richardson, interim chief diversity officer and associate provost of diversity, inclusion and engagement, announced updates to the college’s action plan Jan. 26. According to the announcement, a “safe space” for students of color will become functional in Fall 2016; faculty search committee chairs have completed training on new hiring guidelines surrounding inclusivity; the workgroup responsible for creating a review board to report concerns regarding Public Safety has completed research on best practices; and the Office of Human Resources has developed a series of cross-cultural awareness workshops for the college community.

Clara Ma, a freshman at Yale, said media portrayal of the events across the country can make the movement seem polarized with “vastly different sides who want very different things.”

“But, honestly, I feel like in the most basic sense, we all want pretty similar things … to understand one another — to foster an environment that is both intellectual and inclusive,” Ma said.